Table of Contents

Chapter 15

The American YMCA and Allied Prisoner Relief in the Ottoman Empire

1

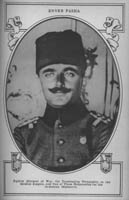

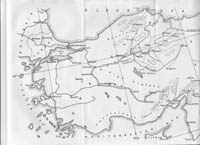

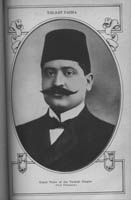

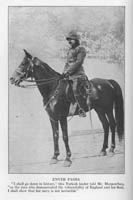

When war broke out in Europe in July 1914, the Ottoman Empire announced its neutrality. Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, proposed

a secret alliance with the Germans against the Russians, which the two powers signed in August. Although Turkey was to enter the

war when Russia attacked either Germany or Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans remained neutral for several months to gain time to complete

their mobilization preparations. During this period, the British government made several attempts to assure the continued neutrality

of Turkey, and the Russian regime sought to enter into an alliance with the Turks. The Ottomans, however, were firmly entrenched in

the Central Power camp, and in August, the Turks provided safe haven for two German warships, the SMS Goeben and SMS

Breslau, fleeing a British naval squadron.

When war broke out in Europe in July 1914, the Ottoman Empire announced its neutrality. Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, proposed

a secret alliance with the Germans against the Russians, which the two powers signed in August. Although Turkey was to enter the

war when Russia attacked either Germany or Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans remained neutral for several months to gain time to complete

their mobilization preparations. During this period, the British government made several attempts to assure the continued neutrality

of Turkey, and the Russian regime sought to enter into an alliance with the Turks. The Ottomans, however, were firmly entrenched in

the Central Power camp, and in August, the Turks provided safe haven for two German warships, the SMS Goeben and SMS

Breslau, fleeing a British naval squadron.

The Turkish government "purchased" these warships from the Germans to replace two battleships that were under construction in

Britain and had been commandeered by the English government. The German crews simply changed uniforms and manned the Turkish warships

in a military operation against southern Russian ports on the Black Sea. In late October, the Turks bombarded Odessa, Sebastopol,

and Theodosia, in response to which Russia declared war against the Ottoman Empire on 2 November 1914. The British also moved

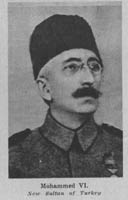

against the Ottomans, annexing Cyprus in November and proclaiming a protectorate over Egypt in December. As Caliph and leader of

the Muslim world, Sultan Mohammed V declared a jihad (holy war) on November 14 against all nations fighting Turkey or its

allies. The World War now encompassed most of the Near East.1

The Turkish government "purchased" these warships from the Germans to replace two battleships that were under construction in

Britain and had been commandeered by the English government. The German crews simply changed uniforms and manned the Turkish warships

in a military operation against southern Russian ports on the Black Sea. In late October, the Turks bombarded Odessa, Sebastopol,

and Theodosia, in response to which Russia declared war against the Ottoman Empire on 2 November 1914. The British also moved

against the Ottomans, annexing Cyprus in November and proclaiming a protectorate over Egypt in December. As Caliph and leader of

the Muslim world, Sultan Mohammed V declared a jihad (holy war) on November 14 against all nations fighting Turkey or its

allies. The World War now encompassed most of the Near East.1

2

In September 1914, Darius A. Davis reported to the International Committee that Turkish preparations for the war had begun to strain

Association operations. The government had mobilized the army, provisioned the fleet, suppressed the Capitulations, and closed the

Dardanelles. The YMCA in Turkey felt the effects of these actions, since many members had either enlisted in the army or fled the

country, and the loss of membership resulted in a financial drain on the organization. The Constantinople Association lost three members

of its Board of Managers due to the war, but the American secretaries continued their relief work.2

In September 1914, Darius A. Davis reported to the International Committee that Turkish preparations for the war had begun to strain

Association operations. The government had mobilized the army, provisioned the fleet, suppressed the Capitulations, and closed the

Dardanelles. The YMCA in Turkey felt the effects of these actions, since many members had either enlisted in the army or fled the

country, and the loss of membership resulted in a financial drain on the organization. The Constantinople Association lost three members

of its Board of Managers due to the war, but the American secretaries continued their relief work.2

3

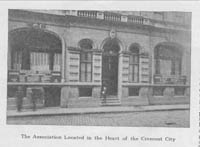

In Constantinople, Ernst O. Jacob and Dirk Johannes Van Bommel kept the Association running in temporary quarters while the

permanent building underwent renovations. This was difficult, since the Constantinople Association had lost over two hundred members due

to the mobilizations of the Turkish and Greek armies. Van Bommel added several more evening classes including Italian, bookkeeping,

and music. The members joined the Mandolin and Guitar Club and formed a Sporting Club to pursue outdoor sports. He also expanded

social work to counter vices, offering classes and discussion groups on subjects such as dishonesty. Jacob focused on writing,

editing, and managing the Association Quarterly, which took a great deal of his time. The highlight of the first year of the war

was the opening of the new Constantinople Association building in September 1915. The official inauguration was celebrated on

October 15, as U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau delivered the congratulatory address to an assembly of five hundred guests. The YMCA was

one of the few organizations, outside of the government, that was able to secure construction crews and material during wartime

to finish the remodeling. The facility did lack a gymnasium, but the Association planned to rectify that deficiency as soon as

the war was over.3

In Constantinople, Ernst O. Jacob and Dirk Johannes Van Bommel kept the Association running in temporary quarters while the

permanent building underwent renovations. This was difficult, since the Constantinople Association had lost over two hundred members due

to the mobilizations of the Turkish and Greek armies. Van Bommel added several more evening classes including Italian, bookkeeping,

and music. The members joined the Mandolin and Guitar Club and formed a Sporting Club to pursue outdoor sports. He also expanded

social work to counter vices, offering classes and discussion groups on subjects such as dishonesty. Jacob focused on writing,

editing, and managing the Association Quarterly, which took a great deal of his time. The highlight of the first year of the war

was the opening of the new Constantinople Association building in September 1915. The official inauguration was celebrated on

October 15, as U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau delivered the congratulatory address to an assembly of five hundred guests. The YMCA was

one of the few organizations, outside of the government, that was able to secure construction crews and material during wartime

to finish the remodeling. The facility did lack a gymnasium, but the Association planned to rectify that deficiency as soon as

the war was over.3

4

Student work also continued at full force throughout the Near East. Jacob reported that YMCA programs had expanded at several

points during 1915. Sunday schools and a boys' club began operations at Anatolia College. During a revival at St. Paul's College

in Tarsus, two-thirds of the student body decided to join the Student Association. A five-day Association conference was held at

the International College in Smyrna in July to discuss political and educational opportunities in the Near East after the war.

Most importantly, the students at the International College managed to maintain high moral standards, with the help of prayer

and evangelistic meetings led by the secretary, after an Allied naval bombardment forced the girl's school to close and integrate

with the men's college. Jacob believed that the Lebanon Conference had firmly established the Student Volunteer Movement as a

major moral force in the Ottoman Empire. At Robert College in Constantinople, Owen Pence increased the number of Bible classes

from two to eight, although the academic year was cut short when many of the students were drafted. In May 1915, Pence conducted

a YMCA conference that reviewed the Student Association's activities and planned for the next academic year. When the college

reopened in September, Pence reported that a new spirit permeated the college, and that students were free to develop new Association

methods and ideas. The Student Association was divided into a number of committees (meeting, poster, campus service, and benevolent)

to promote social welfare programs. Pence did note that operations were hindered by the fear of Protestant propaganda, and that

this suspicion spread insidiously across the campus.4 To maintain friendly

relations with the Ottomans, the American secretaries offered to provide relief work for Turkish soldiers, but they found it

very difficult to set up relief operations. The Ottoman government made every effort to give the Turkish Army a strong consciousness

of its Muslim character and mission, and military officials rejected any effort that would weaken this message. In January 1915,

the YMCA made small inroads regarding War Work when the secretaries decided to open the Association building on Fridays to troops

at the School of Reserve Officers. They conducted a Bible class for men who decided to participate, although their numbers remained

small.5

Student work also continued at full force throughout the Near East. Jacob reported that YMCA programs had expanded at several

points during 1915. Sunday schools and a boys' club began operations at Anatolia College. During a revival at St. Paul's College

in Tarsus, two-thirds of the student body decided to join the Student Association. A five-day Association conference was held at

the International College in Smyrna in July to discuss political and educational opportunities in the Near East after the war.

