Table of Contents

Chapter 5

Association POW Diplomacy Extends to Eastern and Southern Europe

1

While Archibald Harte and Carlisle Hibbard conducted negotiations in the West, the World's Alliance of YMCAs had

already begun providing relief in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Christian Phildius traveled to Vienna and began

negotiations with the Dual Monarchy government to establish relief work for soldiers as a pre-condition for

welfare work for POWs held by the Austro-Hungarians. More importantly, by May 1915, Harte faced a dilemma in

Germany. The German government recognized that the YMCA was providing important welfare relief for German

prisoners in Britain and France, and that Western Allied POWs received similar treatment in German prisons.

Because the Germans integrated the Allied POWs in their prisons, Russian and Serbian prisoners received welfare

benefits in German prisons that German prisoners did not yet receive in Russia and Serbia. To expand operations

in Germany, the YMCA had to gain access to Central Power prisoners held in Eastern Europe. Harte also recognized

that, for the Russians to accept American YMCA POW services, the Association would have to extend its operations

to Austria-Hungary, which held a large number of Russian prisoners. This intricate web of diplomacy was further

complicated by Italy's entry into the war in May 1915. Association services to POWs in Austria-Hungary would

include Italian prisoners, and the Dual Monarchy would demand reciprocity for Austro-Hungarian prisoners in Italy.

Bulgaria's entry into the war in October 1915, followed by Romania's war declaration in August 1916, compounded

the terrible conditions prisoners faced. To expand operations and meet the needs of war prisoners, Association

secretaries would have to persuade the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Serbian, Italian, Bulgarian, and Romanian

governments to accept YMCA services.

While Archibald Harte and Carlisle Hibbard conducted negotiations in the West, the World's Alliance of YMCAs had

already begun providing relief in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Christian Phildius traveled to Vienna and began

negotiations with the Dual Monarchy government to establish relief work for soldiers as a pre-condition for

welfare work for POWs held by the Austro-Hungarians. More importantly, by May 1915, Harte faced a dilemma in

Germany. The German government recognized that the YMCA was providing important welfare relief for German

prisoners in Britain and France, and that Western Allied POWs received similar treatment in German prisons.

Because the Germans integrated the Allied POWs in their prisons, Russian and Serbian prisoners received welfare

benefits in German prisons that German prisoners did not yet receive in Russia and Serbia. To expand operations

in Germany, the YMCA had to gain access to Central Power prisoners held in Eastern Europe. Harte also recognized

that, for the Russians to accept American YMCA POW services, the Association would have to extend its operations

to Austria-Hungary, which held a large number of Russian prisoners. This intricate web of diplomacy was further

complicated by Italy's entry into the war in May 1915. Association services to POWs in Austria-Hungary would

include Italian prisoners, and the Dual Monarchy would demand reciprocity for Austro-Hungarian prisoners in Italy.

Bulgaria's entry into the war in October 1915, followed by Romania's war declaration in August 1916, compounded

the terrible conditions prisoners faced. To expand operations and meet the needs of war prisoners, Association

secretaries would have to persuade the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Serbian, Italian, Bulgarian, and Romanian

governments to accept YMCA services.

Austro-Hungarian YMCA War Work Service

2

When the Habsburg government declared war against Serbia on 28 July 1914, the Austro-Hungarian YMCA sprang

into action to meet the wartime emergency. The National Union of Austro-Hungarian Associations was successful

in supporting the war effort. At the beginning of the war, the National YMCA was severely limited in both

membership and financial resources. Its initial goal was restricted to assisting Protestant soldiers and recently

drafted students. With the financial support of the American YMCA and the personnel assistance of the World's

Alliance, the National Union expanded their operations across the empire by providing services to soldiers in

major military camps and ministering to sick and wounded soldiers. Starting with one Soldatenheim in October

1914, the National Union established Soldiers' Homes in eleven Austrian cities and twelve Hungarian cities by

October 1916, establishing a truly national and ecumenical work. Secretaries proved that they could offer

entertainment, mental diversions, and religious comforts to soldiers from all parts of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire, and to both Protestant and Catholic troops. The National Union helped to set up a social welfare system

for the Austro-Hungarian military, which the imperial government lacked the resources and expertise to

establish.1

When the Habsburg government declared war against Serbia on 28 July 1914, the Austro-Hungarian YMCA sprang

into action to meet the wartime emergency. The National Union of Austro-Hungarian Associations was successful

in supporting the war effort. At the beginning of the war, the National YMCA was severely limited in both

membership and financial resources. Its initial goal was restricted to assisting Protestant soldiers and recently

drafted students. With the financial support of the American YMCA and the personnel assistance of the World's

Alliance, the National Union expanded their operations across the empire by providing services to soldiers in

major military camps and ministering to sick and wounded soldiers. Starting with one Soldatenheim in October

1914, the National Union established Soldiers' Homes in eleven Austrian cities and twelve Hungarian cities by

October 1916, establishing a truly national and ecumenical work. Secretaries proved that they could offer

entertainment, mental diversions, and religious comforts to soldiers from all parts of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire, and to both Protestant and Catholic troops. The National Union helped to set up a social welfare system

for the Austro-Hungarian military, which the imperial government lacked the resources and expertise to

establish.1

3

The National Union faced serious obstacles that hindered its effectiveness. Austro-Hungarian secretaries were

not permitted to administer relief to soldiers at the front-work had to be undertaken through correspondence

or in the rear areas. Secretaries also had to communicate with soldiers that spoke twelve different languages,

which limited the programs they could offer. These restrictions further complicated the delivery of YMCA

relief services. The government never provided the YMCA with postage franking privileges, which greatly

increased Association costs. The American, British, French, Russian, Italian, and German governments extended

this privilege to Associations operating within their borders. The National Union in the Habsburg Empire

simply lacked the resources to expand its operations. While the National Association did receive some gifts

from wealthy subjects, it relied heavily on foreign aid from the U.S. and Switzerland. The Austro-Hungarian

economy was shattered by the war, and this had a terrible impact on the subjects of the empire. The Association's

limitations may have been due to the underdeveloped status of the Austro-Hungarian YMCA before the war broke out,

which prevented it from taking a more active role in the war effort. It is also possible that its Protestant

origins made it generally suspect to the Catholic Dual Monarchy military authorities. There are many reports of

Catholic distrust of the YMCA's intentions. The Roman Catholic clergy looked on this social work with suspicion,

and occasionally instructed Catholic troops not to visit the Vienna Soldatenheim. One countess spent a

considerable amount of time trying to catch Association secretaries attempting to proselytize soldiers. Despite

her efforts, she could not obtain any proof, and learned that secretaries were simply trying "to do good and

bring each man in his own religion to the highest possible development." Even the Bishop of Vienna investigated

the Association headquarters to find out the true nature of YMCA work and determine whether the secretaries were

involved in sectarian propaganda. After listening to a thirty-minute presentation, he declared, "God bless you

and your work. The good you are doing is the best preparation for peace."2

The National Union faced serious obstacles that hindered its effectiveness. Austro-Hungarian secretaries were

not permitted to administer relief to soldiers at the front-work had to be undertaken through correspondence

or in the rear areas. Secretaries also had to communicate with soldiers that spoke twelve different languages,

which limited the programs they could offer. These restrictions further complicated the delivery of YMCA

relief services. The government never provided the YMCA with postage franking privileges, which greatly

increased Association costs. The American, British, French, Russian, Italian, and German governments extended

this privilege to Associations operating within their borders. The National Union in the Habsburg Empire

simply lacked the resources to expand its operations. While the National Association did receive some gifts

from wealthy subjects, it relied heavily on foreign aid from the U.S. and Switzerland. The Austro-Hungarian

economy was shattered by the war, and this had a terrible impact on the subjects of the empire. The Association's

limitations may have been due to the underdeveloped status of the Austro-Hungarian YMCA before the war broke out,

which prevented it from taking a more active role in the war effort. It is also possible that its Protestant

origins made it generally suspect to the Catholic Dual Monarchy military authorities. There are many reports of

