Table of Contents

Chapter 9

The American YMCA and WPA Operations in Austria-Hungary

1

Christian Phildius remained in charge of YMCA POW operations in Austria-Hungary until the summer of 1916, when Edgar

F. MacNaughten arrived. The International Committee appointed MacNaughten to the post of Senior Secretary, and in

that capacity he supervised YMCA workers in the Dual Monarchy. He had served on the Army and Navy Department of the

International Committee and had extensive Association experience.

Christian Phildius remained in charge of YMCA POW operations in Austria-Hungary until the summer of 1916, when Edgar

F. MacNaughten arrived. The International Committee appointed MacNaughten to the post of Senior Secretary, and in

that capacity he supervised YMCA workers in the Dual Monarchy. He had served on the Army and Navy Department of the

International Committee and had extensive Association experience.

Part of the American YMCA's strategy to streamline welfare work for prisoners was to establish War Prisoners'

Aid organizations in belligerent capitals. Association secretaries worked with committees of national welfare

organizations and leading citizens to coordinate welfare programs and make POW work as efficient as possible.

The first major WPA organization was set up in Russia in November 1915, and was soon followed by similar

organizations in Germany and the Dual Monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian WPA was the most successful of these

organizations in gaining official sanction by the imperial government. Under the patronage of Franz Salvator,

Archduke of Austria-Tuscany, who served as honorary president, the WPA in the Habsburg Empire grew in importance.

Part of the American YMCA's strategy to streamline welfare work for prisoners was to establish War Prisoners'

Aid organizations in belligerent capitals. Association secretaries worked with committees of national welfare

organizations and leading citizens to coordinate welfare programs and make POW work as efficient as possible.

The first major WPA organization was set up in Russia in November 1915, and was soon followed by similar

organizations in Germany and the Dual Monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian WPA was the most successful of these

organizations in gaining official sanction by the imperial government. Under the patronage of Franz Salvator,

Archduke of Austria-Tuscany, who served as honorary president, the WPA in the Habsburg Empire grew in importance.

2

This agency became an integral part of the general welfare services of the Austrian and Hungarian Red Cross

Societies in the spring of 1916. Baron Markus von Spiegelfeld, President of the WPA Committee of the Austrian Red Cross,

quickly embraced the goals of the American YMCA. He used his influence to expand the YMCA's POW activities in

Russia and to the Ottoman Empire. MacNaughten was appointed a member of both Red Cross committees, which gave the

American YMCA official status in the Dual Monarchy. As a result, the secretaries' privileges in the empire were

very liberal, and government officials rarely interfered with their activities. For example, American YMCA secretaries

received permission to reside inside Austro-Hungarian prison camps and were allowed unrestricted right of entry,

whereas Association secretaries in other countries were normally limited to only a few hours of visitation per

day.1

This agency became an integral part of the general welfare services of the Austrian and Hungarian Red Cross

Societies in the spring of 1916. Baron Markus von Spiegelfeld, President of the WPA Committee of the Austrian Red Cross,

quickly embraced the goals of the American YMCA. He used his influence to expand the YMCA's POW activities in

Russia and to the Ottoman Empire. MacNaughten was appointed a member of both Red Cross committees, which gave the

American YMCA official status in the Dual Monarchy. As a result, the secretaries' privileges in the empire were

very liberal, and government officials rarely interfered with their activities. For example, American YMCA secretaries

received permission to reside inside Austro-Hungarian prison camps and were allowed unrestricted right of entry,

whereas Association secretaries in other countries were normally limited to only a few hours of visitation per

day.1

3

The American YMCA set up Association POW programs in thirty-four prison camps in Austria-Hungary between December

1915 and October 1917 (out of a total of fifty war prisons in the Dual Monarchy). The American Association established

POW programs in all of the empire's twenty-eight major prison camps, which included a YMCA hut or barrack and assigned

personnel. Fifteen secretaries (all but one Americans) conducted the operations in these prison camps during this time.

The International Committee assigned Dr. Julius F. Hecker to assist MacNaughten and supervise the work for Russian

POWs. He was born in Petrograd of German-French heritage, and received his education in Russian schools. He kept

his German citizenship until he traveled to the United States when he was twenty-one and applied for naturalization.

After receiving his doctorate from Columbia University, Hecker directed the Methodist Church Mission for Russians

in New York City. His command of Russian, English, and German permitted him to work equally well with Austro-Hungarian

officials, POWs, and his fellow American secretaries. The Kriegsgefangenenhilfe (War Prisoners' Aid) headquarters were established

in Vienna in March 1916 with Jean Schoop, a Swiss secretary, as the initial staff member. Schoop was a German Swiss

national with considerable Association experience. From 1902 to 1914, Schoop had been the General Secretary of the

German YMCA in Petrograd, and he spoke fluent German, English, and Russian, making him ideal for work in Austria-Hungary.

The Vienna office served as the Central Bureau for YMCA POW operations in the Dual Monarchy. Louis P. Penningroth arrived

from the United States in March 1916; after initially conducting field work at Braunau-in-Böhmen, MacNaughten

reassigned Penningroth to Vienna to coordinate WPA operations from July 1916 to March 1917, when he was scheduled to

be transfer to Sofia to become the Senior Secretary for American YMCA POW operations in Bulgaria. Penningroth was

assisted in Vienna by Lars Stubbe Teglbjärg, a Danish secretary assigned to the American YMCA POW service, from

November 1916 to September 1918. MacNaughten served the as Senior Secretary and oversaw all YMCA operations until his

departure shortly before the U.S. declared war on Austria-Hungary.2

The American YMCA set up Association POW programs in thirty-four prison camps in Austria-Hungary between December

1915 and October 1917 (out of a total of fifty war prisons in the Dual Monarchy). The American Association established

POW programs in all of the empire's twenty-eight major prison camps, which included a YMCA hut or barrack and assigned

personnel. Fifteen secretaries (all but one Americans) conducted the operations in these prison camps during this time.

The International Committee assigned Dr. Julius F. Hecker to assist MacNaughten and supervise the work for Russian

POWs. He was born in Petrograd of German-French heritage, and received his education in Russian schools. He kept

his German citizenship until he traveled to the United States when he was twenty-one and applied for naturalization.

After receiving his doctorate from Columbia University, Hecker directed the Methodist Church Mission for Russians

in New York City. His command of Russian, English, and German permitted him to work equally well with Austro-Hungarian

officials, POWs, and his fellow American secretaries. The Kriegsgefangenenhilfe (War Prisoners' Aid) headquarters were established

in Vienna in March 1916 with Jean Schoop, a Swiss secretary, as the initial staff member. Schoop was a German Swiss

national with considerable Association experience. From 1902 to 1914, Schoop had been the General Secretary of the

German YMCA in Petrograd, and he spoke fluent German, English, and Russian, making him ideal for work in Austria-Hungary.