Most importantly, the students at the International College managed to maintain high moral standards, with the help of prayer

and evangelistic meetings led by the secretary, after an Allied naval bombardment forced the girl's school to close and integrate

with the men's college. Jacob believed that the Lebanon Conference had firmly established the Student Volunteer Movement as a

major moral force in the Ottoman Empire. At Robert College in Constantinople, Owen Pence increased the number of Bible classes

from two to eight, although the academic year was cut short when many of the students were drafted. In May 1915, Pence conducted

a YMCA conference that reviewed the Student Association's activities and planned for the next academic year. When the college

reopened in September, Pence reported that a new spirit permeated the college, and that students were free to develop new Association

methods and ideas. The Student Association was divided into a number of committees (meeting, poster, campus service, and benevolent)

to promote social welfare programs. Pence did note that operations were hindered by the fear of Protestant propaganda, and that

this suspicion spread insidiously across the campus.4 To maintain friendly

relations with the Ottomans, the American secretaries offered to provide relief work for Turkish soldiers, but they found it

very difficult to set up relief operations. The Ottoman government made every effort to give the Turkish Army a strong consciousness

of its Muslim character and mission, and military officials rejected any effort that would weaken this message. In January 1915,

the YMCA made small inroads regarding War Work when the secretaries decided to open the Association building on Fridays to troops

at the School of Reserve Officers. They conducted a Bible class for men who decided to participate, although their numbers remained

small.5

5 Association relief operations expanded as the war continued. In June 1915, Jacob began relief work at the Tash Kishle Barracks in Constantinople, the same facility Davis had worked at during the Balkan Wars. The Turks placed Jacob in charge of repairing and cleaning the 440-bed hospital for wounded and sick troops. Over a ten-day period, he supervised a crew of fifty men that included whitewashers, painters, and carpenters. The secretary hired twelve cleaning women to maintain sanitary conditions. Once the work was completed, Jacob accepted responsibility for keeping the American Red Cross section of the hospital clean, organized, and in good repair. While Jacob wanted greater responsibilities, two members of the Board of Managers, Dr. William W. Peet and Dr. M. Bowen, assured him that with his technical training and knowledge of Turkish, he could provide a service that would not be possible for most Americans. Hospital officials replaced Jacob in September 1915 with a Turkish superintendent, but the American secretary returned to work in January 1916 because the Turkish official had broken down under the heavy strain. Pence conducted similar work in another Turkish military hospital beginning in May 1915. He helped dress bandages for the wounded in the morning and organized Greek, Armenian, and Bulgarian students in rolling bandages. At the Association building, Jacob organized English Bible classes for Christian soldiers in the Turkish Army.6

6

Despite these services for the Turkish Army, the opportunities for the Association to conduct relief work gradually deteriorated.

In his annual report in September 1916, Jacob declared that "Turkey was miserable and work disheartening over the past year." In

January 1915, forty Associations thrived across the Ottoman Empire, but within a year only five remained in operation. The national

Association's work had ground almost to a halt by the beginning of 1916. Student Association work continued at Robert College and the

International College, but at a greatly reduced level. Pence found that Turkish suspicion of foreigners and Protestant propaganda

undermined his work at Robert College. By August 1916, he closed down operations at the school and eventually departed Constantinople

for assignment in France. The Pera Association no longer held meetings, socials, or athletic competitions, since military service

had taken away most of the members. The Greek Bible classes were canceled, leaving only the English Bible and moral/social problem

classes.

Despite these services for the Turkish Army, the opportunities for the Association to conduct relief work gradually deteriorated.

In his annual report in September 1916, Jacob declared that "Turkey was miserable and work disheartening over the past year." In

January 1915, forty Associations thrived across the Ottoman Empire, but within a year only five remained in operation. The national

Association's work had ground almost to a halt by the beginning of 1916. Student Association work continued at Robert College and the

International College, but at a greatly reduced level. Pence found that Turkish suspicion of foreigners and Protestant propaganda

undermined his work at Robert College. By August 1916, he closed down operations at the school and eventually departed Constantinople

for assignment in France. The Pera Association no longer held meetings, socials, or athletic competitions, since military service

had taken away most of the members. The Greek Bible classes were canceled, leaving only the English Bible and moral/social problem

classes.

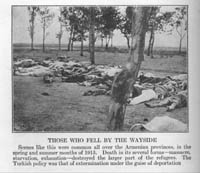

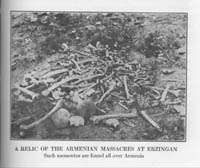

7 Even the Association Quarterly suspended publication in January, leaving Jacob with little to do. While the Orthodox ecclesiastics continued to support the YMCA in Constantinople, the Association worried about their Armenian supporters. By early 1916, it was clear that the Ottoman government was conducting a wholesale purge of its Christian nationals, with official efforts focusing on the Armenians. Jacob reported that the Turkish government believed that the:

…Christian races must be reduced to a state where they would be forever negligible in the development of a Turkey for Turks. They planned to completely annihilate the national life and institutions of the Armenian race… The Turkish program was fiendishly successful-hundreds of thousands of Armenians had died and many more would perish. The hopes of the Armenians were utterly crushed… As a race and as individuals they feel themselves doomed as long as the Turk is their lord.7

The YMCA had lost at least thirty Associations among the Armenians due to their forced deportation. Jacob heard that the Turks planned similar operations against the Syrian Christians, and he also feared for the Greek Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire if Greece joined the Allies in the war. It was becoming impossible for the American YMCA secretaries to continue their welfare program in Turkey.8

8

The staff of the U.S. embassy supported the American secretaries. Jacob praised Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Consul-General

G. Bie Ravndal, and the other members of the staff for firmly backing the YMCA in its dealings with the Ottoman government

(Ravndal was a member of the Association's Board of Managers). As relations with the Turkish government deteriorated, Morgenthau

advised the American YMCA in November 1915 to discontinue most activities in Constantinople. The city's chief of police proposed

that the government requisition the Association building to serve as the new police headquarters, but Morgenthau intervened and

prevented the police from seizing the facility.

The U.S. ambassador warned that the Turks would undoubtedly renew their attempts to seize YMCA property, and recommended that

the Association dissolve its Board of Managers and form a new directorship; the secretaries and board members agreed to this

proposal in December. A new board of directors, consisting of five Americans and three Germans (including Bowen, Peet, Ravndal,

and G. H. Huntington), replaced the old Board of Managers. When Morgenthau left Constantinople in 1916, he was replaced as

ambassador by Abram I. Elkus, who supported the American YMCA with as much enthusiasm as his predecessor. When the Turkish

government imposed a "club tax" of 15 percent of the rental value of the building on the YMCA (a tax assessed on clubs, casinos,

and beer halls), the Association paid, although Elkus attempted to intervene on the Red Triangle's behalf. He recommended that

the Board of Directors not resume their activities due to government opposition.9

G. Bie Ravndal, and the other members of the staff for firmly backing the YMCA in its dealings with the Ottoman government

(Ravndal was a member of the Association's Board of Managers). As relations with the Turkish government deteriorated, Morgenthau

advised the American YMCA in November 1915 to discontinue most activities in Constantinople. The city's chief of police proposed

that the government requisition the Association building to serve as the new police headquarters, but Morgenthau intervened and

prevented the police from seizing the facility.