Catholic distrust of the YMCA's intentions. The Roman Catholic clergy looked on this social work with suspicion,

and occasionally instructed Catholic troops not to visit the Vienna Soldatenheim. One countess spent a

considerable amount of time trying to catch Association secretaries attempting to proselytize soldiers. Despite

her efforts, she could not obtain any proof, and learned that secretaries were simply trying "to do good and

bring each man in his own religion to the highest possible development." Even the Bishop of Vienna investigated

the Association headquarters to find out the true nature of YMCA work and determine whether the secretaries were

involved in sectarian propaganda. After listening to a thirty-minute presentation, he declared, "God bless you

and your work. The good you are doing is the best preparation for peace."2

World's Alliance POW Diplomacy in the Dual Monarchy

4

When the war began, Christian Phildius started efforts in the Austrian Association to extend YMCA work to

POWs in the Dual Monarchy. At first, Austro-Hungarian military authorities did not permit personal work

among Russian and Serbian prisoners. The only service they did allow was the distribution of religious

literature through Austro-Hungarian Red Cross channels. Unfortunately, the National Alliance had only a

limited supply of Holy Scriptures in Russian and Serbian but they augmented their supplies the help of

the British and Foreign Bible Society and a Swiss donor. By March 1915, over two hundred thousand Russian and Serbian

POW's were held in the Dual Monarchy and many were eager to get their hands on anything they could read.

Secretaries considered this a unique opportunity to place copies of the Gospel into the hands of men who

now had the time to read, study, and meditate. Phildius wrote to the International Committee in New York,

"Should we not use this God-given opportunity without delay, as most of these poor men may never have read

the Gospel story in their own language and, when once returned to their country, may never hear it again."

By April 1915, the Austrian YMCA distributed Gospels to twenty-seven thousand Russian and Serbian POWs through the

Austro-Hungarian Red Cross. Phildius made contacts with other Bible societies, including the American Bible

Society and British and Foreign Bible Society, to ensure continued deliveries of Gospels to war prisoners,

but lamented that this was the only welfare service the Austro-Hungarian Association could offer. He hoped

to persuade the imperial authorities to let the YMCA extend regular services to POWs to help ease their

suffering.3

When the war began, Christian Phildius started efforts in the Austrian Association to extend YMCA work to

POWs in the Dual Monarchy. At first, Austro-Hungarian military authorities did not permit personal work

among Russian and Serbian prisoners. The only service they did allow was the distribution of religious

literature through Austro-Hungarian Red Cross channels. Unfortunately, the National Alliance had only a

limited supply of Holy Scriptures in Russian and Serbian but they augmented their supplies the help of

the British and Foreign Bible Society and a Swiss donor. By March 1915, over two hundred thousand Russian and Serbian

POW's were held in the Dual Monarchy and many were eager to get their hands on anything they could read.

Secretaries considered this a unique opportunity to place copies of the Gospel into the hands of men who

now had the time to read, study, and meditate. Phildius wrote to the International Committee in New York,

"Should we not use this God-given opportunity without delay, as most of these poor men may never have read

the Gospel story in their own language and, when once returned to their country, may never hear it again."

By April 1915, the Austrian YMCA distributed Gospels to twenty-seven thousand Russian and Serbian POWs through the

Austro-Hungarian Red Cross. Phildius made contacts with other Bible societies, including the American Bible

Society and British and Foreign Bible Society, to ensure continued deliveries of Gospels to war prisoners,

but lamented that this was the only welfare service the Austro-Hungarian Association could offer. He hoped

to persuade the imperial authorities to let the YMCA extend regular services to POWs to help ease their

suffering.3

5

In the Dual Monarchy, Phildius gained some support from the Austro-Hungarian government. With the aid of

Frederic C. Penfield, the U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, Phildius persuaded the Austro-Hungarian War

Office to permit Austrian secretaries to begin services at two prison camps. The German government had

decided to permit American secretaries to begin work in prison camps in Germany, and the Austro-Hungarians

were impressed with the American service. The Minister of War instructed Lieutenant Field Marshal Urban to

inform Ambassador Penfield on 27 May 1915:

In the Dual Monarchy, Phildius gained some support from the Austro-Hungarian government. With the aid of

Frederic C. Penfield, the U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, Phildius persuaded the Austro-Hungarian War

Office to permit Austrian secretaries to begin services at two prison camps. The German government had

decided to permit American secretaries to begin work in prison camps in Germany, and the Austro-Hungarians

were impressed with the American service. The Minister of War instructed Lieutenant Field Marshal Urban to

inform Ambassador Penfield on 27 May 1915:

…that it will grant the Young Men's Christian Association permission for the present to carry on its work of humanity in one prisoners' camp each in Austria and in Hungary. Whether an extension of the charitable activities of the World's Union [World's Alliance] to other prisoners' camps can be given consideration will depend upon the results attained and upon the analogous action on the part of the Imperial Russian and Royal Serbian governments.

The imperial government selected Braunau-in-Böhmen in Bohemia and Sopronnyek in Hungary, each with thirty thousand Russian POWs, as the first sites for Association work. Under this permit, the Ministry of War granted the YMCA permission to construct a hut and assign one secretary in each camp.4

6

The Austro-Hungarian government was impressed with the results the American YMCA had achieved in Germany, and

saw potential benefit for Dual Monarchy prisoners in Allied war prisons. When the government granted the

Association permission to begin work in Austria-Hungary in May 1915, Sir Alarad von Szilassy indicated it

could be expanded to other POW camps, including Brünn in Moravia, Prague in Bohemia, Kenyermezö in

Hungary, and Spratzern and Wieselburg in Lower Austria by the end of the year. The key to greater access to

Austro-Hungarian prisons lay in "reciprocity diplomacy." Viennese officials insisted that their nationals

languishing in Russian and Serbian prison camps must also receive YMCA POW services.5

The Austro-Hungarian government was impressed with the results the American YMCA had achieved in Germany, and

saw potential benefit for Dual Monarchy prisoners in Allied war prisons. When the government granted the

Association permission to begin work in Austria-Hungary in May 1915, Sir Alarad von Szilassy indicated it

could be expanded to other POW camps, including Brünn in Moravia, Prague in Bohemia, Kenyermezö in

Hungary, and Spratzern and Wieselburg in Lower Austria by the end of the year. The key to greater access to

Austro-Hungarian prisons lay in "reciprocity diplomacy." Viennese officials insisted that their nationals

languishing in Russian and Serbian prison camps must also receive YMCA POW services.5

Harte and Reciprocity with Russia

7

Although Harte and Hibbard had focused their attention on gaining access to prison camps in Western Europe,

by early May 1915 Harte had concluded that further expansion in Germany was impossible without reciprocal

access to German POWs in Russia. The American secretary received requests for Association work and YMCA huts

from many camps, and the WPA committee proposed several new projects. The German Ministry of War was unwilling

to authorize any expansion in services without similar relief for German POWs, especially in Russia. Many

Germans were concerned about the welfare of their countrymen in the East, especially as reports spread about

the inhumane conditions in the Siberian camps. U.S. Ambassador James W. Gerard strongly supported the extension

of American Red Triangle services to the Tsar's domain, and Harte agreed that successful access to Russian

prisons would give the Association a freer hand in Germany. As a result, Harte prepared for a trip to Petrograd

to meet with Russian authorities about opening Eastern prison camps to the American YMCA.6

Although Harte and Hibbard had focused their attention on gaining access to prison camps in Western Europe,

by early May 1915 Harte had concluded that further expansion in Germany was impossible without reciprocal

access to German POWs in Russia. The American secretary received requests for Association work and YMCA huts

from many camps, and the WPA committee proposed several new projects. The German Ministry of War was unwilling

to authorize any expansion in services without similar relief for German POWs, especially in Russia. Many