The Vienna office served as the Central Bureau for YMCA POW operations in the Dual Monarchy. Louis P. Penningroth arrived

from the United States in March 1916; after initially conducting field work at Braunau-in-Böhmen, MacNaughten

reassigned Penningroth to Vienna to coordinate WPA operations from July 1916 to March 1917, when he was scheduled to

be transfer to Sofia to become the Senior Secretary for American YMCA POW operations in Bulgaria. Penningroth was

assisted in Vienna by Lars Stubbe Teglbjärg, a Danish secretary assigned to the American YMCA POW service, from

November 1916 to September 1918. MacNaughten served the as Senior Secretary and oversaw all YMCA operations until his

departure shortly before the U.S. declared war on Austria-Hungary.2

4

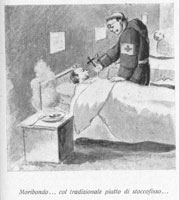

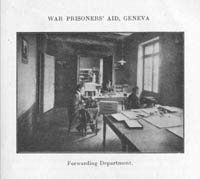

The Central Bureau in Vienna worked to maintain daily operations in the prison camps by providing supplies,

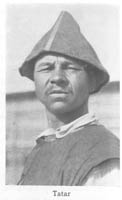

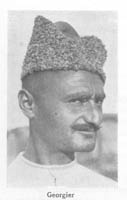

communications, and personnel as efficiently as possible. Most of the Russian, Serbian, Romanian, and Italian

prisoners were poor and lacked education. Their families did not have the resources to send packages to improve

their condition, nor could their governments extend much help. As the war dragged on and the Allied blockade of

the Central Powers became more effective, living standards for Austro-Hungarian prisoners fell drastically. By

1917, prison rations were limited to cabbage or beef soup, one-quarter loaf of black bread per day, and an

occasional small portion of meat for each prisoner. In addition, many POWs were insufficiently clad, especially

if they were captured during summer campaigning, and coal became unobtainable. The American YMCA was not set up

to conduct physical relief operations, but conditions became so bad that secretaries made every effort to assist

welfare agencies and supplement relief supplies. Because of the extensive network the American YMCA had established

in the Austro-Hungarian war prison system, the WPA became the distributing agent and cooperated with the majority

of welfare organizations such as the Russian Red Cross, the Russian Relief Fund, and Swedish relief organizations.

Austro-Hungarian regulations on purchasing food were very strict. Even local markets offered limited supplies. The

imperial government refused to forward food parcels to POWs unless they were addressed to individuals. To improve

food deliveries, the WPA devised a system to work within these regulations. American YMCA secretaries in Denmark

and Switzerland purchased food and shipped the packets to designated prisoners in Austria-Hungary. These POWs

then handed over the packages to representatives of the cooperative societies or welfare committees in each camp.

The food was then sold at cost or distributed to the most needy. The proceeds from these sales were returned to

the YMCA, and this money was used to purchase more food parcels for POWs. The cooperative societies were extremely

useful, not only in improving prison camp living standards, but in providing a meaningful outlet for a large number

of POWs with time on their hands.3

The Central Bureau in Vienna worked to maintain daily operations in the prison camps by providing supplies,

communications, and personnel as efficiently as possible. Most of the Russian, Serbian, Romanian, and Italian

prisoners were poor and lacked education. Their families did not have the resources to send packages to improve

their condition, nor could their governments extend much help. As the war dragged on and the Allied blockade of

the Central Powers became more effective, living standards for Austro-Hungarian prisoners fell drastically. By

1917, prison rations were limited to cabbage or beef soup, one-quarter loaf of black bread per day, and an

occasional small portion of meat for each prisoner. In addition, many POWs were insufficiently clad, especially

if they were captured during summer campaigning, and coal became unobtainable. The American YMCA was not set up

to conduct physical relief operations, but conditions became so bad that secretaries made every effort to assist

welfare agencies and supplement relief supplies. Because of the extensive network the American YMCA had established

in the Austro-Hungarian war prison system, the WPA became the distributing agent and cooperated with the majority

of welfare organizations such as the Russian Red Cross, the Russian Relief Fund, and Swedish relief organizations.

Austro-Hungarian regulations on purchasing food were very strict. Even local markets offered limited supplies. The

imperial government refused to forward food parcels to POWs unless they were addressed to individuals. To improve

food deliveries, the WPA devised a system to work within these regulations. American YMCA secretaries in Denmark

and Switzerland purchased food and shipped the packets to designated prisoners in Austria-Hungary. These POWs

then handed over the packages to representatives of the cooperative societies or welfare committees in each camp.

The food was then sold at cost or distributed to the most needy. The proceeds from these sales were returned to

the YMCA, and this money was used to purchase more food parcels for POWs. The cooperative societies were extremely

useful, not only in improving prison camp living standards, but in providing a meaningful outlet for a large number

of POWs with time on their hands.3

5

The American YMCA worked with other international relief agencies in providing services for Allied prisoners in

the Dual Monarchy. The Crown Princess of Sweden collected and shipped large quantities of food and clothing through

the American YMCA. Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna led the Russian Relief Fund, which collected food, clothing, and

money for Russian prisoners incarcerated in Austro-Hungarian prisons. This fund sent Liebesgaben (charity

gifts), which included items from food and clothing to religious icons. These gifts carried the imperial seal and

demonstrated the Russian imperial family's concern for prisoners. These parcels were sent through the YMCA distribution

center in Copenhagen to Austria-Hungary.

The American YMCA worked with other international relief agencies in providing services for Allied prisoners in

the Dual Monarchy. The Crown Princess of Sweden collected and shipped large quantities of food and clothing through

the American YMCA. Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna led the Russian Relief Fund, which collected food, clothing, and

money for Russian prisoners incarcerated in Austro-Hungarian prisons. This fund sent Liebesgaben (charity

gifts), which included items from food and clothing to religious icons. These gifts carried the imperial seal and

demonstrated the Russian imperial family's concern for prisoners. These parcels were sent through the YMCA distribution

center in Copenhagen to Austria-Hungary.

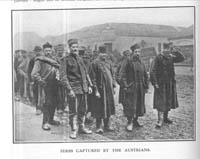

The Russian and Danish Red Crosses also conducted numerous inspection trips of prison camps in the Dual Monarchy.

The Red Cross representatives distributed funds through American YMCA secretaries. While the plight of Russian,

Italian, and Romanian POWs was great, the Serbian prisoners suffered the most. Because their country ceased to exist

after October 1915, the Serbs lost access to support from their families and their government. Association secretaries

made impassioned pleas for American citizens to donate generously to help Serbian POWs, and the International

Committee placed $20,000 in credit in Copenhagen to aid the Serbs. As YMCA workers pointed out, these POWs had no one

else to turn to, and the interned prisoners would never forget the goodwill offered by American contributors.4

The Russian and Danish Red Crosses also conducted numerous inspection trips of prison camps in the Dual Monarchy.

The Red Cross representatives distributed funds through American YMCA secretaries. While the plight of Russian,

Italian, and Romanian POWs was great, the Serbian prisoners suffered the most. Because their country ceased to exist

after October 1915, the Serbs lost access to support from their families and their government. Association secretaries

made impassioned pleas for American citizens to donate generously to help Serbian POWs, and the International

Committee placed $20,000 in credit in Copenhagen to aid the Serbs. As YMCA workers pointed out, these POWs had no one

else to turn to, and the interned prisoners would never forget the goodwill offered by American contributors.4

6

Despite these works, the combined relief efforts of the Allied governments fell far short of meeting the desperate

needs in the Dual Monarchy. The total amount of supplies available for POW relief was minuscule in comparison to

the number of war prisoners. By 1917, the Allied blockade had created famine in Central Europe, which directly

affected living standards in Dual Monarchy prison camps. The food situation became so critical that by January

1917, the Rockefeller Foundation, the International Red Cross, and the International Committee of the American

YMCA (represented by Archibald C. Harte and chaired by John R. Mott) formed the Council of Prisoners of War, with

the full approval of the State Department. The objective of this agency was to provide Allied POWs with food,

clothing, and medical supplies to supplement their daily rations to survive their imprisonment. Payment for the

supplies and the costs of transportation would be borne by the Allied government sending assistance to their

captive nationals, while the Rockefeller Foundation paid the administrative costs for the program. In addition,

funds normally dispensed by U.S. embassy officials on behalf of belligerent governments would now be distributed

by the American YMCA. Planning had proceeded to the point where the Central Powers had accepted all of the British

conditions to begin the service, and shipping and distribution networks through neutral ports had been finalized.

