Table of Contents

Chapter 8

Instituting the Association's Four-fold Program in Prison Camps: From Saving the POW's Soul to "Keeping Body and Soul Together"

1

The Association program that Archibald C. Harte introduced and expanded in German prison camps was based on the "Four-fold" Program

developed by the American YMCA before the war. The Association sought to improve young men, concentrating on the development of social,

educational, religious, and physical skills to promote sound minds and bodies. The organization's inverted Red Triangle symbol reflected

the three principles of the YMCA's welfare objectives: development of the body, mind, and spirit (the inverted triangle was supported by

invisible hands, which indicated the Christian basis of the organization rather than depicting a standard triangle standing firmly on the

ground).

The Association program that Archibald C. Harte introduced and expanded in German prison camps was based on the "Four-fold" Program

developed by the American YMCA before the war. The Association sought to improve young men, concentrating on the development of social,

educational, religious, and physical skills to promote sound minds and bodies. The organization's inverted Red Triangle symbol reflected

the three principles of the YMCA's welfare objectives: development of the body, mind, and spirit (the inverted triangle was supported by

invisible hands, which indicated the Christian basis of the organization rather than depicting a standard triangle standing firmly on the

ground).

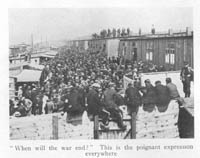

American and neutral WPA field secretaries established social and welfare services for war prisoners that reflected various dimensions

of the Association's program. By the third year of the war, secretaries recognized the problems of troops who lived under military orders

twenty-four hours a day. Soldiers had no privacy in their barracks or tents, and they were removed from ordinary life. Troops in the field

did, however, receive regular passes, furloughs, and visits from time to time. These luxuries were not available to war prisoners. The POW

was surrounded by barbed-wire stockades, and rare walks took prisoners into hostile country. Correspondence was strictly limited and

controlled by censors. There was no privacy inside the prison camps, and POWs faced the possibility of starvation or insanity. Rather than

allowing POWs to wallow in self-pity and idleness, the YMCA saw incarceration as an opportunity for these men to improve themselves and to

leave the camps as better men for the experience.1

American and neutral WPA field secretaries established social and welfare services for war prisoners that reflected various dimensions

of the Association's program. By the third year of the war, secretaries recognized the problems of troops who lived under military orders

twenty-four hours a day. Soldiers had no privacy in their barracks or tents, and they were removed from ordinary life. Troops in the field

did, however, receive regular passes, furloughs, and visits from time to time. These luxuries were not available to war prisoners. The POW

was surrounded by barbed-wire stockades, and rare walks took prisoners into hostile country. Correspondence was strictly limited and

controlled by censors. There was no privacy inside the prison camps, and POWs faced the possibility of starvation or insanity. Rather than

allowing POWs to wallow in self-pity and idleness, the YMCA saw incarceration as an opportunity for these men to improve themselves and to

leave the camps as better men for the experience.1

Educational Programs

2

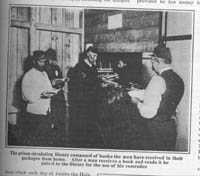

One of the best means to combat boredom in prison camps was the prison camp library. Not only did books provide light entertainment to

divert POWs' minds from their incarceration, but prisoners could also continue their studies or expand their skills through academic

and professional texts. The American YMCA, the German YMCA, and the World's Alliance of YMCAs focused their resources on obtaining books

for prison camp libraries. Several problems were associated with book acquisition. The supply of books in Slavic tongues was extremely

limited for Central Power POWs in Allied prison camps. For Allied prisoners in German prison camps, however, there does not appear to

have been as great a shortage of books in their native tongues. While books in Russian, Indian dialects, and Arabic may have been in short supply,

the level of literacy of prisoners from areas where these languages were spoken was often relatively low, and thus the demand for books

was limited.2

One of the best means to combat boredom in prison camps was the prison camp library. Not only did books provide light entertainment to

divert POWs' minds from their incarceration, but prisoners could also continue their studies or expand their skills through academic

and professional texts. The American YMCA, the German YMCA, and the World's Alliance of YMCAs focused their resources on obtaining books

for prison camp libraries. Several problems were associated with book acquisition. The supply of books in Slavic tongues was extremely

limited for Central Power POWs in Allied prison camps. For Allied prisoners in German prison camps, however, there does not appear to

have been as great a shortage of books in their native tongues. While books in Russian, Indian dialects, and Arabic may have been in short supply,

the level of literacy of prisoners from areas where these languages were spoken was often relatively low, and thus the demand for books

was limited.2

3

The greatest challenge to American secretaries attempting to purchase books for prison camp libraries was meeting German censorship

requirements. The censors passed only pre-war books that did not address politically sensitive issues. Working through the German

legation in Bern, the Association established an extensive book exchange system for POWs.