Germans were concerned about the welfare of their countrymen in the East, especially as reports spread about

the inhumane conditions in the Siberian camps. U.S. Ambassador James W. Gerard strongly supported the extension

of American Red Triangle services to the Tsar's domain, and Harte agreed that successful access to Russian

prisons would give the Association a freer hand in Germany. As a result, Harte prepared for a trip to Petrograd

to meet with Russian authorities about opening Eastern prison camps to the American YMCA.6

8

Harte departed for Petrograd on 18 May 1915. Before the war, the American YMCA had focused on developing an

Association movement in Russia as part of Mott's plan to expand into the Orthodox world. Through the financial

generosity of James Stokes, a wealthy American philanthropist who in 1886 supported the establishment of the

YMCA in Paris, the Association began its nascent work in Russia. The Russian Association movement began

in St. Petersburg in 1900, and was known as the Miyak (Lighthouse). Work in the Russian Empire grew

slowly, so that, by July 1914, the Miyak had made only minimal gains. In addition to the Petrograd

Association, the Russian YMCA was building a facility in Moscow and had permission to start a third

organization in Kiev. Two major obstacles hindered YMCA growth in the Tsarist empire. First, Russia was

intensely Orthodox and, ever fearful of proselytizing, they were suspicious of Protestant welfare agencies

operating within their borders. Second, the Russians tended towards xenophobia, and they remained on guard

against any foreign organizations. This xenophobia was further fanned by Pan-Slavic nationalism, which erupted

across the country in response to the war against the Central Powers.7

Harte departed for Petrograd on 18 May 1915. Before the war, the American YMCA had focused on developing an

Association movement in Russia as part of Mott's plan to expand into the Orthodox world. Through the financial

generosity of James Stokes, a wealthy American philanthropist who in 1886 supported the establishment of the

YMCA in Paris, the Association began its nascent work in Russia. The Russian Association movement began

in St. Petersburg in 1900, and was known as the Miyak (Lighthouse). Work in the Russian Empire grew

slowly, so that, by July 1914, the Miyak had made only minimal gains. In addition to the Petrograd

Association, the Russian YMCA was building a facility in Moscow and had permission to start a third

organization in Kiev. Two major obstacles hindered YMCA growth in the Tsarist empire. First, Russia was

intensely Orthodox and, ever fearful of proselytizing, they were suspicious of Protestant welfare agencies

operating within their borders. Second, the Russians tended towards xenophobia, and they remained on guard

against any foreign organizations. This xenophobia was further fanned by Pan-Slavic nationalism, which erupted

across the country in response to the war against the Central Powers.7

9

Despite these tensions, Harte pressed ahead with his mission. For two weeks, the American secretary met with

leading Russian dignitaries, including the Procurator of the Holy Synod, Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna,

General Beliaeff (Chief of the General Staff), and numerous Foreign Ministry officials.

Despite these tensions, Harte pressed ahead with his mission. For two weeks, the American secretary met with

leading Russian dignitaries, including the Procurator of the Holy Synod, Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna,

General Beliaeff (Chief of the General Staff), and numerous Foreign Ministry officials.

The U.S. Ambassador to Petrograd, George Thomas Marye, supported the YMCA representative. The American

embassy in Petrograd was overwhelmed by German and Austro-Hungarian POW work, which represented eighty

percent of the staff's total activity. Harte was armed with photographs, motion pictures, and reports

regarding the treatment of Russian POWs in Germany and the Association's efforts in improving their condition.

When Harte finally gained an audience with Tsarina Alexandra, she was impressed with his presentation.

The U.S. Ambassador to Petrograd, George Thomas Marye, supported the YMCA representative. The American

embassy in Petrograd was overwhelmed by German and Austro-Hungarian POW work, which represented eighty

percent of the staff's total activity. Harte was armed with photographs, motion pictures, and reports

regarding the treatment of Russian POWs in Germany and the Association's efforts in improving their condition.

When Harte finally gained an audience with Tsarina Alexandra, she was impressed with his presentation.

In early June 1915, Harte and George M. Day, an American YMCA secretary working with the Miyak, received

official permission to visit prison camps in Siberia. During this trip, Harte practiced the same tactics he

had used to secure the confidence of German Ministry of War officials. Conditions in Russia and Siberia were

as bad as reported by the German press.

In early June 1915, Harte and George M. Day, an American YMCA secretary working with the Miyak, received

official permission to visit prison camps in Siberia. During this trip, Harte practiced the same tactics he

had used to secure the confidence of German Ministry of War officials. Conditions in Russia and Siberia were

as bad as reported by the German press.

The Russians had a difficult time containing epidemics, especially typhus. The mail service was inadequate

and prevented POWs from communicating with their families. In addition, the imperial bureaucracy was

overwhelmed by the POW problem. The Russians could not even maintain statistics. Despite these problems,

the secretary filed favorable and sympathetic reports about the conditions he found in Siberian prison camps

with the U.S. embassy and the Russian government, stressing optimism about future Association work for

POWs.8

The Russians had a difficult time containing epidemics, especially typhus. The mail service was inadequate

and prevented POWs from communicating with their families. In addition, the imperial bureaucracy was

overwhelmed by the POW problem. The Russians could not even maintain statistics. Despite these problems,

the secretary filed favorable and sympathetic reports about the conditions he found in Siberian prison camps

with the U.S. embassy and the Russian government, stressing optimism about future Association work for

POWs.8

10 The combination of Harte's court contacts, official American support, the Russian need for assistance in providing for Central Power POWs, the concern for Russian prisoners in German camps, and Harte's constructive reports on Siberian conditions resulted in Tsarist approval of the YMCA proposals. On June 14, General Vladimir Sukhomlinov, the Russian Ministry of War, invited the two American secretaries to begin work immediately, with others to be added later. In response to Harte's success, the International Committee cabled $25,000 on July 12 to finance these operations in Russia.9

11 Harte returned to Berlin by late July 1915 to report his diplomatic successes in Petrograd and his Siberian inspection trip to German officials. The Ministry of War was delighted that the Russians had accepted the American YMCA's proposals, which would help improve conditions for German POWs in Siberia. After the meeting, Harte was convinced that German authorities would allow greater latitude for American YMCA operations in Germany. By July 27, the Ministry of War had granted Harte permission to visit all prison camps in Prussia, to establish Association huts, to distribute money and parcels sent in his care personally, to employ two German-American assistants, and to set up libraries, orchestras, and other services-"provided that similar work is done in Russia." In response, Harte cabled Petrograd that he could receive, duty-free and post-free, fifty thousand parcels for Russian POWs in Germany and supervise their distribution. The American secretary planned a meeting in Stockholm between representatives of the German and Russian Ministries of War and himself to arrange Association work between the two empires. He also decided to cram in as much work as possible in Germany over the next six weeks before taking a second trip to Russia, before the cold weather arrived. By mid-September, the importance of Harte's "shuttle diplomacy" was acknowledged by the International Committee when he was appointed International General Secretary in Europe, beginning October 1. Harte was now responsible for promoting and expanding WPA operations in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia.10

12

In Austria-Hungary, Phildius lacked the resources and contacts to undertake such diplomacy, but American

YMCA representatives were already in the field. Harte's successful trip to Russia in the late spring of

1915 impressed authorities in Vienna. Phildius met with Harte in Berlin in early July to find out what

the American had achieved in Russia for German POWs. Phildius was convinced that reciprocity between

Petrograd and Vienna was the only way to guarantee YMCA access to POWs in Austria-Hungary, and he urged

Harte to work through the U.S. Embassy in Russia. The Austro-Hungarian government wanted to negotiate

with the American YMCA in August 1915. The Ministry of War telephoned its counterparts in Berlin to invite

Harte to a conference in Vienna to discuss POW conditions in Siberia. The American Senior Secretary arrived

in the capital before his second trip to Russia to report to General Alexander von Krobatin, the Austrian

Ministry of War, on his progress in Russia. The minister acknowledged the value of the American YMCA's work

and provided one hundred thousand Marks so that Harte could begin social welfare work for Austro-Hungarian POWs in Russia.