The relief plan collapsed, however, when the Allies decided to continue to enforce a strict blockade to force the

Central Powers to surrender, even though it meant starvation for the millions of Allied POWs in Central Europe as

well.5

Despite these works, the combined relief efforts of the Allied governments fell far short of meeting the desperate

needs in the Dual Monarchy. The total amount of supplies available for POW relief was minuscule in comparison to

the number of war prisoners. By 1917, the Allied blockade had created famine in Central Europe, which directly

affected living standards in Dual Monarchy prison camps. The food situation became so critical that by January

1917, the Rockefeller Foundation, the International Red Cross, and the International Committee of the American

YMCA (represented by Archibald C. Harte and chaired by John R. Mott) formed the Council of Prisoners of War, with

the full approval of the State Department. The objective of this agency was to provide Allied POWs with food,

clothing, and medical supplies to supplement their daily rations to survive their imprisonment. Payment for the

supplies and the costs of transportation would be borne by the Allied government sending assistance to their

captive nationals, while the Rockefeller Foundation paid the administrative costs for the program. In addition,

funds normally dispensed by U.S. embassy officials on behalf of belligerent governments would now be distributed

by the American YMCA. Planning had proceeded to the point where the Central Powers had accepted all of the British

conditions to begin the service, and shipping and distribution networks through neutral ports had been finalized.

The relief plan collapsed, however, when the Allies decided to continue to enforce a strict blockade to force the

Central Powers to surrender, even though it meant starvation for the millions of Allied POWs in Central Europe as

well.5

7

The Central Bureau also became a clearinghouse for information about war prisoners in the Dual Monarchy that the

organization shared with other WPAs in other countries. In Austria-Hungary, the Central Bureau worked with the

Austro-Hungarian Red Cross and the Austrian and Hungarian national YMCA movements to help families contact loved

ones in captivity. By exchanging data with WPA organizations in other countries, the American YMCA was able to

provide a variety of services.

The Central Bureau also became a clearinghouse for information about war prisoners in the Dual Monarchy that the

organization shared with other WPAs in other countries. In Austria-Hungary, the Central Bureau worked with the

Austro-Hungarian Red Cross and the Austrian and Hungarian national YMCA movements to help families contact loved

ones in captivity. By exchanging data with WPA organizations in other countries, the American YMCA was able to

provide a variety of services.

The Association tracked down lost family members who were reported missing or lost and provided prisoners with

news from home; it also transferred money to prisoners in Allied camps to help improve their living standards.

This POW information bureau became very important for families in Austria-Hungary with relatives in Russian prison

camps, easing family suffering by providing them with information about the health and location of their relatives.

For the prisoners, contact with home helped reduce their homesickness and improved their outlook on life. The Vienna

office worked with several POW organizations, such as the Association of the Families of Krasnoyarsk War Prisoners,

to help incarcerated family members through the Association's WPA central office in Petrograd.6

The Association tracked down lost family members who were reported missing or lost and provided prisoners with

news from home; it also transferred money to prisoners in Allied camps to help improve their living standards.

This POW information bureau became very important for families in Austria-Hungary with relatives in Russian prison

camps, easing family suffering by providing them with information about the health and location of their relatives.

For the prisoners, contact with home helped reduce their homesickness and improved their outlook on life. The Vienna

office worked with several POW organizations, such as the Association of the Families of Krasnoyarsk War Prisoners,

to help incarcerated family members through the Association's WPA central office in Petrograd.6

8

With the establishment of official American YMCA relations with the Habsburg government, the International

Committee in New York sent secretaries to Austria-Hungary to provide the personnel to conduct the POW program.

After the initial Ministry of War agreement to begin operations in two prison camps, reciprocal diplomacy required

the introduction of additional secretaries for the Russian, Serbian, Italian, and Romanian POWs. Because Dual

Monarchy resources were already stretched thinly by wartime mobilization and the continuing influx of Allied

prisoners, Austro-Hungarian authorities soon recognized the value of an American social welfare organization

providing relief for POWs. By December 1915, the Ministry of War extended American YMCA access to six additional

prison camps and agreed to admit four additional neutral secretaries on the basis of reciprocity. By February

1916, the Ministry of War had permitted the establishment of five more YMCA huts, for a total of thirteen, and

agreed to admit nine new neutral secretaries, for a total of thirteen field secretaries. As a result, the

International Committee had to scramble to find qualified volunteers to work in the POW field. To be qualified,

a volunteer needed a background in the Association program and leadership experience, plus knowledge of German

or Hungarian (to communicate with prison officials) and Russian, Serbian, Italian, or Romanian (to work with the

prisoners). The language requirement severely restricted the pool of available secretaries.7

With the establishment of official American YMCA relations with the Habsburg government, the International

Committee in New York sent secretaries to Austria-Hungary to provide the personnel to conduct the POW program.

After the initial Ministry of War agreement to begin operations in two prison camps, reciprocal diplomacy required

the introduction of additional secretaries for the Russian, Serbian, Italian, and Romanian POWs. Because Dual

Monarchy resources were already stretched thinly by wartime mobilization and the continuing influx of Allied

prisoners, Austro-Hungarian authorities soon recognized the value of an American social welfare organization

providing relief for POWs. By December 1915, the Ministry of War extended American YMCA access to six additional

prison camps and agreed to admit four additional neutral secretaries on the basis of reciprocity. By February

1916, the Ministry of War had permitted the establishment of five more YMCA huts, for a total of thirteen, and

agreed to admit nine new neutral secretaries, for a total of thirteen field secretaries. As a result, the

International Committee had to scramble to find qualified volunteers to work in the POW field. To be qualified,

a volunteer needed a background in the Association program and leadership experience, plus knowledge of German

or Hungarian (to communicate with prison officials) and Russian, Serbian, Italian, or Romanian (to work with the

prisoners). The language requirement severely restricted the pool of available secretaries.7

9

Braunau-in-Böhmen in Bohemia was the first camp the Austro-Hungarian authorities opened to YMCA workers

and the site of the first Association hut in a prison camp in the Dual Monarchy. This prison housed mostly Russian

POWs, although many Serbs were also incarcerated in Braunau. The Ministry of War granted permission to begin

operations on 11 June 1915, but the development of the WPA program was slow. Due to the lack of skilled workers

among the prisoners, construction of the Association hall was delayed. On 19 December 1915, Professor Karl Wilz-Oberlin,

president of the Austrian National YMCA Alliance, finally dedicated the opening of the Stokes Pavilion (named after James Stokes, the American benefactor who paid for the facility's construction) with Phildius and other

important dignitaries in attendance. Although the building was finished, the first secretary to undertake regular

welfare work, Penningroth, did not start until March 1916. Penningroth conducted operations for four months until

he was reassigned to the WPA Office in Vienna; he was replaced by Clarence W. Bartz who administered Red Triangle

programs from October 1916 until April 1917. The American YMCA developed an extensive program for the inmates.

Penningroth emphasized the musical program. They purchased musical instruments and obtained supplies for prisoners

to construct instruments so that the inmates could form an orchestra and a band. Bartz expanded the program after

he obtained a gramophone; he introduced concerts for the invalid prisoners recovering in the prison hospital. Through

this work, they improved morale and provided entertainment.8

Braunau-in-Böhmen in Bohemia was the first camp the Austro-Hungarian authorities opened to YMCA workers

and the site of the first Association hut in a prison camp in the Dual Monarchy. This prison housed mostly Russian

POWs, although many Serbs were also incarcerated in Braunau. The Ministry of War granted permission to begin

operations on 11 June 1915, but the development of the WPA program was slow. Due to the lack of skilled workers

among the prisoners, construction of the Association hall was delayed. On 19 December 1915, Professor Karl Wilz-Oberlin,

president of the Austrian National YMCA Alliance, finally dedicated the opening of the Stokes Pavilion (named after James Stokes, the American benefactor who paid for the facility's construction) with Phildius and other

important dignitaries in attendance. Although the building was finished, the first secretary to undertake regular

welfare work, Penningroth, did not start until March 1916. Penningroth conducted operations for four months until

he was reassigned to the WPA Office in Vienna; he was replaced by Clarence W. Bartz who administered Red Triangle

programs from October 1916 until April 1917. The American YMCA developed an extensive program for the inmates.