The greatest challenge to American secretaries attempting to purchase books for prison camp libraries was meeting German censorship

requirements. The censors passed only pre-war books that did not address politically sensitive issues. Working through the German

legation in Bern, the Association established an extensive book exchange system for POWs.

Books for French prisoners in Germany were collected in France, and books for German POWs in France were obtained in Germany and passed

through Switzerland. The German government provided a considerable sum of money for this exchange program, and the YMCA distributed the

French books in Germany. Student prisoners in German POW camps checked off the books they desired from an approved list of textbooks,

and the American YMCA provided these texts. The success of this program led to the establishment of similar exchange programs in Britain

and Russia with Germany.3

Books for French prisoners in Germany were collected in France, and books for German POWs in France were obtained in Germany and passed

through Switzerland. The German government provided a considerable sum of money for this exchange program, and the YMCA distributed the

French books in Germany. Student prisoners in German POW camps checked off the books they desired from an approved list of textbooks,

and the American YMCA provided these texts. The success of this program led to the establishment of similar exchange programs in Britain

and Russia with Germany.3

4

The American YMCA had the most difficult time obtaining books in Russian for POWs in Germany. During the early part of the war, there

was an acute shortage of these books. By September 1916, however, the Association was able to supply a total of 306,000 Russian texts

and Scriptures directly to Russian prisoners. The YMCA also provided 56,700 Russian books to prison camp and hospital libraries. The

most direct approach to solving the book shortage was for the Association to print Russian texts.

The American YMCA had the most difficult time obtaining books in Russian for POWs in Germany. During the early part of the war, there

was an acute shortage of these books. By September 1916, however, the Association was able to supply a total of 306,000 Russian texts

and Scriptures directly to Russian prisoners. The YMCA also provided 56,700 Russian books to prison camp and hospital libraries. The

most direct approach to solving the book shortage was for the Association to print Russian texts.

In 1916, the German YMCA began publishing elementary Russian textbooks, while the American YMCA set up a Russian publishing firm in

Bern, Switzerland. The shortage was further relieved by a shipment of 110 small libraries by Princess Helen of Altenburg from Russia

as her personal contribution to Russian war prisoners.4 The American YMCA also

scoured German bookstores for works in a wide range of Allied tongues. Between 1 August and 1 October 1917, the WPA Headquarters in

Berlin shipped out 96,914 books in seventeen different languages, including Tartar, Turkish, Flemish, Finnish, Estonian, English,

French, Russian, Romanian, Serbian, and Armenian. In addition, the World's Committee published a monthly magazine, The Messenger

to the Prisoners of War, specifically for war prisoners.

In 1916, the German YMCA began publishing elementary Russian textbooks, while the American YMCA set up a Russian publishing firm in

Bern, Switzerland. The shortage was further relieved by a shipment of 110 small libraries by Princess Helen of Altenburg from Russia

as her personal contribution to Russian war prisoners.4 The American YMCA also

scoured German bookstores for works in a wide range of Allied tongues. Between 1 August and 1 October 1917, the WPA Headquarters in

Berlin shipped out 96,914 books in seventeen different languages, including Tartar, Turkish, Flemish, Finnish, Estonian, English,

French, Russian, Romanian, Serbian, and Armenian. In addition, the World's Committee published a monthly magazine, The Messenger

to the Prisoners of War, specifically for war prisoners.

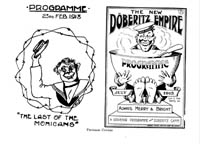

The World's Alliance published editions in English, French, Russian, and Italian, and these journals were freely distributed in German

prison camps. The YMCA also helped support prison camp newspapers in many POW camps, including The Wooden City: A Journal for British

Prisoners of War in Göttingen; Le Camp de Göttingen: Les Manuscripts non inseres ne sont pas rendus, also in

Göttingen; The Barbed Wireless in Rastatt; The Rembahn Review in Münster II; The Döberitz Empire in

Döberitz; and In Ruhleben Camp in Ruhleben. These newspapers gave prisoners a chance to liven up social life in the stockades, spread some

gossip, and improve morale.5

The World's Alliance published editions in English, French, Russian, and Italian, and these journals were freely distributed in German

prison camps. The YMCA also helped support prison camp newspapers in many POW camps, including The Wooden City: A Journal for British

Prisoners of War in Göttingen; Le Camp de Göttingen: Les Manuscripts non inseres ne sont pas rendus, also in

Göttingen; The Barbed Wireless in Rastatt; The Rembahn Review in Münster II; The Döberitz Empire in