The Minister of War also decided to allow American secretaries into the Habsburg Empire to conduct Association

POW services for Russian POWs. Harte agreed that the International Committee would finance two YMCA huts in

Braunau-in-Böhmen and Sopronnyek. Most importantly, Dual Monarchy officials permitted four American

secretaries to begin operations immediately.11

In Austria-Hungary, Phildius lacked the resources and contacts to undertake such diplomacy, but American

YMCA representatives were already in the field. Harte's successful trip to Russia in the late spring of

1915 impressed authorities in Vienna. Phildius met with Harte in Berlin in early July to find out what

the American had achieved in Russia for German POWs. Phildius was convinced that reciprocity between

Petrograd and Vienna was the only way to guarantee YMCA access to POWs in Austria-Hungary, and he urged

Harte to work through the U.S. Embassy in Russia. The Austro-Hungarian government wanted to negotiate

with the American YMCA in August 1915. The Ministry of War telephoned its counterparts in Berlin to invite

Harte to a conference in Vienna to discuss POW conditions in Siberia. The American Senior Secretary arrived

in the capital before his second trip to Russia to report to General Alexander von Krobatin, the Austrian

Ministry of War, on his progress in Russia. The minister acknowledged the value of the American YMCA's work

and provided one hundred thousand Marks so that Harte could begin social welfare work for Austro-Hungarian POWs in Russia.

The Minister of War also decided to allow American secretaries into the Habsburg Empire to conduct Association

POW services for Russian POWs. Harte agreed that the International Committee would finance two YMCA huts in

Braunau-in-Böhmen and Sopronnyek. Most importantly, Dual Monarchy officials permitted four American

secretaries to begin operations immediately.11

13

To finance the construction of the YMCA huts in Austria-Hungary, James Stokes, a long-time supporter of

Association overseas activities, donated $2,000. Stokes was deeply concerned about the spiritual welfare of

Russians given his long term interest in and support of the Miyak (Russian YMCA). On 19 December 1915,

the "James Stokes Pavilion" was officially inaugurated in Braunau-in-Böhmen with great fanfare. The

American and Spanish ambassadors, representatives of the Austrian and Danish Red Crosses, the President of the

Austrian YMCA Alliance, and members of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War attended the ceremony. The reason

for the six-month delay between official permission to open the hut and the inauguration ceremony was the lack

of skilled artisans among the POWs, who provided the bulk of the labor for the construction; the Austro-Hungarian

government had detailed a large number of prisoners out to farms for agricultural duties to bring in the harvest

of 1915.12

To finance the construction of the YMCA huts in Austria-Hungary, James Stokes, a long-time supporter of

Association overseas activities, donated $2,000. Stokes was deeply concerned about the spiritual welfare of

Russians given his long term interest in and support of the Miyak (Russian YMCA). On 19 December 1915,

the "James Stokes Pavilion" was officially inaugurated in Braunau-in-Böhmen with great fanfare. The

American and Spanish ambassadors, representatives of the Austrian and Danish Red Crosses, the President of the

Austrian YMCA Alliance, and members of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War attended the ceremony. The reason

for the six-month delay between official permission to open the hut and the inauguration ceremony was the lack

of skilled artisans among the POWs, who provided the bulk of the labor for the construction; the Austro-Hungarian

government had detailed a large number of prisoners out to farms for agricultural duties to bring in the harvest

of 1915.12

14

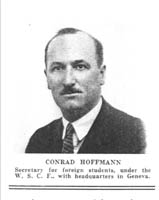

As a result of Harte and Hibbard's successful diplomacy in Europe, the International Committee dispatched

the "Flying Squadron" from New York on 3 July 1915. Eleven American YMCA secretaries volunteered to conduct

impartial war relief work for both sides for a two-month tour. The group arrived in Liverpool and awaited

assignment to either English POW camps or British soldiers. Problems soon hindered operations. The British

War Office, suspicious of pro-German sympathies among neutrals, pointed out to the English National YMCA

Council that one member of the Flying Squadron was of German origin and two others had German surnames. To

avoid potential conflicts, the International Committee assigned Conrad Hoffman to serve as the new Senior

Secretary in Germany in August 1915. This assignment would last for the duration of the war. Before

volunteering for service in Europe, Hoffman was a Student Secretary at the University of Kansas. He accepted

the position to gain additional Association experience, as well as the challenge of opening a new field. With

the support of the U.S. embassy in London, Hoffman obtained the necessary official papers and steamer tickets

to travel to Germany via the Netherlands.13

As a result of Harte and Hibbard's successful diplomacy in Europe, the International Committee dispatched

the "Flying Squadron" from New York on 3 July 1915. Eleven American YMCA secretaries volunteered to conduct

impartial war relief work for both sides for a two-month tour. The group arrived in Liverpool and awaited

assignment to either English POW camps or British soldiers. Problems soon hindered operations. The British

War Office, suspicious of pro-German sympathies among neutrals, pointed out to the English National YMCA

Council that one member of the Flying Squadron was of German origin and two others had German surnames. To

avoid potential conflicts, the International Committee assigned Conrad Hoffman to serve as the new Senior

Secretary in Germany in August 1915. This assignment would last for the duration of the war. Before

volunteering for service in Europe, Hoffman was a Student Secretary at the University of Kansas. He accepted

the position to gain additional Association experience, as well as the challenge of opening a new field. With

the support of the U.S. embassy in London, Hoffman obtained the necessary official papers and steamer tickets

to travel to Germany via the Netherlands.13

Harte Conducts a Second Trip to Russia

15

On August 21, Hoffman and Harte met to plan out a strategy for developing WPA services in Germany. By

mid-summer, the Germans had captured a large number of Russian war prisoners during the offensive into Poland.

The Germans and Austro-Hungarians had launched their attack on the Donajetz Line in late April 1915 and drove

into Galicia. They regained Przemsyl and Lemberg and crossed the Dniester River. The Central Powers occupied

all of Galicia and Bukovina by the end of June. In early July, the Teutonic allies launched a second offensive

on the Eastern Front. Dual Monarchy forces seized Lublin, Cholm, and Ivangorod in Russian Poland by August,

while the Germans drove into northern Poland and Courland, capturing Mitau, Warsaw, Brest-Litovsk, Grodno, and

Vilna by September. The need for American YMCA services in Germany had greatly increased. Hoffman took over

the WPA office in Berlin and made it a clearinghouse for information on German POWs in Russia. Hoffman requested

information about German POWs from Association secretaries in Paris, London, and Petrograd, and provided data

on Allied prisoners in Germany. The work mounted exponentially:

On August 21, Hoffman and Harte met to plan out a strategy for developing WPA services in Germany. By

mid-summer, the Germans had captured a large number of Russian war prisoners during the offensive into Poland.

The Germans and Austro-Hungarians had launched their attack on the Donajetz Line in late April 1915 and drove

into Galicia. They regained Przemsyl and Lemberg and crossed the Dniester River. The Central Powers occupied

all of Galicia and Bukovina by the end of June. In early July, the Teutonic allies launched a second offensive

on the Eastern Front. Dual Monarchy forces seized Lublin, Cholm, and Ivangorod in Russian Poland by August,

while the Germans drove into northern Poland and Courland, capturing Mitau, Warsaw, Brest-Litovsk, Grodno, and

Vilna by September. The need for American YMCA services in Germany had greatly increased. Hoffman took over

the WPA office in Berlin and made it a clearinghouse for information on German POWs in Russia. Hoffman requested

information about German POWs from Association secretaries in Paris, London, and Petrograd, and provided data

on Allied prisoners in Germany. The work mounted exponentially:

These are busier days than ever. I am on the go from 7:00 AM to 11:30 and 12:00 PM every day, going at break-neck speed and with the feverish haste to keep up with the demands made upon us. Innumerable personal interviews, hundreds of letters of inquiry that require answering, purchase of supplies and their shipment to the camps for the prisoners here in Germany, official visits and conferences-these keep us busy and help to make the days altogether too short for us. This past week has been awful from the standpoint of work and nervous strain.14

16

As the primary information contact for German POWs in Russia, Hoffman met continuously with family members

seeking information about missing soldiers or imprisoned loved ones. For many, the YMCA was their last hope.