The U.S. ambassador warned that the Turks would undoubtedly renew their attempts to seize YMCA property, and recommended that

the Association dissolve its Board of Managers and form a new directorship; the secretaries and board members agreed to this

proposal in December. A new board of directors, consisting of five Americans and three Germans (including Bowen, Peet, Ravndal,

and G. H. Huntington), replaced the old Board of Managers. When Morgenthau left Constantinople in 1916, he was replaced as

ambassador by Abram I. Elkus, who supported the American YMCA with as much enthusiasm as his predecessor. When the Turkish

government imposed a "club tax" of 15 percent of the rental value of the building on the YMCA (a tax assessed on clubs, casinos,

and beer halls), the Association paid, although Elkus attempted to intervene on the Red Triangle's behalf. He recommended that

the Board of Directors not resume their activities due to government opposition.9

9

Since Association work was effectively closed down as a result of the dissolution of the Board of Managers, tensions with the Turkish

government, and wartime mobilization, the YMCA had to decide what to do with the Constantinople property. At the final Board of

Managers meeting in December 1915, Ravndal had suggested that the YMCA suspend its operations and rent the building to the American

embassy, but the board members did not reach a decision. The new Board of Directors held a meeting in June 1916 to plan a course

of action. Jacob had already discussed renting the facility to the Danish embassy with Ambassador Morgenthau. Jacob thought the

building was large enough to rent to both the American and Danish embassies. The directorship voted to rent the property to either

the Danes or the ministry of some other neutral power. The International Committee also entered the equation at this point. The

American YMCA agreed to provide subsidies to maintain the building in Constantinople, but since the building was in minimal use,

these funds could be better spent on other wartime projects. The International Committee preferred that the Constantinople

Association lease the property for the cost of the maintenance of the building, with the proviso that the building be returned

ready for normal use at the end of the war. John R. Mott had a conference with Ambassador Elkus in August 1916 to discuss the

future of the property.10

Since Association work was effectively closed down as a result of the dissolution of the Board of Managers, tensions with the Turkish

government, and wartime mobilization, the YMCA had to decide what to do with the Constantinople property. At the final Board of

Managers meeting in December 1915, Ravndal had suggested that the YMCA suspend its operations and rent the building to the American

embassy, but the board members did not reach a decision. The new Board of Directors held a meeting in June 1916 to plan a course

of action. Jacob had already discussed renting the facility to the Danish embassy with Ambassador Morgenthau. Jacob thought the

building was large enough to rent to both the American and Danish embassies. The directorship voted to rent the property to either

the Danes or the ministry of some other neutral power. The International Committee also entered the equation at this point. The

American YMCA agreed to provide subsidies to maintain the building in Constantinople, but since the building was in minimal use,

these funds could be better spent on other wartime projects. The International Committee preferred that the Constantinople

Association lease the property for the cost of the maintenance of the building, with the proviso that the building be returned

ready for normal use at the end of the war. John R. Mott had a conference with Ambassador Elkus in August 1916 to discuss the

future of the property.10

10

In September 1916, the board met again but voted not to lease the building. But the International Committee intervened and

persuaded the directors to change their minds. Ravndal pointed out to the directorship that the American embassy needed additional

room to carry out POW work and other relief operations in the Ottoman Empire. When Turkey entered the war, the U.S. embassy

became responsible for protecting the interests in the Ottoman Empire of Britain, France, and Russia, plus four other belligerents.

As a result, the U.S. staff was pressed for space in the embassy and was searching for an annex, and Ravndal argued that the

Association building would be put to good use housing the relief operations of the embassy staff. As a result, the Board of

Directors voted to lease the building to the U.S. embassy for $4,200 per year. Van Bommel and his family would occupy the top

floor of the facility as caretakers and assist the embassy staff in its relief work. American officials took over the building

(which was directly adjacent to the U.S. embassy) on November 28. Because of the cutback in YMCA operations, Jacob decided in

June 1916 to return to the United States in preparation for POW work in Germany. Because of his knowledge of German and his

Association experience, the International Committee accepted his transfer to Conrad Hoffman's staff. This left Van

Bommel the last representative of the American YMCA in the Ottoman Empire.11

In September 1916, the board met again but voted not to lease the building. But the International Committee intervened and

persuaded the directors to change their minds. Ravndal pointed out to the directorship that the American embassy needed additional

room to carry out POW work and other relief operations in the Ottoman Empire. When Turkey entered the war, the U.S. embassy

became responsible for protecting the interests in the Ottoman Empire of Britain, France, and Russia, plus four other belligerents.

As a result, the U.S. staff was pressed for space in the embassy and was searching for an annex, and Ravndal argued that the

Association building would be put to good use housing the relief operations of the embassy staff. As a result, the Board of

Directors voted to lease the building to the U.S. embassy for $4,200 per year. Van Bommel and his family would occupy the top

floor of the facility as caretakers and assist the embassy staff in its relief work. American officials took over the building

(which was directly adjacent to the U.S. embassy) on November 28. Because of the cutback in YMCA operations, Jacob decided in

June 1916 to return to the United States in preparation for POW work in Germany. Because of his knowledge of German and his

Association experience, the International Committee accepted his transfer to Conrad Hoffman's staff. This left Van

Bommel the last representative of the American YMCA in the Ottoman Empire.11

The Y.M.C.A. and POW Relief in the Turkish Empire during World War I

11

While the lot of the Turkish soldier was very difficult in the Ottoman Army, the situation for prisoners-of-war was far worse.

The Turks did not have many opportunities to seize prisoners for the first two years of the war because their military operations

While the lot of the Turkish soldier was very difficult in the Ottoman Army, the situation for prisoners-of-war was far worse.

The Turks did not have many opportunities to seize prisoners for the first two years of the war because their military operations

were limited to a weak strike against the Suez Canal in February 1915 and defensive

operations in Gallipoli from April 1915 to

January 1916. While fighting for control of the Straits was intense (the Allies sent approximately five hundred thousand men into the campaign,

and over half became battle casualties; Turkish losses were equally high), the Allies never broke out of their beachheads, and

the Turks allowed the Allied forces to evacuate without attacking. As a result, the Turks captured relatively few prisoners. The

Ottomans would not achieve a major military success until April of 1916, at Kut-al-Amara.

were limited to a weak strike against the Suez Canal in February 1915 and defensive

operations in Gallipoli from April 1915 to

January 1916. While fighting for control of the Straits was intense (the Allies sent approximately five hundred thousand men into the campaign,

and over half became battle casualties; Turkish losses were equally high), the Allies never broke out of their beachheads, and

the Turks allowed the Allied forces to evacuate without attacking. As a result, the Turks captured relatively few prisoners. The

Ottomans would not achieve a major military success until April of 1916, at Kut-al-Amara.

12

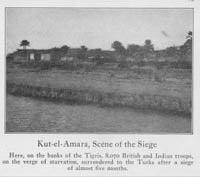

The British landed forces at Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf in November 1914 in preparation for an assault along the Tigris

and Euphrates Rivers against Baghdad. In June 1915, General Charles Townshend led an expeditionary force of British and Indian

troops from Kuwait for the advance through Mesopotamia. The Anglo-Indian force made phenomenal progress until the Turks stopped

the Allied advance at the bloody battle of Ctesiphon, fifteen miles southeast of Baghdad, in November 1915.