Penningroth emphasized the musical program. They purchased musical instruments and obtained supplies for prisoners

to construct instruments so that the inmates could form an orchestra and a band. Bartz expanded the program after

he obtained a gramophone; he introduced concerts for the invalid prisoners recovering in the prison hospital. Through

this work, they improved morale and provided entertainment.8

10

The American secretaries also emphasized other aspects of the Association program. Penningroth set up an invalid

school where maimed POWs learned to use their new artificial limbs. More importantly, the school taught them a

new trade so they could support themselves after they returned home. The Americans established a school in the

hospital, offering elementary lessons in reading and writing. They also distributed food, books, and pictures to

lift spirits and encourage the wounded to think about the future. The secretaries acquired books to stock the

library in the Stokes Pavilion, and organized a dramatic club and theater group.

The American secretaries also emphasized other aspects of the Association program. Penningroth set up an invalid

school where maimed POWs learned to use their new artificial limbs. More importantly, the school taught them a

new trade so they could support themselves after they returned home. The Americans established a school in the

hospital, offering elementary lessons in reading and writing. They also distributed food, books, and pictures to

lift spirits and encourage the wounded to think about the future. The secretaries acquired books to stock the

library in the Stokes Pavilion, and organized a dramatic club and theater group.

The establishment of a gymnasium helped improve the physical condition of the POWs. The hut also served a religious

role, as the Austro-Hungarian Feldkurat (military chaplain department) provided services on Sundays and

holidays. The secretaries also organized welfare committees among the POWs, which provided an important

infrastructure for supporting the Association program. The prisoners supervised the distribution of food

parcels and other materials, maintained the school and equipment, and alerted the secretaries to POWs suffering

from morale problems, especially homesickness.9

The establishment of a gymnasium helped improve the physical condition of the POWs. The hut also served a religious

role, as the Austro-Hungarian Feldkurat (military chaplain department) provided services on Sundays and

holidays. The secretaries also organized welfare committees among the POWs, which provided an important

infrastructure for supporting the Association program. The prisoners supervised the distribution of food

parcels and other materials, maintained the school and equipment, and alerted the secretaries to POWs suffering

from morale problems, especially homesickness.9

11

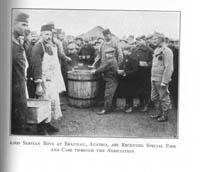

The most important work provided by the American YMCA at Braunau-in-Böhmen was its program for the boys

interned in the camp. As discussed earlier, many Russian and Serbian sons followed their fathers into the army

when they were mobilized in 1914. American secretaries found 1,500 boys between the ages of eight and seventeen

at Braunau dispersed among the general prison population, without special facilities provided for their well-being

and education. Penningroth initially provided a large room in the Stokes Pavilion for their education, and the

Feldkurat agreed to begin religious instruction for the boys. The Association hut could not, however, accommodate

all of the boys. Penningroth made a proposal that included a diagram to John R. Mott for the American YMCA to

establish a Boys' Home in Braunau (he estimated the cost would be as little as six cents per boy per day). The

Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War supported the proposal, and the International Committee approved the construction

of a ten-room schoolhouse.10

The most important work provided by the American YMCA at Braunau-in-Böhmen was its program for the boys

interned in the camp. As discussed earlier, many Russian and Serbian sons followed their fathers into the army

when they were mobilized in 1914. American secretaries found 1,500 boys between the ages of eight and seventeen

at Braunau dispersed among the general prison population, without special facilities provided for their well-being

and education. Penningroth initially provided a large room in the Stokes Pavilion for their education, and the

Feldkurat agreed to begin religious instruction for the boys. The Association hut could not, however, accommodate

all of the boys. Penningroth made a proposal that included a diagram to John R. Mott for the American YMCA to

establish a Boys' Home in Braunau (he estimated the cost would be as little as six cents per boy per day). The

Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War supported the proposal, and the International Committee approved the construction

of a ten-room schoolhouse.10

12

The War Ministry reserved eight barracks for dormitories, eating halls, and workshops for the boys. The camp

commandant segregated the Russian and Serbian boys from the main prison camp population and Bartz introduced an

extensive educational program. They attended other Association functions, such as theater performances, concerts,

and movies. Most importantly, secretaries sought to train these boys for the future. The boys learned a trade,

such as shoe-making, sewing, or carpentry. The Ministry of War set aside two acres of land for agricultural

instruction. Each boy had a plot of land to raise a garden and rabbits, under the supervision of an agricultural

expert. This program also expanded the prison's dwindling food supplies. Penningroth also set up an invalid school

for boys who had been maimed. This work was so successful that the American YMCA introduced similar services for

boys in Wieselburg and Nezsider in 1917. By relieving these boys of the boredom of prison life, educating them,

and teaching them a trade, the American YMCA hoped to make them more prosperous subjects and establish the foundations

of good-will for Association expansion into their countries after the war.11

The War Ministry reserved eight barracks for dormitories, eating halls, and workshops for the boys. The camp

commandant segregated the Russian and Serbian boys from the main prison camp population and Bartz introduced an

extensive educational program. They attended other Association functions, such as theater performances, concerts,

and movies. Most importantly, secretaries sought to train these boys for the future. The boys learned a trade,

such as shoe-making, sewing, or carpentry. The Ministry of War set aside two acres of land for agricultural

instruction. Each boy had a plot of land to raise a garden and rabbits, under the supervision of an agricultural

expert. This program also expanded the prison's dwindling food supplies. Penningroth also set up an invalid school

for boys who had been maimed. This work was so successful that the American YMCA introduced similar services for

boys in Wieselburg and Nezsider in 1917. By relieving these boys of the boredom of prison life, educating them,

and teaching them a trade, the American YMCA hoped to make them more prosperous subjects and establish the foundations

of good-will for Association expansion into their countries after the war.11

13

The Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War gave permission for the YMCA to begin POW operations in Sopronnyek in Hungary

on 5 August 1915. Like Braunau-in-Böhmen, this camp had a predominantly Russian prison population. The American

YMCA provided funding for the construction of an Association hut, which was delayed due to the scarcity of skilled

prisoner labor. The official building inauguration was celebrated with great fanfare in December 1915. Jean Schoop

supervised POW operations after he arrived in July 1916, and remained attached to the camp until the end of the

war.12

The Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War gave permission for the YMCA to begin POW operations in Sopronnyek in Hungary

on 5 August 1915. Like Braunau-in-Böhmen, this camp had a predominantly Russian prison population. The American

YMCA provided funding for the construction of an Association hut, which was delayed due to the scarcity of skilled

prisoner labor. The official building inauguration was celebrated with great fanfare in December 1915. Jean Schoop

supervised POW operations after he arrived in July 1916, and remained attached to the camp until the end of the

war.12

14

During 1915, the Ministry of War also approved the introduction of Association services at Prague and at

Brunn-am-Gebirge, Spratzern, and Wieselburg in Lower Austria. The government extended permission to enter Prague

and Brunn on May 8, and to begin work in the other two camps on December 14. Theodore F. Schroeder was one of the

first two American secretaries to arrive in Austria-Hungary, and he began work in Spratzern in March 1916. He

brought a soccer ball as part of his equipment, and found it very useful in helping wounded POWs recover as a

means of physical therapy.