Many family members provided money for transmission to Russia in the event a loved one was found. Harte arranged

to have his pictures of German POWs in Russia published by the local press. A wife unexpectedly identified

her husband, and a sister found her brother in the photographs. In addition to providing crucial aid to

families in wartime, Hoffman believed this work would help establish Christian Internationalism.15

As the primary information contact for German POWs in Russia, Hoffman met continuously with family members

seeking information about missing soldiers or imprisoned loved ones. For many, the YMCA was their last hope.

Many family members provided money for transmission to Russia in the event a loved one was found. Harte arranged

to have his pictures of German POWs in Russia published by the local press. A wife unexpectedly identified

her husband, and a sister found her brother in the photographs. In addition to providing crucial aid to

families in wartime, Hoffman believed this work would help establish Christian Internationalism.15

17

Hoffman contacted the International Committee in New York and determined that he would need at least five

experienced secretaries. He sought two good men to work with Russian POWs to begin operations at Worms, the

XIV Army Corps (Carlsruhe), and the XVIII Army Corps (Frankfurt-am-Main) in western Germany as well as at

Altdamm, Stargard, Czersk, Danzig, Tuchel, and Bütow, in eastern Germany, plus Parchim, Güstrow, and

Frankfurt-an-der-Oder in central Germany.

Hoffman contacted the International Committee in New York and determined that he would need at least five

experienced secretaries. He sought two good men to work with Russian POWs to begin operations at Worms, the

XIV Army Corps (Carlsruhe), and the XVIII Army Corps (Frankfurt-am-Main) in western Germany as well as at

Altdamm, Stargard, Czersk, Danzig, Tuchel, and Bütow, in eastern Germany, plus Parchim, Güstrow, and

Frankfurt-an-der-Oder in central Germany.

These camps each held between ten thousand and sixty thousand POWs. Association secretaries would be able to reach a

large number of men. Hoffman also wanted an experienced Red Triangle worker to begin relief operations with

French prisoners. While Indian POWs were certainly in need of YMCA assistance, they were too few in number

to justify a secretary working solely for their welfare.

These camps each held between ten thousand and sixty thousand POWs. Association secretaries would be able to reach a

large number of men. Hoffman also wanted an experienced Red Triangle worker to begin relief operations with

French prisoners. While Indian POWs were certainly in need of YMCA assistance, they were too few in number

to justify a secretary working solely for their welfare.

One area that did need immediate attention was relief operations for working parties. During the summer of

1915, the Germans began to increase the number of POWs they sent out of main prison camps on work details,

and Hoffman needed a secretary to look after the needs of these men. He also requested an office manager to

supervise operations at the WPA Office. He had one proviso; he did not want any preachers unless they had

Association training.16

One area that did need immediate attention was relief operations for working parties. During the summer of

1915, the Germans began to increase the number of POWs they sent out of main prison camps on work details,

and Hoffman needed a secretary to look after the needs of these men. He also requested an office manager to

supervise operations at the WPA Office. He had one proviso; he did not want any preachers unless they had

Association training.16

18

In preparation for the International General Secretary's second trip to Russia, Harte and Hoffman toured

German prison camps during August 1915. They visited the officers' camp at Crefeld, the Allied officers'

camp at the old fort in Mainz-Castell (primarily British officers, but holding some French and Russian officers

as well), and the military hospital in Wiesbaden. They also revisited the prison camp at Crossen-an-der-Oder.

Harte described an idyllic prison camp that featured a well-equipped hospital, kitchen, bakery, bank, post office,

shoemaker's shop, arts and crafts shops, athletic field, and gardens.

In preparation for the International General Secretary's second trip to Russia, Harte and Hoffman toured

German prison camps during August 1915. They visited the officers' camp at Crefeld, the Allied officers'

camp at the old fort in Mainz-Castell (primarily British officers, but holding some French and Russian officers

as well), and the military hospital in Wiesbaden. They also revisited the prison camp at Crossen-an-der-Oder.

Harte described an idyllic prison camp that featured a well-equipped hospital, kitchen, bakery, bank, post office,

shoemaker's shop, arts and crafts shops, athletic field, and gardens.

Though not luxurious, the facility was very attractive and had the air of a summer resort. The camp also

featured neat and well-kept streets, green grass, flower beds, and an Association hall. This hut was built

through the efforts of the camp commandant, Pastor Schrenk, and POW labor. It had one large room for church

services, lectures, and concerts, a reading and writing room, and small rooms for a library, musical practice,

and study. There were 1,200 books in the library for the Russian, British, and French POWs in the prison. The

sanitation facilities at Crossen-an-der-Oder were outstanding, with few cases of illness and even fewer deaths,

and relations between the Russian Orthodox priest and the Association were excellent. This optimistic report

reflected Harte's emphasis on the positive aspects of prison camp life. Later in this trip, the American

secretaries met with German YMCA workers in Barmen, in Westphalia. During the Barmen Conference, the

Association workers fully discussed the American plans. German YMCA officials promised their hearty

cooperation and commitment to the WPA program. The American secretaries then returned to Berlin, where Harte

prepared for his trip to Russia.17

Though not luxurious, the facility was very attractive and had the air of a summer resort. The camp also

featured neat and well-kept streets, green grass, flower beds, and an Association hall. This hut was built

through the efforts of the camp commandant, Pastor Schrenk, and POW labor. It had one large room for church

services, lectures, and concerts, a reading and writing room, and small rooms for a library, musical practice,

and study. There were 1,200 books in the library for the Russian, British, and French POWs in the prison. The

sanitation facilities at Crossen-an-der-Oder were outstanding, with few cases of illness and even fewer deaths,

and relations between the Russian Orthodox priest and the Association were excellent. This optimistic report

reflected Harte's emphasis on the positive aspects of prison camp life. Later in this trip, the American

secretaries met with German YMCA workers in Barmen, in Westphalia. During the Barmen Conference, the

Association workers fully discussed the American plans. German YMCA officials promised their hearty

cooperation and commitment to the WPA program. The American secretaries then returned to Berlin, where Harte

prepared for his trip to Russia.17

19

The International General Secretary left Berlin on 1 October 1915 on his second trip to Russia. Harte spent

six weeks touring prison camps in Turkestan and Siberia to assess Russian preparations for the approaching

winter. The German government provided him with two hundred thousand Marks to distribute to needy German POWs. Harte also

received fourteen thousand Marks from family members, in sums ranging from five to five hundred Marks, for delivery to

individual prisoners. He carried three sacks of Liebesgaben (care packages from loved ones in Germany),

one sack of letters and cards, two cases of musical instruments, a basket trunk with additional parcels, and one

box of songbooks of German folk songs in addition to his own baggage. Harte was accompanied by a Russian captain

who had lost his leg and been captured. This officer was the nephew of the Russian minister to Stockholm, and

Harte sought to arrange the release of German invalid prisoners in exchange for him. In addition, the Germans

wanted to demonstrate Harte's influence with their Ministry of War. This gesture, another example of the Principle

of Reciprocity, would help improve relations between the two belligerent nations and represented an important step

towards the exchange of seriously sick and invalid prisoners. Harte stopped in Vienna to discuss WPA operations

with the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War, and described the American POW relief program in detail. Eager to provide

assistance to Dual Monarchy prisoners in Russia, the Austro-Hungarian government readily endorsed Harte's program

and agreed to allow American secretaries to begin operations on Austro-Hungarian territory. Austro-Hungarian

authorities also provided the American secretary with one hundred thousand Marks to disseminate to Dual Monarchy prisoners to

improve their condition. In addition, Harte carried 120,000 Marks from American contributors for Central Power