Townshend withdrew to the fortress garrison at Kut-al-Amara on the Tigris River so

The British landed forces at Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf in November 1914 in preparation for an assault along the Tigris

and Euphrates Rivers against Baghdad. In June 1915, General Charles Townshend led an expeditionary force of British and Indian

troops from Kuwait for the advance through Mesopotamia. The Anglo-Indian force made phenomenal progress until the Turks stopped

the Allied advance at the bloody battle of Ctesiphon, fifteen miles southeast of Baghdad, in November 1915.

Townshend withdrew to the fortress garrison at Kut-al-Amara on the Tigris River so

that his disease- and heat-ridden troops could

recuperate. Over ten thousand British and Indian troops, 3,500 Indian non-combatants, and three thousand sick and wounded arrived in Kut. The

Turks rushed forces to Kut and encircled the garrison. The siege began on December 4, and the Allied garrison held out, fighting

against malaria and starvation, waiting for the arrival of a British relief column. The siege lasted 147 days before Townshend

surrendered on 29 April 1916.12

that his disease- and heat-ridden troops could

recuperate. Over ten thousand British and Indian troops, 3,500 Indian non-combatants, and three thousand sick and wounded arrived in Kut. The

Turks rushed forces to Kut and encircled the garrison. The siege began on December 4, and the Allied garrison held out, fighting

against malaria and starvation, waiting for the arrival of a British relief column. The siege lasted 147 days before Townshend

surrendered on 29 April 1916.12

13

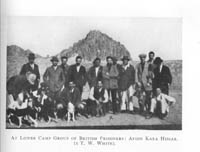

On 6 May 1916, the Turks began a 1,200-mile forced march of the British prisoners across the Syrian Desert from Kut. Mounted

Arab and Kurdish guards prodded over 2,500 British soldiers with rifle butts and whips on the long death march. Starvation,

thirst, disease, and exhaustion thinned out the British column, and only 837 soldiers survived the march. Turkish treatment of the

On 6 May 1916, the Turks began a 1,200-mile forced march of the British prisoners across the Syrian Desert from Kut. Mounted

Arab and Kurdish guards prodded over 2,500 British soldiers with rifle butts and whips on the long death march. Starvation,

thirst, disease, and exhaustion thinned out the British column, and only 837 soldiers survived the march. Turkish treatment of the

Indian troops was better, as the Ottomans attempted to attract fellow Muslims to their cause. During the siege, the Turks attempted

to inspire mutiny among the Indian forces in Kut by leaving bundles of propaganda pamphlets along the barbed-wire front lines

calling on the Indians to murder their British officers and join the Sultan's forces. While the British attempted to intercept

Indian troops was better, as the Ottomans attempted to attract fellow Muslims to their cause. During the siege, the Turks attempted

to inspire mutiny among the Indian forces in Kut by leaving bundles of propaganda pamphlets along the barbed-wire front lines

calling on the Indians to murder their British officers and join the Sultan's forces. While the British attempted to intercept

these pamphlets, some did get through and led to a number of desertions.

But when the garrison fell, 9,300 Indian troops and non-combatants joined the death march. For the Turks, the success at Kut was a

tremendous moral victory. They had demonstrated that the all-powerful and all-conquering British Raj was a myth. While the British

these pamphlets, some did get through and led to a number of desertions.

But when the garrison fell, 9,300 Indian troops and non-combatants joined the death march. For the Turks, the success at Kut was a

tremendous moral victory. They had demonstrated that the all-powerful and all-conquering British Raj was a myth. While the British

government offered the Turks £ 2 million in gold in exchange for the repatriation of the garrison, the Ottomans turned down the

offer. Instead, they used the POWs as propaganda tools. The Turks paraded the British prisoners through the streets of Baghdad

and other towns in the empire, where the Ottoman subjects could revile, stone, and spit on the hated English. This public taunting

of the proud British imperialists carried an important message: the British could be humbled, degraded, and enslaved. The defeat

at Kut marked an important step towards the collapse of the British Empire.13

government offered the Turks £ 2 million in gold in exchange for the repatriation of the garrison, the Ottomans turned down the

offer. Instead, they used the POWs as propaganda tools. The Turks paraded the British prisoners through the streets of Baghdad

and other towns in the empire, where the Ottoman subjects could revile, stone, and spit on the hated English. This public taunting

of the proud British imperialists carried an important message: the British could be humbled, degraded, and enslaved. The defeat

at Kut marked an important step towards the collapse of the British Empire.13

14

In general, the Turks did not follow Western rules and regulations in dealing with war prisoners. The Western press described in

detail the atrocities faced by Allied (especially British) POWs. Captured soldiers were herded like sheep by mounted Arab troopers,

who freely used sticks and whips to keep stragglers marching. Food was very scarce, and the POWs rarely had access to fresh water.

The desert climate where most of the campaigning took place had a debilitating impact on prisoners, especially the heat and dust.

Often Turkish troops and guards relieved captives of their water bottles, boots, and uniforms, leaving the POWs in an assortment of

rags-Ottoman officers exercised very little control over their men.

When prisoners collapsed exhausted, starved, or ill, many were left to fend for themselves in hovels. These mud-walled "shelters"

were often filled with vermin, and soldiers had to resort to begging from passing Arabs for scraps of food. Many of these invalids

were robbed, stripped of their last clothing, and left to die. After marching across the desert, the remaining POWs entered prison

camps where they received insufficient food and faced epidemics of dysentery, cholera, and malaria. Many prisoners were simply

incarcerated in regular jails with common criminals, without regard for rank or status. Prisoners sat in bare cells filled with

vermin, few washing facilities, and no physical exercise. The POW under Turkish care faced a cruel existence.14

In general, the Turks did not follow Western rules and regulations in dealing with war prisoners. The Western press described in

detail the atrocities faced by Allied (especially British) POWs. Captured soldiers were herded like sheep by mounted Arab troopers,

who freely used sticks and whips to keep stragglers marching. Food was very scarce, and the POWs rarely had access to fresh water.

The desert climate where most of the campaigning took place had a debilitating impact on prisoners, especially the heat and dust.

Often Turkish troops and guards relieved captives of their water bottles, boots, and uniforms, leaving the POWs in an assortment of

rags-Ottoman officers exercised very little control over their men.

When prisoners collapsed exhausted, starved, or ill, many were left to fend for themselves in hovels. These mud-walled "shelters"

were often filled with vermin, and soldiers had to resort to begging from passing Arabs for scraps of food. Many of these invalids

were robbed, stripped of their last clothing, and left to die. After marching across the desert, the remaining POWs entered prison

camps where they received insufficient food and faced epidemics of dysentery, cholera, and malaria. Many prisoners were simply

incarcerated in regular jails with common criminals, without regard for rank or status. Prisoners sat in bare cells filled with

vermin, few washing facilities, and no physical exercise. The POW under Turkish care faced a cruel existence.14

15

The plight of Allied POWs in Turkish hands concerned the American secretaries in Constantinople. In December 1915, Mott instructed

Jacob to approach Turkish officials about the American YMCA setting up a War Prisoners' Aid (WPA) program in the Ottoman Empire.

Jacob immediately took up the subject with Bowen, Peet, and Van Bommel. Although all of the Association officials were pessimistic

about being granted access to Turkish POWs, they agreed that their best strategy was negotiation through the U.S. embassy. Ambassador

Morgenthau was very interested in the proposal, but he was overwhelmed with preparations for his departure. He turned the matter over

to Mr. Philip, the embassy's Charge d'Affaires. As the American official responsible for the care of Allied POWs in the Ottoman Empire

since the beginning of the war, Philip embraced the YMCA's offer. He endorsed the WPA plan without qualification and was optimistic

about its implementation. Philip took up the proposal with Halil Bey, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and presented his case to the

ministry staff. In the meantime, Jacob attempted to get other influential Turks interested in the plan. Through Graf Luttichau, a

member of the Constantinople Association's Board of Managers, Jacob received an introduction at the German embassy. After an interview,

the German ambassador promised to speak in favor of the YMCA proposal with Halil Bey. When Philip met with Halil Bey several days

later, the Turkish minister reported that the German ambassador had explained the details of the WPA plan and that the German

government was grateful for what the American YMCA had done for German POWs in Britain and France. The German government supported

the implementation of a WPA program for Allied POWs in Turkey. The Foreign Minister stated that the Association proposal had made

a strong and favorable impression on the Turkish government.15

The plight of Allied POWs in Turkish hands concerned the American secretaries in Constantinople. In December 1915, Mott instructed

Jacob to approach Turkish officials about the American YMCA setting up a War Prisoners' Aid (WPA) program in the Ottoman Empire.