Döberitz; and In Ruhleben Camp in Ruhleben. These newspapers gave prisoners a chance to liven up social life in the stockades, spread some

gossip, and improve morale.5

5

The Deutsche Christlicher Studentenvereinigungen (German Christian Student Union or DCSV) also played an important role in the POW book exchange program. The initial

concern of Dr. Gerhard Niedermeyer and other Student Christian leaders was the welfare of German academics imprisoned in Russia. They

provided these POWs with scholarly textbooks as Liebesgaben (charitable gifts) and Harte developed an exchange system with the

Russian government. In the meantime, the DCSV began to collect and distribute professional literature for French, Russian, and English

POWs in German prison camps. The Ministry of War approved this plan, which allowed students to continue their studies. The DCSV

systematically set up libraries of technical books in several prison camps. The DCSV also collected German professional texts for German

POWs in Allied prison camps, and was soon sending large consignments of books to prisoners in France and England. In conjunction with the

American YMCA, the DCSV drew up wish-lists, which allowed academics to request special books required for their studies and research. The

DCSV estimated that their program assisted approximately twenty thousand academics in continuing their research during their incarceration. By the

spring of 1916, the American YMCA had received permission from the Russian government for the DCSV to prepare libraries for German POWs

in European Russia and Siberia. The DCSV immediately sent three hundred libraries containing three hundred volumes in each set to Russia for use by students

in POW camps. Thousands of books were to follow this initial shipment. However, this exchange program was not without problems. Under

Russian regulations, bindings on books had to be removed prior to shipment to facilitate censorship inspection. As a result, the Association

had to send along binding material, cardboard, cloth, and paste, so that the POWs could rebind the books once they received a

shipment.6

The Deutsche Christlicher Studentenvereinigungen (German Christian Student Union or DCSV) also played an important role in the POW book exchange program. The initial

concern of Dr. Gerhard Niedermeyer and other Student Christian leaders was the welfare of German academics imprisoned in Russia. They

provided these POWs with scholarly textbooks as Liebesgaben (charitable gifts) and Harte developed an exchange system with the

Russian government. In the meantime, the DCSV began to collect and distribute professional literature for French, Russian, and English

POWs in German prison camps. The Ministry of War approved this plan, which allowed students to continue their studies. The DCSV

systematically set up libraries of technical books in several prison camps. The DCSV also collected German professional texts for German

POWs in Allied prison camps, and was soon sending large consignments of books to prisoners in France and England. In conjunction with the

American YMCA, the DCSV drew up wish-lists, which allowed academics to request special books required for their studies and research. The

DCSV estimated that their program assisted approximately twenty thousand academics in continuing their research during their incarceration. By the

spring of 1916, the American YMCA had received permission from the Russian government for the DCSV to prepare libraries for German POWs

in European Russia and Siberia. The DCSV immediately sent three hundred libraries containing three hundred volumes in each set to Russia for use by students

in POW camps. Thousands of books were to follow this initial shipment. However, this exchange program was not without problems. Under

Russian regulations, bindings on books had to be removed prior to shipment to facilitate censorship inspection. As a result, the Association

had to send along binding material, cardboard, cloth, and paste, so that the POWs could rebind the books once they received a

shipment.6

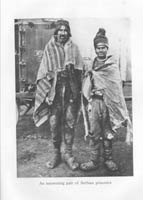

6

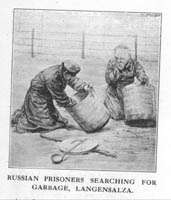

Another key component of the Association's program to improve the mental condition of POWs was the introduction of education systems

in prison camps. Education service varied greatly, depending on the backgrounds of the prisoners. A large percentage of Russian and

Serbian POWs were illiterate and were interested in learning how to read (Conrad Hoffman estimated the illiteracy rate among these

prisoners at between 75 and 85 percent).

Another key component of the Association's program to improve the mental condition of POWs was the introduction of education systems

in prison camps. Education service varied greatly, depending on the backgrounds of the prisoners. A large percentage of Russian and

Serbian POWs were illiterate and were interested in learning how to read (Conrad Hoffman estimated the illiteracy rate among these

prisoners at between 75 and 85 percent).

The Senior Secretary discovered that approximately 60 percent of the Italian prisoners in German POW camps were illiterate as well.

The YMCA emphasized to these prisoners the importance of learning how to read. The most immediate benefit of reading and writing

classes for illiterate POWs was their ability to write and receive letters from loved ones at home.

The Senior Secretary discovered that approximately 60 percent of the Italian prisoners in German POW camps were illiterate as well.