POWs.18

The International General Secretary left Berlin on 1 October 1915 on his second trip to Russia. Harte spent

six weeks touring prison camps in Turkestan and Siberia to assess Russian preparations for the approaching

winter. The German government provided him with two hundred thousand Marks to distribute to needy German POWs. Harte also

received fourteen thousand Marks from family members, in sums ranging from five to five hundred Marks, for delivery to

individual prisoners. He carried three sacks of Liebesgaben (care packages from loved ones in Germany),

one sack of letters and cards, two cases of musical instruments, a basket trunk with additional parcels, and one

box of songbooks of German folk songs in addition to his own baggage. Harte was accompanied by a Russian captain

who had lost his leg and been captured. This officer was the nephew of the Russian minister to Stockholm, and

Harte sought to arrange the release of German invalid prisoners in exchange for him. In addition, the Germans

wanted to demonstrate Harte's influence with their Ministry of War. This gesture, another example of the Principle

of Reciprocity, would help improve relations between the two belligerent nations and represented an important step

towards the exchange of seriously sick and invalid prisoners. Harte stopped in Vienna to discuss WPA operations

with the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War, and described the American POW relief program in detail. Eager to provide

assistance to Dual Monarchy prisoners in Russia, the Austro-Hungarian government readily endorsed Harte's program

and agreed to allow American secretaries to begin operations on Austro-Hungarian territory. Austro-Hungarian

authorities also provided the American secretary with one hundred thousand Marks to disseminate to Dual Monarchy prisoners to

improve their condition. In addition, Harte carried 120,000 Marks from American contributors for Central Power

POWs.18

20

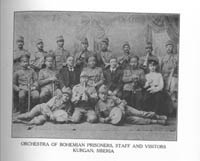

Successfully concluding his negotiations in Vienna, Harte traveled north to Stockholm. He met with the representatives of the Red Cross: Ira Morris (the U.S. Minister to Sweden), the Russian Minister to Sweden, and Swedish relief agencies interested in providing assistance to POWs in Russia. He showed motion pictures of relief operations in German prison camps at the royal palace. Most importantly, he demonstrated the practical effects of American charity for unfortunate POWs. Harte then continued to Petrograd, arriving in November 1915. He met with a group of influential Russian officers and reviewed the benefits of POW relief services for Russian war prisoners in Central Power prison camps. He emphasized the importance of establishing similar welfare operations for German, Austrian, and Hungarian POWs in prison camps across the Russian Empire. Harte and these officials set up the Russian Committee on War Prisoners' Aid on November 30, which created a legal entity in Russia able to dispense assistance to prisoners. This committee became the primary Russian organization for coordinating POW services between Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary, and established the foundation for YMCA prisoner relief operations in Eastern Europe. Having officially established WPA operations in Russia, Harte then embarked on a six-week tour of Russian prison camps in Turkestan and Siberia. The American YMCA secretary boarded a train on the Trans-Siberian Railway and Harte arrived in Irkutsk on 23 December 1915, the first prison camp on his itinerary. He visited six more prison facilities in the Russian Far East before he arrived in the vicinity of Vladivostok on 12 January 1916. Harte then proceeded west on the Chinese Eastern Railway across northern Manchuria and resumed his inspection of Russian prison camps at Dauriya on January 18. He stopped at eleven more prison facilities in central Siberia on his trip back to European Russia. His last prison camp inspection took place at Kurgan on February 9, before he proceeded to Petrograd to report his findings. During this tour, Harte distributed money, set up libraries, and identified camps that could benefit from Association halls. Harte's success in Russia firmly established WPA operations in the Tsarist Empire and laid the ground work for the expansion of POW relief service in Central and Western Europe.19

Successfully concluding his negotiations in Vienna, Harte traveled north to Stockholm. He met with the representatives of the Red Cross: Ira Morris (the U.S. Minister to Sweden), the Russian Minister to Sweden, and Swedish relief agencies interested in providing assistance to POWs in Russia. He showed motion pictures of relief operations in German prison camps at the royal palace. Most importantly, he demonstrated the practical effects of American charity for unfortunate POWs. Harte then continued to Petrograd, arriving in November 1915. He met with a group of influential Russian officers and reviewed the benefits of POW relief services for Russian war prisoners in Central Power prison camps. He emphasized the importance of establishing similar welfare operations for German, Austrian, and Hungarian POWs in prison camps across the Russian Empire. Harte and these officials set up the Russian Committee on War Prisoners' Aid on November 30, which created a legal entity in Russia able to dispense assistance to prisoners. This committee became the primary Russian organization for coordinating POW services between Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary, and established the foundation for YMCA prisoner relief operations in Eastern Europe. Having officially established WPA operations in Russia, Harte then embarked on a six-week tour of Russian prison camps in Turkestan and Siberia. The American YMCA secretary boarded a train on the Trans-Siberian Railway and Harte arrived in Irkutsk on 23 December 1915, the first prison camp on his itinerary. He visited six more prison facilities in the Russian Far East before he arrived in the vicinity of Vladivostok on 12 January 1916. Harte then proceeded west on the Chinese Eastern Railway across northern Manchuria and resumed his inspection of Russian prison camps at Dauriya on January 18. He stopped at eleven more prison facilities in central Siberia on his trip back to European Russia. His last prison camp inspection took place at Kurgan on February 9, before he proceeded to Petrograd to report his findings. During this tour, Harte distributed money, set up libraries, and identified camps that could benefit from Association halls. Harte's success in Russia firmly established WPA operations in the Tsarist Empire and laid the ground work for the expansion of POW relief service in Central and Western Europe.19

The American YMCA Offers POW Work in Italy

21

After Italy's entry into the war, the American YMCA sent representatives to Rome to offer POW services as part

of the Principle of Reciprocity.The president of the National Council of the Italian YMCA wrote to the World Committee of the World's Alliance

of YMCAs in Geneva for assistance in May 1915. Carlisle Hibbard and Darius Alton Davis (who would replace Hibbard

as the American YMCA's Senior Secretary by the summer of 1915, when the latter returned to New York to supervise

American YMCA relief in Europe as a key member of the International Committee) arrived from Paris in June

1915.20

After Italy's entry into the war, the American YMCA sent representatives to Rome to offer POW services as part

of the Principle of Reciprocity.The president of the National Council of the Italian YMCA wrote to the World Committee of the World's Alliance

of YMCAs in Geneva for assistance in May 1915. Carlisle Hibbard and Darius Alton Davis (who would replace Hibbard

as the American YMCA's Senior Secretary by the summer of 1915, when the latter returned to New York to supervise

American YMCA relief in Europe as a key member of the International Committee) arrived from Paris in June

1915.20

22

At this point, Italy had been at war with Austria-Hungary for only a few weeks, and the Italians had not captured

a significant number of prisoners.

At this point, Italy had been at war with Austria-Hungary for only a few weeks, and the Italians had not captured

a significant number of prisoners.