Jacob immediately took up the subject with Bowen, Peet, and Van Bommel. Although all of the Association officials were pessimistic

about being granted access to Turkish POWs, they agreed that their best strategy was negotiation through the U.S. embassy. Ambassador

Morgenthau was very interested in the proposal, but he was overwhelmed with preparations for his departure. He turned the matter over

to Mr. Philip, the embassy's Charge d'Affaires. As the American official responsible for the care of Allied POWs in the Ottoman Empire

since the beginning of the war, Philip embraced the YMCA's offer. He endorsed the WPA plan without qualification and was optimistic

about its implementation. Philip took up the proposal with Halil Bey, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and presented his case to the

ministry staff. In the meantime, Jacob attempted to get other influential Turks interested in the plan. Through Graf Luttichau, a

member of the Constantinople Association's Board of Managers, Jacob received an introduction at the German embassy. After an interview,

the German ambassador promised to speak in favor of the YMCA proposal with Halil Bey. When Philip met with Halil Bey several days

later, the Turkish minister reported that the German ambassador had explained the details of the WPA plan and that the German

government was grateful for what the American YMCA had done for German POWs in Britain and France. The German government supported

the implementation of a WPA program for Allied POWs in Turkey. The Foreign Minister stated that the Association proposal had made

a strong and favorable impression on the Turkish government.15

16

When the YMCA proposal was referred to Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, the final decision was delayed by his trips into

the interior. This gave Jacob time to get other influential people interested in the WPA plan. He approached men known to

hold the ear of the Minister of War, including Dr. Bessim Omer Pasha, the Vice President of the Turkish Red Crescent Society,

the channel through which foreign assistance was conveyed to Allied POWs. Jacob found the Red Crescent official reasonable and

amenable to the Association's proposal. After hearing the plan, he assured Jacob that he would urge its acceptance by both

the Minister of War and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Jacob also approached Captain Humann, the German naval attaché

and a personal friend of Enver Pasha. This lead was not pursued, however, after the U.S. embassy received word from the Ministry

of War that the WPA plan had been categorically refused.16

When the YMCA proposal was referred to Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, the final decision was delayed by his trips into

the interior. This gave Jacob time to get other influential people interested in the WPA plan. He approached men known to

hold the ear of the Minister of War, including Dr. Bessim Omer Pasha, the Vice President of the Turkish Red Crescent Society,

the channel through which foreign assistance was conveyed to Allied POWs. Jacob found the Red Crescent official reasonable and

amenable to the Association's proposal. After hearing the plan, he assured Jacob that he would urge its acceptance by both

the Minister of War and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Jacob also approached Captain Humann, the German naval attaché

and a personal friend of Enver Pasha. This lead was not pursued, however, after the U.S. embassy received word from the Ministry

of War that the WPA plan had been categorically refused.16

17

Although the Turkish government rejected the WPA plan, the Association secretaries were not ready to give up the project. Philip

promised to reopen negotiations personally with Enver Pasha, but, due to suspicion within the Ottoman government regarding

foreigners, it would take time. The Turks were even mistrustful of foreign representatives visiting prison camps. Philip had

repeatedly requested that the government send American representatives to the major prison compounds, but the Ottomans had

Although the Turkish government rejected the WPA plan, the Association secretaries were not ready to give up the project. Philip

promised to reopen negotiations personally with Enver Pasha, but, due to suspicion within the Ottoman government regarding

foreigners, it would take time. The Turks were even mistrustful of foreign representatives visiting prison camps. Philip had

repeatedly requested that the government send American representatives to the major prison compounds, but the Ottomans had

categorically denied them entry. One factor that might change Turkish POW policy was their recent victory in Mesopotamia.

Before April 1916, the Ottomans held very few Allied POWs, until the Turks won their victory at Kut-el-Amara. While a number

of these POWs remained in Baghdad for three months, the U.S. Consul, Mr. Brissell, worked to improve the prisoners' meager

rations. In August, the survivors marched to Asia Minor for final internment, either in prison camps or in labor detachments

(the Turks assigned many of the POWs to work on the Anatolia segment of the Berlin-to-Baghdad railroad). In November 1918, an official British report declared

that 3,290 British and Indian POWs from Kut-el-Amara had died in Turkish captivity, and an additional 2,222 were missing and

presumed dead.17

categorically denied them entry. One factor that might change Turkish POW policy was their recent victory in Mesopotamia.

Before April 1916, the Ottomans held very few Allied POWs, until the Turks won their victory at Kut-el-Amara. While a number

of these POWs remained in Baghdad for three months, the U.S. Consul, Mr. Brissell, worked to improve the prisoners' meager

rations. In August, the survivors marched to Asia Minor for final internment, either in prison camps or in labor detachments

(the Turks assigned many of the POWs to work on the Anatolia segment of the Berlin-to-Baghdad railroad). In November 1918, an official British report declared

that 3,290 British and Indian POWs from Kut-el-Amara had died in Turkish captivity, and an additional 2,222 were missing and

presumed dead.17

18

While the American secretaries had encountered a dead end in Constantinople, a new opportunity arose through the Austrian

Red Cross. Baron Markus von Spiegelfeld, a member of the War Prisoners' Aid committee in Austria-Hungary and an official in the

Austrian Red Cross, wrote to the President of the Turkish Red Crescent Society. Von Spiegelfeld introduced Christian Phildius,

General Secretary of the World's Alliance, who was traveling to Constantinople to organize World Committee activities in the

Ottoman Empire. He outlined WPA activities underway in the Dual Monarchy, and described the significant benefit they created

for Allied POWs in Austria-Hungary.

He pointed out that the American YMCA had already established extensive POW relief programs that were of great benefit to

Turkish prisoners in Russia. Von Spiegelfeld hoped that the Ottomans would take advantage of this philanthropic opportunity

to provide relief for Allied POWs in Turkey. This introduction gave the World's Alliance a foot in the door of the Ottoman

Empire. In addition, Frederic Penfield, U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, wrote an official letter of introduction for

Phildius to present to Ambassador Elkus in Constantinople. The Wilson Administration fully supported the Association's POW

work in Turkey. This correspondence was a very slow, but potentially promising start for YMCA WPA operations in the Near

East.18

While the American secretaries had encountered a dead end in Constantinople, a new opportunity arose through the Austrian

Red Cross. Baron Markus von Spiegelfeld, a member of the War Prisoners' Aid committee in Austria-Hungary and an official in the

Austrian Red Cross, wrote to the President of the Turkish Red Crescent Society. Von Spiegelfeld introduced Christian Phildius,

General Secretary of the World's Alliance, who was traveling to Constantinople to organize World Committee activities in the

Ottoman Empire. He outlined WPA activities underway in the Dual Monarchy, and described the significant benefit they created

for Allied POWs in Austria-Hungary.