During 1915, the Ministry of War also approved the introduction of Association services at Prague and at

Brunn-am-Gebirge, Spratzern, and Wieselburg in Lower Austria. The government extended permission to enter Prague

and Brunn on May 8, and to begin work in the other two camps on December 14. Theodore F. Schroeder was one of the

first two American secretaries to arrive in Austria-Hungary, and he began work in Spratzern in March 1916. He

brought a soccer ball as part of his equipment, and found it very useful in helping wounded POWs recover as a

means of physical therapy.

Soon crippled prisoners competed in soccer games before hundreds of convalescing POWs. Schroeder also introduced

musical entertainment for bedridden prisoners. He arranged gramophone concerts with the assistance of a Russian

prisoner, who carried the equipment. The YMCA also provided material for classes in reading, writing, and geography,

as Schroeder found that most of the prisoners were illiterate. To help the POWs find better employment after the war,

Schroeder set up woodcarving and bookbinding classes. The "Y" also sent the POWs at Spratzern playground equipment,

which included games such as Russian bowling, croquette, and horseshoes, to help prisoners pass away their idle hours.

Another American secretary, Gustav J. Kaletsch, arrived at Spratzern in February 1917 and served at the camp for two

months.13

Soon crippled prisoners competed in soccer games before hundreds of convalescing POWs. Schroeder also introduced

musical entertainment for bedridden prisoners. He arranged gramophone concerts with the assistance of a Russian

prisoner, who carried the equipment. The YMCA also provided material for classes in reading, writing, and geography,

as Schroeder found that most of the prisoners were illiterate. To help the POWs find better employment after the war,

Schroeder set up woodcarving and bookbinding classes. The "Y" also sent the POWs at Spratzern playground equipment,

which included games such as Russian bowling, croquette, and horseshoes, to help prisoners pass away their idle hours.

Another American secretary, Gustav J. Kaletsch, arrived at Spratzern in February 1917 and served at the camp for two

months.13

15

The prison camp at Wieselburg was one of the largest concentration camps in Austria, housing over seventy thousand men

in seven hundred buildings. Hecker began service at Wieselburg in March 1916, and found working in the camp rewarding.

The prison authorities welcomed the American secretary and provided the Association with several barracks and

a budget of six thousand Kronen ($800). This allowed Hecker to adapt and equip several barracks for Association

functions; he set up a church (forty meters by ten meters), which included two small rooms for prayer and

meditation.

The prison camp at Wieselburg was one of the largest concentration camps in Austria, housing over seventy thousand men

in seven hundred buildings. Hecker began service at Wieselburg in March 1916, and found working in the camp rewarding.

The prison authorities welcomed the American secretary and provided the Association with several barracks and

a budget of six thousand Kronen ($800). This allowed Hecker to adapt and equip several barracks for Association

functions; he set up a church (forty meters by ten meters), which included two small rooms for prayer and

meditation.

The prisoners modified a large barrack to include a theater, lecture hall, concert hall, school, and library. A

third barrack became a cinema after the arrival of a movie projector for educational and entertainment purposes.

This barrack was also used by the camp's non-Christian population with the consent of the Christian and non-Christian

POWs. With such a large infrastructure, Hecker developed an extensive Association program. The dramatic society

staged high-quality productions with the support of the camp's orchestra.

The prisoners modified a large barrack to include a theater, lecture hall, concert hall, school, and library. A

third barrack became a cinema after the arrival of a movie projector for educational and entertainment purposes.

This barrack was also used by the camp's non-Christian population with the consent of the Christian and non-Christian

POWs. With such a large infrastructure, Hecker developed an extensive Association program. The dramatic society

staged high-quality productions with the support of the camp's orchestra.

Hecker also organized two libraries-one for the guards to relieve their boredom, and the other for the prisoners.

He purchased Russian, Polish, Hebrew, and German books in Berlin and Vienna to stock the libraries, although there

was always a shortage of Russian texts. Some prisoners even donated their own private books to the general collection.

To ease the Russian book shortage, Hecker arranged for the prisoners to produce reprints. This program was especially

important, since almost 90 percent of the camp's inmate population temporarily left the prison for work assignments,

and they demanded literature for diversion away from the camp. After a book was approved by the camp censor, the

POWs could produce a thirty-two-page pamphlet at a cost of six hundred Kronen for ten thousand copies. Hecker arranged to have

these printings distributed to other prison camps in Germany and Austria-Hungary to help alleviate the book

shortage.14

Hecker also organized two libraries-one for the guards to relieve their boredom, and the other for the prisoners.

He purchased Russian, Polish, Hebrew, and German books in Berlin and Vienna to stock the libraries, although there

was always a shortage of Russian texts. Some prisoners even donated their own private books to the general collection.

To ease the Russian book shortage, Hecker arranged for the prisoners to produce reprints. This program was especially

important, since almost 90 percent of the camp's inmate population temporarily left the prison for work assignments,

and they demanded literature for diversion away from the camp. After a book was approved by the camp censor, the

POWs could produce a thirty-two-page pamphlet at a cost of six hundred Kronen for ten thousand copies. Hecker arranged to have

these printings distributed to other prison camps in Germany and Austria-Hungary to help alleviate the book

shortage.14

16

The prison camp at Wieselburg provided extensive medical services through numerous hospitals and invalid wards

for Allied prisoners. Over five thousand POWs in this camp suffered from wounds or illness, and Hecker organized a

welfare committee to render assistance. This committee listed prisoners who did not receive help from home and

could not work, and the YMCA focused their limited resources on these men. Hecker praised the Austro-Hungarian

authorities for their work in fitting amputees with artificial limbs.

The prison camp at Wieselburg provided extensive medical services through numerous hospitals and invalid wards

for Allied prisoners. Over five thousand POWs in this camp suffered from wounds or illness, and Hecker organized a

welfare committee to render assistance. This committee listed prisoners who did not receive help from home and

could not work, and the YMCA focused their limited resources on these men. Hecker praised the Austro-Hungarian

authorities for their work in fitting amputees with artificial limbs.

They built a shop to produce limbs, and outfitted a therapeutic hospital with modern equipment for physical

therapy. Dr. Duschak, the chief physician in the trauma department, was a dedicated doctor and worked well with

Hecker. The American YMCA provided him with tonics and special drugs. Hecker also worked with Duschak to organize

invalid schools where wounded prisoners could learn new trades. Most invalids remained idle, and their condition

gradually deteriorated. They were potentially an army of paupers and idlers who would become a strain on their

home communities after the end of the war. Through American YMCA funding, wounded soldiers learned new skills

and professions and were prepared to return home ready to resume their roles as family providers.

They built a shop to produce limbs, and outfitted a therapeutic hospital with modern equipment for physical

therapy. Dr. Duschak, the chief physician in the trauma department, was a dedicated doctor and worked well with

Hecker. The American YMCA provided him with tonics and special drugs. Hecker also worked with Duschak to organize

invalid schools where wounded prisoners could learn new trades. Most invalids remained idle, and their condition

gradually deteriorated. They were potentially an army of paupers and idlers who would become a strain on their

home communities after the end of the war. Through American YMCA funding, wounded soldiers learned new skills

and professions and were prepared to return home ready to resume their roles as family providers.

17

Hecker was convinced that service to invalids was the greatest moral and social service the YMCA could render.