The Italian Army was conducting a series of offensives along the Isonzo, a sixty-mile front. The Italian commander, General Luigi Cardorna, sought to seize the Austro-Hungarian mountain

strongholds before seasoned Austrian divisions could arrive from the Galician Front. The Habsburg commander,

Archduke Eugene, held the strategic bridgeheads of Gorizia and Tolmino, and never allowed the Italians to advance

more than a few miles.21

The Italian Army was conducting a series of offensives along the Isonzo, a sixty-mile front. The Italian commander, General Luigi Cardorna, sought to seize the Austro-Hungarian mountain

strongholds before seasoned Austrian divisions could arrive from the Galician Front. The Habsburg commander,

Archduke Eugene, held the strategic bridgeheads of Gorizia and Tolmino, and never allowed the Italians to advance

more than a few miles.21

23

Hibbard and Davis met with Italian government leaders to offer Association welfare services for POWs and Italian

soldiers, but failed to reach any substantive results. Instead, they met with leaders of the Student Movement

and City Associations of Rome and Genoa to help them assist Italian troops and POWs. The International Committee

forwarded $1,000 to the Italian branch of the World's Student Christian Federation for relief work for soldiers

and POWs in Italy, and the English National YMCA Council offered similar support. Despite this foreign aid, the

Italian government was focused on military mobilization, and was not concerned with prisoner welfare at this point

in the war.22

Hibbard and Davis met with Italian government leaders to offer Association welfare services for POWs and Italian

soldiers, but failed to reach any substantive results. Instead, they met with leaders of the Student Movement

and City Associations of Rome and Genoa to help them assist Italian troops and POWs. The International Committee

forwarded $1,000 to the Italian branch of the World's Student Christian Federation for relief work for soldiers

and POWs in Italy, and the English National YMCA Council offered similar support. Despite this foreign aid, the

Italian government was focused on military mobilization, and was not concerned with prisoner welfare at this point

in the war.22

24

Davis returned in October 1915 to renew his contacts with Italian officials. By this time, the American YMCA

had begun POW operations for Central Power prisoners in France, and Davis brought letters of support from

French officials. The U.S. Ambassador to Italy, Thomas Nelson Page, also provided Davis with an introduction,

which enabled the secretary to meet with General Paolo Springardi, the President of the War Prisoners' Commission;

Signor Vigliani, the Assistant Minister of the Interior; the Assistant Minister of War; the Assistant Minister of

Foreign Affairs; and the Assistant Minister of Finance. Davis' mission was also bolstered by the American YMCA's

successful POW relief programs for Allied prisoners in the Dual Monarchy, a service that would benefit Italian

POWs held by the Austro-Hungarians. By this time, the Italians had completed their third offensive against the

Isonzo Front, and had captured a number of Austro-Hungarian POWs. With the support of French and American

officials, Davis enjoyed a favorable reception from Italian authorities. On 22 November 1915, Vigliani and

Springardi extended official authorization for Davis to visit civilian internment camps on Sardinia. This

authorization included permission to distribute books and assistance to the interned Austro-Hungarian

civilians.23

Davis returned in October 1915 to renew his contacts with Italian officials. By this time, the American YMCA

had begun POW operations for Central Power prisoners in France, and Davis brought letters of support from

French officials. The U.S. Ambassador to Italy, Thomas Nelson Page, also provided Davis with an introduction,

which enabled the secretary to meet with General Paolo Springardi, the President of the War Prisoners' Commission;

Signor Vigliani, the Assistant Minister of the Interior; the Assistant Minister of War; the Assistant Minister of

Foreign Affairs; and the Assistant Minister of Finance. Davis' mission was also bolstered by the American YMCA's

successful POW relief programs for Allied prisoners in the Dual Monarchy, a service that would benefit Italian

POWs held by the Austro-Hungarians. By this time, the Italians had completed their third offensive against the

Isonzo Front, and had captured a number of Austro-Hungarian POWs. With the support of French and American

officials, Davis enjoyed a favorable reception from Italian authorities. On 22 November 1915, Vigliani and

Springardi extended official authorization for Davis to visit civilian internment camps on Sardinia. This

authorization included permission to distribute books and assistance to the interned Austro-Hungarian

civilians.23

25

During a twelve-day trip, Davis visited seventeen centers on the island and inspected approximately one-fourth

of the interned population. Davis did not find concentration camps on Sardinia; instead, the Italians had

distributed the interned Austro-Hungarians to villages across the island. They were free to rent their own

rooms and move freely around the towns to which they were assigned. If interned civilians lacked their own

means of support, the Italian government provided a subsidy so that the civilians could arrange their own

food and shelter. In relation to other countries, poverty among the Austro-Hungarian internees was comparatively

minimal. During this visit, Davis provided encouragement and good cheer to these internees. The American

secretary was the first foreign agent permitted to meet the captives since the beginning of the war. Davis

made it easier for Austro-Hungarian internees to receive books and reading matter, and he worked to improve

the correspondence system so that internees could contact friends and family at home.24

During a twelve-day trip, Davis visited seventeen centers on the island and inspected approximately one-fourth

of the interned population. Davis did not find concentration camps on Sardinia; instead, the Italians had

distributed the interned Austro-Hungarians to villages across the island. They were free to rent their own

rooms and move freely around the towns to which they were assigned. If interned civilians lacked their own

means of support, the Italian government provided a subsidy so that the civilians could arrange their own

food and shelter. In relation to other countries, poverty among the Austro-Hungarian internees was comparatively

minimal. During this visit, Davis provided encouragement and good cheer to these internees. The American

secretary was the first foreign agent permitted to meet the captives since the beginning of the war. Davis

made it easier for Austro-Hungarian internees to receive books and reading matter, and he worked to improve

the correspondence system so that internees could contact friends and family at home.24

26 Davis wrote a favorable report about the conditions on Sardinia and forwarded a copy to General Springardi. When Davis returned to Rome in early December, he found Springardi willing to let him visit any military prison he chose. Davis studied the situation and wrote a report for the War Prisoners' Commission outlining what the American YMCA could offer in terms of work with POWs. Davis decided to visit five forts/prisons containing POWs in the Genoa military region, before returning to Geneva to resume his duties as Senior Secretary for Europe.25

27 From the beginning, Davis made it clear to Italian officials that his duty was not to conduct prison inspections. Instead, the YMCA sought to cooperate with the Italian government to promote the moral and intellectual health of POWs in Italian camps. This was an important consideration, especially since a strong national distaste for alien influences on military policy existed in Italy. That the American YMCA was a Protestant social welfare organization attempting to increase its influence in Catholic Italy did not ease the preliminary negotiations. During his visits to the Genoa prison camps, Davis noted that the Austro-Hungarian prisoners were well supplied with food, clothing, and lodging, but lacked useful occupations and recreation to maintain their sanity and moral health. While the Italian government did not ban the distribution of reading material to POWs, no organization existed to provide such a service. Dr. Jean-Henri-Adolphe d'Espine, Vice President of the International Red Cross Society, inspected Italian military prison camps shortly after Davis' trip and came to similar conclusions. D'Espine found that the POWs needed to occupy their time, and noted that nothing was as demoralizing as "constant idleness." He was encouraged to learn that the YMCA was prepared to send books, games, and music to war prisoners, items that the International Red Cross did not distribute. Davis arranged with Red Cross authorities to supply requests through the Geneva organization. In return, d'Espine promised to write to military authorities in Rome to support the American YMCA WPA program. Davis also found that the Italian government had already started a school for illiterates and offered Italian classes to POWs. Camp officials were overwhelmed by the number of languages spoken by prisoners from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, since comparatively few spoke German. The prisoners requested books from Davis, especially scientific works, and musical instruments to help them pass time. This initial work represented the Association's first steps towards establishing POW work in Italy.26

28 Inspired by Davis' success with Austro-Hungarian POWs, the International Committee authorized funds for War Prisoners' Aid work in Italy; on 11 December 1915, John R. Mott allocated $5,000 to establish WPA work in Italian POW camps. The General Secretary declared: "A complete history of this work in behalf of millions of prisoners in all the warring lands would constitute a new record in humanitarian endeavor."27 Due to delays in the mail, however, the World's Committee in Geneva did not receive this authorization until December 31. As a result, POWs incarcerated in Italy did not receive the customary Christmas cheer from the YMCA that prisoners in other countries enjoyed. American YMCA secretaries recognized that the Christmas season was particularly difficult for war prisoners, far from home and loved ones, and with no end to the war in sight.28

29

In January 1916, Dr. Walter Lowrie, an American clergyman living in Rome, replaced Davis as the American

Association's representative in Italy. In an important breakthrough, the Italian government requested that