He pointed out that the American YMCA had already established extensive POW relief programs that were of great benefit to

Turkish prisoners in Russia. Von Spiegelfeld hoped that the Ottomans would take advantage of this philanthropic opportunity

to provide relief for Allied POWs in Turkey. This introduction gave the World's Alliance a foot in the door of the Ottoman

Empire. In addition, Frederic Penfield, U.S. Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, wrote an official letter of introduction for

Phildius to present to Ambassador Elkus in Constantinople. The Wilson Administration fully supported the Association's POW

work in Turkey. This correspondence was a very slow, but potentially promising start for YMCA WPA operations in the Near

East.18

19

The Constantinople Association's decision to shut down operations and rent the building to the U.S. embassy also opened a back

door to YMCA POW operations in Turkey. After occupying the Association building in November 1916, the embassy staff used the

facility for POW relief work, distributing various necessities from their home governments to prisoners of war. This relief

work was now centralized in the Association building. The ground floor served as offices and a waiting room. Additional

offices, a packing room, and an inspection room were set up on the second floor. The third floor became a storeroom for

overcoats, suits, underwear, boots, towels, soap, brushes, medicine, cocoa, tea, and other articles destined for POWs. The

embassy staff labeled, packed, and shipped these goods to war prisoners scattered across Asia Minor. Van Bommel participated

in this relief work in conjunction with American embassy personnel.19

The Constantinople Association's decision to shut down operations and rent the building to the U.S. embassy also opened a back

door to YMCA POW operations in Turkey. After occupying the Association building in November 1916, the embassy staff used the

facility for POW relief work, distributing various necessities from their home governments to prisoners of war. This relief

work was now centralized in the Association building. The ground floor served as offices and a waiting room. Additional

offices, a packing room, and an inspection room were set up on the second floor. The third floor became a storeroom for

overcoats, suits, underwear, boots, towels, soap, brushes, medicine, cocoa, tea, and other articles destined for POWs. The

embassy staff labeled, packed, and shipped these goods to war prisoners scattered across Asia Minor. Van Bommel participated

in this relief work in conjunction with American embassy personnel.19

20

After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Wilson Administration severed diplomatic relations with the

Ottoman Empire. As a result, the Netherlands legation took over the diplomatic interests of Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia,

formerly cared for by the American government, including taking over the lease and operations of the Constantinople Association.

Van Bommel, a Dutch national, was assigned to the Netherlands Consulate. The Dutch ambassador appointed Van Bommel as an

attaché to supervise the POW relief operations. The secretary had been working for the American embassy since December

1916, while receiving his YMCA salary from the International Committee. The Dutch government asked if the American Association

could continue to pay his wages, especially since Van Bommel's work was similar to the duties performed by WPA secretaries in Europe. The

International Committee accepted this arrangement. The one drawback to Van Bommel's position was that he could not visit POWs

in the field, but would have to remain in Constantinople.20

After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Wilson Administration severed diplomatic relations with the

Ottoman Empire. As a result, the Netherlands legation took over the diplomatic interests of Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia,

formerly cared for by the American government, including taking over the lease and operations of the Constantinople Association.

Van Bommel, a Dutch national, was assigned to the Netherlands Consulate. The Dutch ambassador appointed Van Bommel as an

attaché to supervise the POW relief operations. The secretary had been working for the American embassy since December

1916, while receiving his YMCA salary from the International Committee. The Dutch government asked if the American Association

could continue to pay his wages, especially since Van Bommel's work was similar to the duties performed by WPA secretaries in Europe. The

International Committee accepted this arrangement. The one drawback to Van Bommel's position was that he could not visit POWs

in the field, but would have to remain in Constantinople.20

21

As the Dutch POW attaché, Van Bommel now worked night and day for British, French, and Russian prisoners held in

the Ottoman Empire. He was in daily touch with members of the Ottoman government, including Enver Pasha and Mehmed Talaat Pasha,

the Grand Vizier. Van Bommel supervised twenty-five workers to provide supplies for roughly fifteen thousand Allied prisoners. POW relief

work included correspondence with prisoners and their governments (regarding the location and condition of the POWs), maintaining an information bureau, and

buying and distributing supplies and money (clothing, boots, comforts, and other goods) to POWs in various camps. As attaché,

Van Bommel hoped to improve the living conditions and treatment of Allied prisoners in Turkey.21

As the Dutch POW attaché, Van Bommel now worked night and day for British, French, and Russian prisoners held in

the Ottoman Empire. He was in daily touch with members of the Ottoman government, including Enver Pasha and Mehmed Talaat Pasha,

the Grand Vizier. Van Bommel supervised twenty-five workers to provide supplies for roughly fifteen thousand Allied prisoners. POW relief

work included correspondence with prisoners and their governments (regarding the location and condition of the POWs), maintaining an information bureau, and

buying and distributing supplies and money (clothing, boots, comforts, and other goods) to POWs in various camps. As attaché,

Van Bommel hoped to improve the living conditions and treatment of Allied prisoners in Turkey.21

22

The terrible conditions facing British POWs in the Ottoman Empire became a major issue in England. The Prisoners in Turkey

Committee was formed to improve the communication with and relief distribution to British POWs under Ottoman control. Members argued that

while the Turks might be more humane than the Germans, the conditions prisoners faced were far worse. They estimated that

almost half of the British and Indian POWs held by the Turks had died by the summer of 1918, and that their living standards

had to be improved.22

The terrible conditions facing British POWs in the Ottoman Empire became a major issue in England. The Prisoners in Turkey

Committee was formed to improve the communication with and relief distribution to British POWs under Ottoman control. Members argued that

while the Turks might be more humane than the Germans, the conditions prisoners faced were far worse. They estimated that

almost half of the British and Indian POWs held by the Turks had died by the summer of 1918, and that their living standards

had to be improved.22

23

The British and Turkish governments began negotiations in Switzerland in 1917 on improving conditions for POWs. The resulting

Bern Agreement was signed in December 1917, but the Turks did not ratify the document until April 1918. This document addressed

many vital issues. The first part dealt with the repatriation of wounded POWs. Under the treaty, three hundred British and seven hundred Indian

invalid prisoners were to be immediately exchanged for 1,500 Turkish invalids. In addition, future POWs with specific disabilities

would be immediately repatriated. The repatriations were to be conducted at sea on an exchange ship that sailed from Alexandria

bound for Scala Nuova, near Smyrna, which would also carry food and clothing for Allied POWs in Turkish prisons. By September

1918, the process of repatriation had not yet begun. The British government demanded that the German and Austro-Hungarian

governments guarantee the safety of this relief ship from submarines. The English attempted to work through the Anglo-German

Conference underway at The Hague, as well as through the Spanish ambassador in Vienna, the Swedish minister in London, and the Dutch

minister in Constantinople, all without results. Even if the Central Power governments extended the guarantee, it would take

ten weeks to inform U-boats at sea of the order.23

The British and Turkish governments began negotiations in Switzerland in 1917 on improving conditions for POWs. The resulting

Bern Agreement was signed in December 1917, but the Turks did not ratify the document until April 1918. This document addressed

many vital issues. The first part dealt with the repatriation of wounded POWs. Under the treaty, three hundred British and seven hundred Indian

invalid prisoners were to be immediately exchanged for 1,500 Turkish invalids. In addition, future POWs with specific disabilities

would be immediately repatriated. The repatriations were to be conducted at sea on an exchange ship that sailed from Alexandria

bound for Scala Nuova, near Smyrna, which would also carry food and clothing for Allied POWs in Turkish prisons. By September

1918, the process of repatriation had not yet begun. The British government demanded that the German and Austro-Hungarian

governments guarantee the safety of this relief ship from submarines. The English attempted to work through the Anglo-German

Conference underway at The Hague, as well as through the Spanish ambassador in Vienna, the Swedish minister in London, and the Dutch

minister in Constantinople, all without results. Even if the Central Power governments extended the guarantee, it would take

ten weeks to inform U-boats at sea of the order.23

24

The second part of the Anglo-Turkish treaty discussed the treatment of POWs held by both powers. This section included physical

concerns such as lodging, sanitation, supplies, and physical activities, and also issues of paramount importance to the YMCA

and its WPA activities. The treaty guaranteed each nation the right to prison camp visits, and to organize and promote self-help

committees. The treaty also made accommodations for religious services and improved communication with and information about