The major obstacle was finding teachers to staff the invalid school. Hecker found sixteen educators among

the POW population, and then surveyed the condition and education levels of the wounded students. An Austro-Hungarian

officer provided barracks for the school, and the American YMCA funded the program and obtained the necessary

equipment such as benches, machines, and tools for the training program. Hecker began the program with a budget

of two thousand Kronen, and American contributors sent additional aid. As Hecker pointed out, for a few thousand

dollars the YMCA could teach thousands of invalids useful occupations and save them from physical and moral

degradation. Hecker's project was so successful that the Austro-Hungarian authorities asked him to visit an invalid

institution for wounded Austro-Hungarian soldiers in Vienna. In addition, Hecker helped organize and raise funds for

a consumptive hospital in Wieselburg. An Austrian reserve officer-a friend of the YMCA-contributed the initial three thousand Kronen, and American contributors augmented the total.15

Hecker was convinced that service to invalids was the greatest moral and social service the YMCA could render.

The major obstacle was finding teachers to staff the invalid school. Hecker found sixteen educators among

the POW population, and then surveyed the condition and education levels of the wounded students. An Austro-Hungarian

officer provided barracks for the school, and the American YMCA funded the program and obtained the necessary

equipment such as benches, machines, and tools for the training program. Hecker began the program with a budget

of two thousand Kronen, and American contributors sent additional aid. As Hecker pointed out, for a few thousand

dollars the YMCA could teach thousands of invalids useful occupations and save them from physical and moral

degradation. Hecker's project was so successful that the Austro-Hungarian authorities asked him to visit an invalid

institution for wounded Austro-Hungarian soldiers in Vienna. In addition, Hecker helped organize and raise funds for

a consumptive hospital in Wieselburg. An Austrian reserve officer-a friend of the YMCA-contributed the initial three thousand Kronen, and American contributors augmented the total.15

18

Like Braunau-in-Böhmen, Wieselburg had a large number of boys in the general prison population. Hecker

assumed charge of the boys between twelve and seventeen. The prison authorities provided two reconstructed barracks,

while the YMCA organized a school and apprenticeship program for their training. The War Ministry decided to make

Wieselburg the primary center for young Russian POWs. Boys under the age of sixteen interned in other camps in the

Dual Monarchy were reassigned to Wieselburg. The camp commandant made Hecker the sole supervisor for the Boys'

Department, with full responsibility for their education and living arrangements. The American YMCA funded

the program and expanded the facility to include sleeping apartments, dining rooms, a gymnasium, and workshops.

Hecker also extended YMCA services to Nezsider in February 1917, including the program for boys.16

Like Braunau-in-Böhmen, Wieselburg had a large number of boys in the general prison population. Hecker

assumed charge of the boys between twelve and seventeen. The prison authorities provided two reconstructed barracks,

while the YMCA organized a school and apprenticeship program for their training. The War Ministry decided to make

Wieselburg the primary center for young Russian POWs. Boys under the age of sixteen interned in other camps in the

Dual Monarchy were reassigned to Wieselburg. The camp commandant made Hecker the sole supervisor for the Boys'

Department, with full responsibility for their education and living arrangements. The American YMCA funded

the program and expanded the facility to include sleeping apartments, dining rooms, a gymnasium, and workshops.

Hecker also extended YMCA services to Nezsider in February 1917, including the program for boys.16

19

By March 1916, American secretaries had begun POW operations in three more prison camps including Hart, in

Upper Austria, as well as Purgstall and Neulengbach in Lower Austria. Hecker introduced a full YMCA program

at Purgstall, a camp full of Russian prisoners, while Schroeder began operations in Neulengbach. Schroeder

was eventually replaced by Kaletsch, who started work in the prison camp by February 1917, for a two-month

period. Through the American YMCA, the camp received instruments for a full band, and the secretary organized

a chorus.

By March 1916, American secretaries had begun POW operations in three more prison camps including Hart, in

Upper Austria, as well as Purgstall and Neulengbach in Lower Austria. Hecker introduced a full YMCA program

at Purgstall, a camp full of Russian prisoners, while Schroeder began operations in Neulengbach. Schroeder

was eventually replaced by Kaletsch, who started work in the prison camp by February 1917, for a two-month

period. Through the American YMCA, the camp received instruments for a full band, and the secretary organized

a chorus.

By January 1917, additional barracks were opened for YMCA activities, including a special Christmas celebration.

Hecker also established an Association POW program at Hart. In the beginning, the Austro-Hungarian camp

administration did not pay too much attention to the secretary's work. Because there had been a dearth of

educational and social work in the prison before he arrived, Hecker had immediate POW support. He obtained

and rebuilt a large barracks (thirty-five feet by one hundred-fifty feet) within the confines of the prison,

as well as a special barrack in the hospital. The American secretary found equipment for these facilities and

was able to set up the program at a cost of six thousand Kronen. With time and experience, both the camp

administrators and prisoners came to appreciate and take pride in their Association.

By January 1917, additional barracks were opened for YMCA activities, including a special Christmas celebration.

Hecker also established an Association POW program at Hart. In the beginning, the Austro-Hungarian camp

administration did not pay too much attention to the secretary's work. Because there had been a dearth of

educational and social work in the prison before he arrived, Hecker had immediate POW support. He obtained

and rebuilt a large barracks (thirty-five feet by one hundred-fifty feet) within the confines of the prison,

as well as a special barrack in the hospital. The American secretary found equipment for these facilities and

was able to set up the program at a cost of six thousand Kronen. With time and experience, both the camp

administrators and prisoners came to appreciate and take pride in their Association.

The main hut was dedicated on 15 August 1916, with visitors from the Austro-Hungarian Red Cross and staff officers

from the imperial army in attendance. The prisoners made moving speeches at the inauguration, talking about their

two years of monotony behind barbed wire. They were slowly dying of spiritual and physical attrition. They planned

revenge against their guards as well as escape plans. When life seemed darkest, the Americans arrived as "heavenly

messengers," and life in the camp changed. They forgot their sorrows and bitterness, and began building a bridge

of mutual accommodation, if not appreciation, between the prisoners and the guards. This was a moving testament

to the high value of the Association's POW work. As in Wieselburg, Hecker found a large number of boys in the

prison camp at Hart. He arranged to segregate them from the general prison population, and set up a special YMCA

school for their education.17

The main hut was dedicated on 15 August 1916, with visitors from the Austro-Hungarian Red Cross and staff officers

from the imperial army in attendance. The prisoners made moving speeches at the inauguration, talking about their

two years of monotony behind barbed wire. They were slowly dying of spiritual and physical attrition. They planned

revenge against their guards as well as escape plans. When life seemed darkest, the Americans arrived as "heavenly

messengers," and life in the camp changed. They forgot their sorrows and bitterness, and began building a bridge

of mutual accommodation, if not appreciation, between the prisoners and the guards. This was a moving testament

to the high value of the Association's POW work. As in Wieselburg, Hecker found a large number of boys in the

prison camp at Hart. He arranged to segregate them from the general prison population, and set up a special YMCA

school for their education.17

20 At Neulengbach, a prison with a predominantly Russian POW population, Schroeder found a difficult situation. The prison was divided into six separate divisions, and he had to duplicate YMCA programs for each group. The Association barrack became the center of the POW program, and the commandant made unused barracks available for Association activities. The YMCA hut was used for religious services, and Schroeder worked with the Feldkurat to distribute one thousand Gospels, crosses, and icons.