Ambassador Penfield inspect the Austro-Hungarian prison camp in Mauthausen, in Upper Austria. The government

was concerned about the treatment of Italian POWs. With the approval of Ambassador Page, Davis inspected the

camp in June 1916 to assess conditions. As a gesture of good faith, the Dual Monarchy opened Mauthausen to the

YMCA and permitted the Association to construct a hut. In exchange, the Italian government agreed in July 1916

to grant the American YMCA access to the prison camp in Ancona, and allowed the establishment of an Association

hut. The Italians granted further concessions to Lowrie's replacement, M. B. Rideout, in November 1916. The

Association gained access and permission to build huts at Avezzano and Padua in early December, the two largest

prison camps in Italy.29

In January 1916, Dr. Walter Lowrie, an American clergyman living in Rome, replaced Davis as the American

Association's representative in Italy. In an important breakthrough, the Italian government requested that

Ambassador Penfield inspect the Austro-Hungarian prison camp in Mauthausen, in Upper Austria. The government

was concerned about the treatment of Italian POWs. With the approval of Ambassador Page, Davis inspected the

camp in June 1916 to assess conditions. As a gesture of good faith, the Dual Monarchy opened Mauthausen to the

YMCA and permitted the Association to construct a hut. In exchange, the Italian government agreed in July 1916

to grant the American YMCA access to the prison camp in Ancona, and allowed the establishment of an Association

hut. The Italians granted further concessions to Lowrie's replacement, M. B. Rideout, in November 1916. The

Association gained access and permission to build huts at Avezzano and Padua in early December, the two largest

prison camps in Italy.29

30

Despite these promising advancements, Italian delays in initiating these POW relief projects almost led to

Austria-Hungary to retaliate by limiting American YMCA operations. Italian procrastination in the construction

of YMCA facilities, due to insufficient funding and incorrect permits, forced the Austro-Hungarian government

to threaten to close down YMCA operations for Italian POWs. Davis immediately responded to the crisis by

contacting Mott, and the International Committee cabled $5,000 to finance Association construction projects in

Italy. The Italians reissued permits, and disaster was narrowly avoided. Despite the prompt American response,

Italian construction proceeded slowly due to the scarcity of building materials, labor, and transportation, but

the Austro-Hungarian government permitted the YMCA to continue to develop its program for Italian prisoners.30

Despite these promising advancements, Italian delays in initiating these POW relief projects almost led to

Austria-Hungary to retaliate by limiting American YMCA operations. Italian procrastination in the construction

of YMCA facilities, due to insufficient funding and incorrect permits, forced the Austro-Hungarian government

to threaten to close down YMCA operations for Italian POWs. Davis immediately responded to the crisis by

contacting Mott, and the International Committee cabled $5,000 to finance Association construction projects in

Italy. The Italians reissued permits, and disaster was narrowly avoided. Despite the prompt American response,

Italian construction proceeded slowly due to the scarcity of building materials, labor, and transportation, but

the Austro-Hungarian government permitted the YMCA to continue to develop its program for Italian prisoners.30

Serbia and POW Diplomacy

31

The proverbial "fly in the ointment" of reciprocal diplomacy was Serbia. The World's Committee of the World's

Alliance negotiated with the Serbian government for services for Dual Monarchy POWs in that kingdom. Dr.

Paul Des Gouttes, a member of the World's Committee and the Honorary General Secretary of the International

Red Cross Committee, contacted the Serbian Red Cross Society in June 1915 and conveyed the Austro-Hungarian

government's demand for POW service reciprocity. Des Gouttes proposed the construction of a YMCA hut in

Serbia, which would clear the way for a third hut in Austria-Hungary for Serbian prisoners. Mott agreed to

finance this project in September, and the Serbian government granted the Association permission to begin

POW services. This permission came too late, however, as a joint German, Austro-Hungarian, and Bulgarian

offensive overran Serbia in October 1915. Of the sixty thousand Central Power POWs held by the Serbs, two-thirds

perished in the retreat. The survivors were interned on the island of Sardinia and eventually transferred

to labor detachments in France. The Austro-Hungarian demand for POW service reciprocity became a moot point

after Serbia was occupied.31

The proverbial "fly in the ointment" of reciprocal diplomacy was Serbia. The World's Committee of the World's

Alliance negotiated with the Serbian government for services for Dual Monarchy POWs in that kingdom. Dr.

Paul Des Gouttes, a member of the World's Committee and the Honorary General Secretary of the International

Red Cross Committee, contacted the Serbian Red Cross Society in June 1915 and conveyed the Austro-Hungarian

government's demand for POW service reciprocity. Des Gouttes proposed the construction of a YMCA hut in

Serbia, which would clear the way for a third hut in Austria-Hungary for Serbian prisoners. Mott agreed to

finance this project in September, and the Serbian government granted the Association permission to begin

POW services. This permission came too late, however, as a joint German, Austro-Hungarian, and Bulgarian

offensive overran Serbia in October 1915. Of the sixty thousand Central Power POWs held by the Serbs, two-thirds

perished in the retreat. The survivors were interned on the island of Sardinia and eventually transferred

to labor detachments in France. The Austro-Hungarian demand for POW service reciprocity became a moot point

after Serbia was occupied.31

Bulgaria and War Prisoner Relief

32

Bulgaria entered the war on 12 October 1915 on the side of the Central Powers to participate in the

dismemberment of Serbia. The Serbs had repulsed two Austro-Hungarian invasion attempts since the beginning

of the war in July 1914. Stymied by Serbian obstinacy, the Central Powers courted Tsar Ferdinand in 1915

and easily persuaded the Bulgarians to join ranks against Serbia. The Balkans was an unstable region long

before the general European war began. Bulgaria had allied with Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece in the First

Balkan League, and went to war against Turkey in 1912. Ottoman misrule in Macedonia sparked the First Balkan

War, and within six weeks the Balkan allies drove within twenty-five miles of Constantinople. The Turks

sued for peace and signed the Treaty of London in January 1913. The Ottomans surrendered most of their

European territory, and the Bulgarians emerged the clear victors, but peace in the Balkans was far from

secure.32

Bulgaria entered the war on 12 October 1915 on the side of the Central Powers to participate in the

dismemberment of Serbia. The Serbs had repulsed two Austro-Hungarian invasion attempts since the beginning

of the war in July 1914. Stymied by Serbian obstinacy, the Central Powers courted Tsar Ferdinand in 1915

and easily persuaded the Bulgarians to join ranks against Serbia. The Balkans was an unstable region long

before the general European war began. Bulgaria had allied with Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece in the First

Balkan League, and went to war against Turkey in 1912. Ottoman misrule in Macedonia sparked the First Balkan

War, and within six weeks the Balkan allies drove within twenty-five miles of Constantinople. The Turks

sued for peace and signed the Treaty of London in January 1913. The Ottomans surrendered most of their

European territory, and the Bulgarians emerged the clear victors, but peace in the Balkans was far from

secure.32

33 Unsatisfied with the peace terms, Serbia, Romania, Greece, and Turkey joined forces, seeking to redress the balance of power in the region. Not satiated with their gains, the Bulgarians launched a preemptive strike against Serbia and Greece to gain control of Macedonia in June 1913. The Bulgarian invasion stalled, and Romania and Turkey struck against Bulgaria. Caught off guard, the Bulgarians had no other choice but to submit to an armistice, and in August 1913, the Bulgarians signed the Treaty of Bucharest. The Bulgarians lost most of the territory they had won in the First Balkan War, retaining only a small strip of land along the Aegean coast. When German and Austro-Hungarian officials approached in 1915, the Bulgarians were eager to humble the Serbians.33

34

In October 1915, the Bulgarians mobilized their 360,000-man army, just as a 250,000-man Austro-German

army struck northern Serbia. The Serbs tenaciously resisted the Austro-German invasion, but their position

became critical when two Bulgarian armies flooded into eastern Serbia. Caught between the Bulgarian and the

Austro-German armies, the Serbians had no choice but to retreat. Their defenses collapsed by December, and