POWs.24

The second part of the Anglo-Turkish treaty discussed the treatment of POWs held by both powers. This section included physical

concerns such as lodging, sanitation, supplies, and physical activities, and also issues of paramount importance to the YMCA

and its WPA activities. The treaty guaranteed each nation the right to prison camp visits, and to organize and promote self-help

committees. The treaty also made accommodations for religious services and improved communication with and information about

POWs.24

25

While the spiritual and mental comfort of prisoners was important, the British government emphasized the physical needs of

POWs in Turkey during 1918. A report by a member of the House of Commons in July 1918 declared that 530 British and 733 Indian

POWs had died in Turkey since 1 January 1917. The British government had proven ineffective in sending food and clothing to

their imprisoned soldiers. Limited transportation meant supplies took many months (sometimes a year) to arrive, if they survived

the journey at all. To circumvent the transportation problem, the government forwarded money to POWs to purchase their own

While the spiritual and mental comfort of prisoners was important, the British government emphasized the physical needs of

POWs in Turkey during 1918. A report by a member of the House of Commons in July 1918 declared that 530 British and 733 Indian

POWs had died in Turkey since 1 January 1917. The British government had proven ineffective in sending food and clothing to

their imprisoned soldiers. Limited transportation meant supplies took many months (sometimes a year) to arrive, if they survived

the journey at all. To circumvent the transportation problem, the government forwarded money to POWs to purchase their own

provisions, but inflation in Turkey severely depreciated paper currency and made it difficult for POWs to purchase bread, sugar,

or potatoes. Prisoners also could not afford coal during the cold winter months in the mountains of Anatolia. Because conditions

were so bad, the Prisoners in Turkey Committee recommended that all British and Indian prisoners held by the Ottomans for eighteen

months or longer be exchanged immediately. The major drawback to this plan, however, was the lack of repatriation points. While

some prisoners were exchanged between the lines in Mesopotamia in 1916, a similar exchange would have been difficult in Palestine

in 1918 due to the fluid situation on this front. Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland were potential exchange points that

had yet to be explored.25

provisions, but inflation in Turkey severely depreciated paper currency and made it difficult for POWs to purchase bread, sugar,

or potatoes. Prisoners also could not afford coal during the cold winter months in the mountains of Anatolia. Because conditions

were so bad, the Prisoners in Turkey Committee recommended that all British and Indian prisoners held by the Ottomans for eighteen

months or longer be exchanged immediately. The major drawback to this plan, however, was the lack of repatriation points. While

some prisoners were exchanged between the lines in Mesopotamia in 1916, a similar exchange would have been difficult in Palestine

in 1918 due to the fluid situation on this front. Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland were potential exchange points that

had yet to be explored.25

26

The British government had attempted to augment inadequate food and clothing supplies in two other ways. First, the English

attempted to purchase goods in Constantinople and Aleppo, with limited success. Then the British government decided to send

food and clothing parcels via Switzerland through either the American Express Company or the international postal system.

While this system succeeded in getting goods directly to British POWs, only ten pounds of food per prisoner-and no

clothing-was transported to the Ottoman Empire between February and September 1918. During that same period, English POWs

in Germany each received six hundred pounds of food and two outfits of clothing.

Despite initial objections from the War Office, which was concerned with delivery guarantees, the House of Commons voted

in August 1918 to increase food and clothing shipments to British POWs in Turkey. The War Office authorized relatives to

send one hundred pounds of food monthly, clothing, and one blanket to British officers. Care committees could send sixty

pounds of food monthly, winter clothing (including a greatcoat), and a blanket to POWs of other ranks. In addition, the

War Office agreed to send a reserve of clothing and blankets (equal to one-quarter of the quantity dispatched in individual

parcels by relatives and care committees) to the Dutch minister in Constantinople. Food supplies for four months for officers

and men, along with clothing for the ranks, would also be shipped from Alexandria.26

The British government had attempted to augment inadequate food and clothing supplies in two other ways. First, the English

attempted to purchase goods in Constantinople and Aleppo, with limited success. Then the British government decided to send

food and clothing parcels via Switzerland through either the American Express Company or the international postal system.

While this system succeeded in getting goods directly to British POWs, only ten pounds of food per prisoner-and no

clothing-was transported to the Ottoman Empire between February and September 1918. During that same period, English POWs

in Germany each received six hundred pounds of food and two outfits of clothing.

Despite initial objections from the War Office, which was concerned with delivery guarantees, the House of Commons voted

in August 1918 to increase food and clothing shipments to British POWs in Turkey. The War Office authorized relatives to

send one hundred pounds of food monthly, clothing, and one blanket to British officers. Care committees could send sixty

pounds of food monthly, winter clothing (including a greatcoat), and a blanket to POWs of other ranks. In addition, the

War Office agreed to send a reserve of clothing and blankets (equal to one-quarter of the quantity dispatched in individual

parcels by relatives and care committees) to the Dutch minister in Constantinople. Food supplies for four months for officers

and men, along with clothing for the ranks, would also be shipped from Alexandria.26

27

Allied pressure on the Turkish government regarding POW conditions made the Ottomans reconsider their policies. During a trip

to Germany in September 1917, Christian Phildius learned of Turkish interest in having the World's Alliance discuss the POW

situation and establish a WPA program. In January 1918, Phildius finally gained access to Turkish officials and opened the

doors of Ottoman prisons to YMCA secretaries. By the beginning of the year, Phildius had letters of recommendation from the

International Red Cross Committee in Geneva and the presidents of the Austrian Red Cross Society, the Hungarian Red Cross Society, the Bulgarian

Red Cross Society, and the Turkish Red Crescent Society for presentation to

the Turkish government. He also carried personal introductions to Enver Pasha from General Friedrich of the Prisoners of War

Department of the German War Office, and from Graf Botho von Wedel, the German ambassador in Vienna. To further support his

credentials, Phildius obtained an official letter of appreciation from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War regarding WPA

services in the Dual Monarchy for presentation to the Turkish Ministry of War.27

Allied pressure on the Turkish government regarding POW conditions made the Ottomans reconsider their policies. During a trip

to Germany in September 1917, Christian Phildius learned of Turkish interest in having the World's Alliance discuss the POW

situation and establish a WPA program. In January 1918, Phildius finally gained access to Turkish officials and opened the

doors of Ottoman prisons to YMCA secretaries. By the beginning of the year, Phildius had letters of recommendation from the

International Red Cross Committee in Geneva and the presidents of the Austrian Red Cross Society, the Hungarian Red Cross Society, the Bulgarian

Red Cross Society, and the Turkish Red Crescent Society for presentation to

the Turkish government. He also carried personal introductions to Enver Pasha from General Friedrich of the Prisoners of War