21

The secretary also developed a school system. The first school was set up in the prison hospital, where POWs learned

to read and write Russian and German. Advanced classes included arithmetic, woodcarving, and geography. Schroeder

recruited teachers from among the Russian prisoners. The education program emphasized teaching wounded POWs who had

lost their right arms to learn to write with their left hands. The secretary also set up a school in the main prison

camp; the first students were prospective bakers, shoemakers, and tailors. To support these classes, Schroeder set

up a library system whereby Russian books that the secretary received could be distributed to each prison group

through a central library. For physical work, Schroeder had simple gymnastic equipment (parallel and horizontal

bars as well as rings) installed, and provided games including croquet and Russian bowling. He taught the POWs group

games to get them in better shape and help them spend their leisure hours more profitably. To provide some entertainment

for the inmates, Schroeder acquired some musical instruments and organized a brass band. The band played at theatrical

performances, concerts, and funeral services. Kaletsch replaced Schroeder in February and assumed supervision of POW

relief programs at Neulengbach for the next two months.18

The secretary also developed a school system. The first school was set up in the prison hospital, where POWs learned

to read and write Russian and German. Advanced classes included arithmetic, woodcarving, and geography. Schroeder

recruited teachers from among the Russian prisoners. The education program emphasized teaching wounded POWs who had

lost their right arms to learn to write with their left hands. The secretary also set up a school in the main prison

camp; the first students were prospective bakers, shoemakers, and tailors. To support these classes, Schroeder set

up a library system whereby Russian books that the secretary received could be distributed to each prison group

through a central library. For physical work, Schroeder had simple gymnastic equipment (parallel and horizontal

bars as well as rings) installed, and provided games including croquet and Russian bowling. He taught the POWs group

games to get them in better shape and help them spend their leisure hours more profitably. To provide some entertainment

for the inmates, Schroeder acquired some musical instruments and organized a brass band. The band played at theatrical

performances, concerts, and funeral services. Kaletsch replaced Schroeder in February and assumed supervision of POW

relief programs at Neulengbach for the next two months.18

22

The YMCA introduced WPA operations at Braunau-am-Inn in Upper Austria in October 1916 when Amos A. Ebersole,

an American WPA secretary, arrived at the camp. Braunau was a large prison camp, housing almost thirty-five thousand Russian,

Italian, and Serbian prisoners of war. Tegelbjaerg assisted Ebersole in November 1916 in developing the Red

Triangle program in the facility. Ebersole believed his most important contribution to the morale of the prison

camp was the Christmas celebrations, a difficult time for men separated from their families. He served at Braunau

until April 1917 when he left the Dual Monarchy with the other American secretaries.19

The YMCA introduced WPA operations at Braunau-am-Inn in Upper Austria in October 1916 when Amos A. Ebersole,

an American WPA secretary, arrived at the camp. Braunau was a large prison camp, housing almost thirty-five thousand Russian,

Italian, and Serbian prisoners of war. Tegelbjaerg assisted Ebersole in November 1916 in developing the Red

Triangle program in the facility. Ebersole believed his most important contribution to the morale of the prison

camp was the Christmas celebrations, a difficult time for men separated from their families. He served at Braunau

until April 1917 when he left the Dual Monarchy with the other American secretaries.19

23 After negotiations with the Italians, the American YMCA quickly set up POW operations in Mauthausen in Upper Austria. The bulk of the inmates were Italian prisoners, whose totals reached twenty thousand in early 1916. The impetus behind the introduction of Association services was the spread of rumors in Italy about the terrible conditions in Austro-Hungarian prison camps. The Italian government requested that a U.S. official conduct an investigation, and Ambassador Frederic Penfield visited the camp to assess the situation. His report did not reveal any atrocities, but he recommended that the Italian and Austro-Hungarian governments come to an agreement regarding YMCA POW services in the prison camps of both countries. The American YMCA agreed to construct a hut in Mauthausen, and Eberhard Phildius, the son of Christian Phildius, arrived in May 1916 to begin POW operations. He was eventually replaced by an American secretary, Roy Alvan Welker, by January 1917, who remained until April 1917. As in other prison camps, these secretaries set up an extensive educational system with a wide variety of courses. Due to the large number of college students among the Italian prisoners, the YMCA was able to offer university extension classes at Mauthausen. During his inspection trip, Ambassador Penfield also recommended that the American YMCA construct a hut at Katzenau, where fifty thousand Italian civilians were interned. The Association agreed, and arranged with the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War to begin operations by July 1916.20

American YMCA Operations in Hungary

24

American Association work in Hungarian prison camps expanded tremendously from July to November 1916. Secretaries

began operations in seven prisons in July, one camp in September, and another by November. Raymond J. Reitzel

began work at Zalägerszeg in July 1916, a prison camp filled with Russian POWs. He found the Austro-Hungarian

officers very sympathetic and liberal, which allowed him to establish an extensive POW program. Camp officials

allowed prisoners (with special permission) to go out into the fields or factories without guards to learn a

trade. Protestant and Catholic POWs attended church services on Sundays outside of camp. Reitzel developed a

full Association POW program at Zalägerszeg.

American Association work in Hungarian prison camps expanded tremendously from July to November 1916. Secretaries

began operations in seven prisons in July, one camp in September, and another by November. Raymond J. Reitzel

began work at Zalägerszeg in July 1916, a prison camp filled with Russian POWs. He found the Austro-Hungarian

officers very sympathetic and liberal, which allowed him to establish an extensive POW program. Camp officials

allowed prisoners (with special permission) to go out into the fields or factories without guards to learn a

trade. Protestant and Catholic POWs attended church services on Sundays outside of camp. Reitzel developed a

full Association POW program at Zalägerszeg.

In the YMCA barrack, the secretary set up classes for both elementary and advanced students. The Commissary Group

organized an alphabet school to teach illiterate POWs simple reading and writing, plus a class for elementary

drawing. For more advanced students, classes in painting and drawing started, with the Association providing the

materials. Reitzel found three instructors, who began classes in music, languages, and science. Russian officers

in particular were very interested in furthering their educations. The secretary also set up a reading and writing

school for the officers' orderlies, which included almost one hundred men. Over time, Reitzel gradually assembled

a library, which was run by the POWs. In addition, he set up an elementary school in the prison hospital to teach

wounded and sick POWs reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reitzel was eventually able to expand the classes to more

advanced levels.21

In the YMCA barrack, the secretary set up classes for both elementary and advanced students. The Commissary Group

organized an alphabet school to teach illiterate POWs simple reading and writing, plus a class for elementary

drawing. For more advanced students, classes in painting and drawing started, with the Association providing the

materials. Reitzel found three instructors, who began classes in music, languages, and science. Russian officers

in particular were very interested in furthering their educations. The secretary also set up a reading and writing

school for the officers' orderlies, which included almost one hundred men. Over time, Reitzel gradually assembled

a library, which was run by the POWs. In addition, he set up an elementary school in the prison hospital to teach

wounded and sick POWs reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reitzel was eventually able to expand the classes to more

advanced levels.21

25

For the physical side of the Association program, Reitzel organized soccer and other sport matches, which

drew large crowds of spectators. He also developed a religious program with the support of the Austro-Hungarian

Feldkurat, which provided a chaplain. They distributed Russian crosses and icons among the POWs and to

members of work parties. Most of the internees in this camp were Russian Orthodox. Reitzel arranged for a separate

barrack to be converted into a place of worship; the prisoners constructed a fine wooden altar with icons for

their devotional services. Reitzel developed the social side of the Association program as well. He organized

a string orchestra in the main camp that gave concerts, both to the general population and in the camp hospital.

Reitzel also formed a chorus, with music and instruments provided by the American YMCA. He even found a piano,

which he placed at the disposal of a Moscow opera singer who then taught music and assisted with the concert

program. For entertainment in the hospital, Reitzel provided a gramophone and a small portable kinescope; prison

officials placed a large hall at the secretary's disposal two times a week for performances. For inmates too sick

to move, Reitzel organized concerts and kinescope shows for their barracks. He also distributed a large number

of games throughout the wards to help the prisoners pass the time during their convalescence.22

For the physical side of the Association program, Reitzel organized soccer and other sport matches, which

drew large crowds of spectators. He also developed a religious program with the support of the Austro-Hungarian

Feldkurat, which provided a chaplain. They distributed Russian crosses and icons among the POWs and to

members of work parties. Most of the internees in this camp were Russian Orthodox. Reitzel arranged for a separate

barrack to be converted into a place of worship; the prisoners constructed a fine wooden altar with icons for

their devotional services. Reitzel developed the social side of the Association program as well. He organized

a string orchestra in the main camp that gave concerts, both to the general population and in the camp hospital.