Department of the German War Office, and from Graf Botho von Wedel, the German ambassador in Vienna. To further support his

credentials, Phildius obtained an official letter of appreciation from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War regarding WPA

services in the Dual Monarchy for presentation to the Turkish Ministry of War.27

28

After Phildius arrived in Constantinople on January 21, he visited Graf Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff, the former German Ambassador to the United States and the new ambassador

to the Ottoman Empire. Von Bernstorff immediately called the German Military Plenipotentiary, General de Lessow, and asked

him to employ his influence with the Turkish Ministry of War. De Lessow arranged an interview for Phildius with Enver Pasha,

provided his personal car for the appointment, and personally introduced him to the Minister of War. Hearing Phildius' proposal

for World's Alliance secretaries to begin WPA work in Turkish prisons, Enver Pasha agreed in principle to accepting Association

services. The Minister of War instructed the State Secretary, Mahmoud Kiamil Pasha, to talk with Phildius to develop a

specific plan. The Turkish secretary scheduled a meeting the next day at the War Office between Phildius and two representatives

of the Ministry of War and two delegates from the Red Crescent Society.28

After Phildius arrived in Constantinople on January 21, he visited Graf Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff, the former German Ambassador to the United States and the new ambassador

to the Ottoman Empire. Von Bernstorff immediately called the German Military Plenipotentiary, General de Lessow, and asked

him to employ his influence with the Turkish Ministry of War. De Lessow arranged an interview for Phildius with Enver Pasha,

provided his personal car for the appointment, and personally introduced him to the Minister of War. Hearing Phildius' proposal

for World's Alliance secretaries to begin WPA work in Turkish prisons, Enver Pasha agreed in principle to accepting Association

services. The Minister of War instructed the State Secretary, Mahmoud Kiamil Pasha, to talk with Phildius to develop a

specific plan. The Turkish secretary scheduled a meeting the next day at the War Office between Phildius and two representatives

of the Ministry of War and two delegates from the Red Crescent Society.28

29

The meeting at the Ministry of War on January 31 included Major Dr. Refik Bey (representing the Sanitary Section of the War

Office), Major Kiemal Bey, (Director of the War Prisoners' Section of the War Office), Dr. Bessim Omer Pasha (Vice President

of the Red Crescent Society), and Izzet Dey (Chief of the War Prisoners' Department of the Red Crescent Society). Phildius

prepared a memorandum in French on the history of the World's Alliance of YMCAs and WPA activities in the Central Power and

Allied nations, and made a specific offer of Association services to the Turkish government. Phildius also included a deadline

for an official reply, February 16, because he planned to leave soon for Geneva via the Balkans. He then discussed the POW

situation in Allied countries with Turkish POWs. During the meeting, Phildius outlined the services WPA secretaries provided

and the privileges they enjoyed. He then offered the services of three neutral secretaries in the Ottoman Empire. The group

discussed Phildius' memo point by point. Refik Bey was especially interested in this document, and promised to do everything

in his power to get an official reply from Enver Pasha as soon as possible.29

The meeting at the Ministry of War on January 31 included Major Dr. Refik Bey (representing the Sanitary Section of the War

Office), Major Kiemal Bey, (Director of the War Prisoners' Section of the War Office), Dr. Bessim Omer Pasha (Vice President

of the Red Crescent Society), and Izzet Dey (Chief of the War Prisoners' Department of the Red Crescent Society). Phildius

prepared a memorandum in French on the history of the World's Alliance of YMCAs and WPA activities in the Central Power and

Allied nations, and made a specific offer of Association services to the Turkish government. Phildius also included a deadline

for an official reply, February 16, because he planned to leave soon for Geneva via the Balkans. He then discussed the POW

situation in Allied countries with Turkish POWs. During the meeting, Phildius outlined the services WPA secretaries provided

and the privileges they enjoyed. He then offered the services of three neutral secretaries in the Ottoman Empire. The group

discussed Phildius' memo point by point. Refik Bey was especially interested in this document, and promised to do everything

in his power to get an official reply from Enver Pasha as soon as possible.29

30

While waiting for an official Turkish response, Phildius developed contacts with the Red Crescent Society and the diplomatic

community in Constantinople. He met with Turkey's allies, the German and Austro-Hungarian ambassadors and the Bulgarian minister.

In addition, Phildius met with the Dutch, Spanish, and Swedish ministers who represented Allied interests in the Ottoman Empire.

Phildius wanted to lay a stronger diplomatic foundation for future negotiations if the Ottoman government failed to respond to

his proposal before his departure date.30

While waiting for an official Turkish response, Phildius developed contacts with the Red Crescent Society and the diplomatic

community in Constantinople. He met with Turkey's allies, the German and Austro-Hungarian ambassadors and the Bulgarian minister.

In addition, Phildius met with the Dutch, Spanish, and Swedish ministers who represented Allied interests in the Ottoman Empire.

Phildius wanted to lay a stronger diplomatic foundation for future negotiations if the Ottoman government failed to respond to

his proposal before his departure date.30

31

Two weeks after the Ministry of War meeting, Refik Bey telephoned Phildius and told him that he could expect an official

reply the next day. On February 14, Phildius received authorization for YMCA WPA work in the Ottoman Empire from Major Kiemal

Bey, in the name of Enver Pasha. Under this order, the World's Alliance gained a number of privileges, including the appointment

of three neutral secretaries; visitation to all the camps, working detachments (including the Baghdad and other railroad

projects), and hospitals where POWs were located; free transportation of WPA goods; permission to accept requests from prisoners

for transmission to the War Prisoners' Section of the Ministry of War; distribution of money, extra food, clothing, and medicine

to needy POWs; construction of huts in convenient places, equipped with reading and writing rooms, libraries (which included the

Holy Scriptures), and games, plus permission to organize concerts, cinematographic performances, and religious services; and

permission to arrange workshops for the manufacture of small articles by POWs to be sold for their benefit. Major Kiemal Bey

expressly stated that Enver Pasha officially sanctioned this agreement, and that the War Prisoners' Section of the Ministry

of War would extend every necessary assistance to the YMCA in conducting this POW relief.31

Two weeks after the Ministry of War meeting, Refik Bey telephoned Phildius and told him that he could expect an official

reply the next day. On February 14, Phildius received authorization for YMCA WPA work in the Ottoman Empire from Major Kiemal

Bey, in the name of Enver Pasha. Under this order, the World's Alliance gained a number of privileges, including the appointment

of three neutral secretaries; visitation to all the camps, working detachments (including the Baghdad and other railroad

projects), and hospitals where POWs were located; free transportation of WPA goods; permission to accept requests from prisoners

for transmission to the War Prisoners' Section of the Ministry of War; distribution of money, extra food, clothing, and medicine

to needy POWs; construction of huts in convenient places, equipped with reading and writing rooms, libraries (which included the

Holy Scriptures), and games, plus permission to organize concerts, cinematographic performances, and religious services; and

permission to arrange workshops for the manufacture of small articles by POWs to be sold for their benefit. Major Kiemal Bey

expressly stated that Enver Pasha officially sanctioned this agreement, and that the War Prisoners' Section of the Ministry

of War would extend every necessary assistance to the YMCA in conducting this POW relief.31

32

The Turkish Ministry of War extended these privileges on the condition that the World's Alliance obtain official documents

from enemy governments listing the privileges granted to WPA secretaries conducting relief work for Turkish POWs. The degree

of service allowed in the Ottoman Empire for Allied prisoners was directly related to the level of operations undertaken for

Turkish POWs in Allied camps. Phildius did not consider this "condition" too onerous, and as soon as he reached Geneva he

contacted the senior secretaries in the Allied countries to procure official documents.32

The Turkish Ministry of War extended these privileges on the condition that the World's Alliance obtain official documents

from enemy governments listing the privileges granted to WPA secretaries conducting relief work for Turkish POWs. The degree

of service allowed in the Ottoman Empire for Allied prisoners was directly related to the level of operations undertaken for

Turkish POWs in Allied camps. Phildius did not consider this "condition" too onerous, and as soon as he reached Geneva he

contacted the senior secretaries in the Allied countries to procure official documents.32

33

Once the YMCA had fulfilled the official document requirement, the Turkish Ministry of War would appoint a special commission,

including one or two representatives from the War Office and the Red Crescent Society; these representatives would accompany

WPA secretaries during their visits to prison camps. Phildius accepted this requirement as well, since it would allow Association

secretaries to visit prison compounds and labor detachments scattered throughout the Turkish interior, and it would give the

secretaries an "official" status, an important consideration when dealing with prison commandants and minor Ottoman government

officials. In addition, travel for WPA secretaries would be rendered both easier and safer. Turkey was rampant with brigands who