Reitzel also formed a chorus, with music and instruments provided by the American YMCA. He even found a piano,

which he placed at the disposal of a Moscow opera singer who then taught music and assisted with the concert

program. For entertainment in the hospital, Reitzel provided a gramophone and a small portable kinescope; prison

officials placed a large hall at the secretary's disposal two times a week for performances. For inmates too sick

to move, Reitzel organized concerts and kinescope shows for their barracks. He also distributed a large number

of games throughout the wards to help the prisoners pass the time during their convalescence.22

26

Reitzel also imported the American concept of developing self-help groups to help alleviate welfare problems

in the camp. He set up a camp "cabinet," which served as the POWs' administrative agency, and then organized

committees to address specific issues. The emphasis of this social relief program was on prisoners' aiding

their comrades through their period of confinement. Organized as the "Russian One Year's Volunteers," the POWs

adopted policies and implemented changes that improved living conditions in the camp. One committee focused on

expanding relief work in the hospitals, especially for the critically ill. They worked in conjunction with the

regimental physician to improve conditions, and Reitzel supported their work by providing supplies and equipment,

including musical instruments. Through this self-help program, prisoners avoided boredom and inactivity and

channeled their interests and energies in a positive direction. From Reitzel's perspective, this relief work

had particular rewards for the Association. Not only would Russian prisoners return home after the war with a

warm spot for the YMCA in their hearts, which would lay the basis for postwar Association expansion, but several

of these men indicated their interest in becoming YMCA secretaries after the war. By recruiting native secretaries,

the Association would gain a tremendous advantage in developing future organizations in Russia once the fighting

ended.23

Reitzel also imported the American concept of developing self-help groups to help alleviate welfare problems

in the camp. He set up a camp "cabinet," which served as the POWs' administrative agency, and then organized

committees to address specific issues. The emphasis of this social relief program was on prisoners' aiding

their comrades through their period of confinement. Organized as the "Russian One Year's Volunteers," the POWs

adopted policies and implemented changes that improved living conditions in the camp. One committee focused on

expanding relief work in the hospitals, especially for the critically ill. They worked in conjunction with the

regimental physician to improve conditions, and Reitzel supported their work by providing supplies and equipment,

including musical instruments. Through this self-help program, prisoners avoided boredom and inactivity and

channeled their interests and energies in a positive direction. From Reitzel's perspective, this relief work

had particular rewards for the Association. Not only would Russian prisoners return home after the war with a

warm spot for the YMCA in their hearts, which would lay the basis for postwar Association expansion, but several

of these men indicated their interest in becoming YMCA secretaries after the war. By recruiting native secretaries,

the Association would gain a tremendous advantage in developing future organizations in Russia once the fighting

ended.23

27

The YMCA also began operations in Somorja, Boldagasszonyfa, Dunaszerdahly, Ostffyasszonyfa, and Nagymegyer

in Hungary in July 1916. Reitzel established and maintained YMCA POW operations at Ostffiassyzonyfa and

Somorja until March 1917. World's Alliance secretaries conducted the POW programs at the other three camps.

Schoop, a Swiss secretary, started the Association program at Boldogasszonyfa after an inspection trip to

the prison in May 1916.

The YMCA also began operations in Somorja, Boldagasszonyfa, Dunaszerdahly, Ostffyasszonyfa, and Nagymegyer

in Hungary in July 1916. Reitzel established and maintained YMCA POW operations at Ostffiassyzonyfa and

Somorja until March 1917. World's Alliance secretaries conducted the POW programs at the other three camps.

Schoop, a Swiss secretary, started the Association program at Boldogasszonyfa after an inspection trip to

the prison in May 1916.

This prison was filled with Serbian POWs who were in great need of attention. Schoop set up three YMCA

elementary schools to combat the rampant illiteracy. After acquiring a barrack, the secretary modified the

building for use with a motion picture theater, lecture hall, reading rooms, and library. He was able to

obtain a small library of one hundred books in Serbian, which became the nucleus of the POW library. Schoop also

acquired games for the reading rooms.

This prison was filled with Serbian POWs who were in great need of attention. Schoop set up three YMCA

elementary schools to combat the rampant illiteracy. After acquiring a barrack, the secretary modified the

building for use with a motion picture theater, lecture hall, reading rooms, and library. He was able to

obtain a small library of one hundred books in Serbian, which became the nucleus of the POW library. Schoop also

acquired games for the reading rooms.

In addition, Schoop divided the lecture room in half and encouraged the guards to use one of the spaces.

A soldier's library for the guards began when an officer donated forty Hungarian books to the Association.

Schoop maintained YMCA operations in Boldagasszonyfa until the end of the war. Heinrich A. Münger, also

a Swiss secretary, supervised Association operations in Dunaszerdahly and Nagymegyer, beginning in June 1916.

The first prison camp was composed primarily of Serbian prisoners, while the latter prison was filled with

Russian POWs. A few months after his initial work at these camps, Münger instituted YMCA services at Munger,

near Nagymegyer, a prison camp for Serbian POWs. Münger continued to serve at these three POW camps for the

duration of World War I.24

In addition, Schoop divided the lecture room in half and encouraged the guards to use one of the spaces.

A soldier's library for the guards began when an officer donated forty Hungarian books to the Association.

Schoop maintained YMCA operations in Boldagasszonyfa until the end of the war. Heinrich A. Münger, also

a Swiss secretary, supervised Association operations in Dunaszerdahly and Nagymegyer, beginning in June 1916.

The first prison camp was composed primarily of Serbian prisoners, while the latter prison was filled with

Russian POWs. A few months after his initial work at these camps, Münger instituted YMCA services at Munger,

near Nagymegyer, a prison camp for Serbian POWs. Münger continued to serve at these three POW camps for the

duration of World War I.24

28

Another major prison camp in Hungary that was home to an extensive Association operation was Kenyermezö,

one of the largest in the kingdom. Anthony W. Chez started working in the prison, which had a predominantly

Russian POW population, in September 1916. One of his first projects was to open a school constructed by the

prisoners. Within a month of the school's opening, Chez reported that it was filled to capacity. He also

provided entertainment with a kinetoscope, a performance many POWs had never before seen. He took the machine

to the camp hospital where four hundred men crowded in to see shows. Due to the success of these programs, Chez was

constantly searching for additional Russian books, especially lesson texts, and a phonograph to expand his

entertainment program. Like other secretaries, Chez sought to establish good relations with the camp guards

and officials and provide them with YMCA services. He obtained a stock of Hungarian books to loan to officers

and guards. He also expanded services into the military hospitals around Kenyermezö. Chez took the

kinetoscope and gave shows for invalids and convalescents, with five hundred showing up for the first presentation.

Because of the popularity of the shows, the chief surgeon requested that the machine remain in the hospital.

Chez conducted operations in Kenyermezö until he departed in April 1917.25

Another major prison camp in Hungary that was home to an extensive Association operation was Kenyermezö,

one of the largest in the kingdom. Anthony W. Chez started working in the prison, which had a predominantly

Russian POW population, in September 1916. One of his first projects was to open a school constructed by the

prisoners. Within a month of the school's opening, Chez reported that it was filled to capacity. He also

provided entertainment with a kinetoscope, a performance many POWs had never before seen. He took the machine

to the camp hospital where four hundred men crowded in to see shows. Due to the success of these programs, Chez was

constantly searching for additional Russian books, especially lesson texts, and a phonograph to expand his