The YMCA emphasized to these prisoners the importance of learning how to read. The most immediate benefit of reading and writing

classes for illiterate POWs was their ability to write and receive letters from loved ones at home.

This was a great source of joy for these men. By spending their time in captivity studying basic math and reading skills, these men

could return home, get better jobs, and improve their families' standard of living. At Worms, Carl T. Michel found over one hundred

illiterate Russians in a single company, and immediately set up a school with the support of the camp commandant. Camp officials

provided rooms for classes, and the American YMCA provided textbooks. Michel reported that over 150 students enrolled when the school

was opened.7

This was a great source of joy for these men. By spending their time in captivity studying basic math and reading skills, these men

could return home, get better jobs, and improve their families' standard of living. At Worms, Carl T. Michel found over one hundred

illiterate Russians in a single company, and immediately set up a school with the support of the camp commandant. Camp officials

provided rooms for classes, and the American YMCA provided textbooks. Michel reported that over 150 students enrolled when the school

was opened.7

7

Association schools also catered to more advanced students. While the YMCA provided equipment to operate schools, the prisoners provided

the labor to run the classes. Field secretaries sought volunteers from among the camp population who had experience as teachers, professors,

or professionals to teach eager students. With the assistance of the secretary, the POWs formed an Education Committee as part of their

camp's Association. Then the WPA Headquarters sent textbooks, office supplies, musical instruments, laboratory equipment, tools, and

other necessary support. Sometimes schools started in the open air, but most camp commandants provided rooms, if not buildings, for

YMCA-sponsored classes. The courses offered reflected the expertise of the prisoners in the camp. Most Association schools offered a

variety of foreign languages, business skills, sciences, literature, mathematics, and vocational education.

Association schools also catered to more advanced students. While the YMCA provided equipment to operate schools, the prisoners provided

the labor to run the classes. Field secretaries sought volunteers from among the camp population who had experience as teachers, professors,

or professionals to teach eager students. With the assistance of the secretary, the POWs formed an Education Committee as part of their

camp's Association. Then the WPA Headquarters sent textbooks, office supplies, musical instruments, laboratory equipment, tools, and

other necessary support. Sometimes schools started in the open air, but most camp commandants provided rooms, if not buildings, for

YMCA-sponsored classes. The courses offered reflected the expertise of the prisoners in the camp. Most Association schools offered a

variety of foreign languages, business skills, sciences, literature, mathematics, and vocational education.

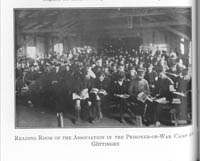

Prison camps often had over one thousand students attending the Association school; advanced students did not want to waste time during their

incarceration. The Germans exempted imprisoned university students from labor detachments, which allowed them to continue their studies.

Through the American YMCA, the prison camps at Ruhleben, Göttingen, Heidelberg, Dresden, Cottbus, and Villingen established special

relationships with professors at neighboring universities. Professors agreed to teach classes and give lectures to advanced students.

These universities and the Royal Library in Berlin even extended book-borrowing privileges to war prisoners. Advanced students also

received special consideration from German officials. Forty-five French officers conducted scientific research in prison camps using

equipment provided by the YMCA. Lieutenant Dr. Beszenoff, a Russian bacteriologist before the war, worked in a special laboratory in

Frankfurt-am-Main during the war.8

Prison camps often had over one thousand students attending the Association school; advanced students did not want to waste time during their

incarceration. The Germans exempted imprisoned university students from labor detachments, which allowed them to continue their studies.

Through the American YMCA, the prison camps at Ruhleben, Göttingen, Heidelberg, Dresden, Cottbus, and Villingen established special

relationships with professors at neighboring universities. Professors agreed to teach classes and give lectures to advanced students.

These universities and the Royal Library in Berlin even extended book-borrowing privileges to war prisoners. Advanced students also

received special consideration from German officials. Forty-five French officers conducted scientific research in prison camps using

equipment provided by the YMCA. Lieutenant Dr. Beszenoff, a Russian bacteriologist before the war, worked in a special laboratory in

Frankfurt-am-Main during the war.8

8

The YMCA was also concerned with the large number of boys in German prison camps. When fathers received their mobilization orders for

the Russian and Serbian armies, many of their under-aged sons joined them in the ranks and followed them into captivity. A large number

of the young prisoners had run away from home to join the army-they wanted to drop out of school and join the great adventure.

The YMCA was also concerned with the large number of boys in German prison camps. When fathers received their mobilization orders for

the Russian and Serbian armies, many of their under-aged sons joined them in the ranks and followed them into captivity. A large number

of the young prisoners had run away from home to join the army-they wanted to drop out of school and join the great adventure.

William Lawall noted the presence of these boys in most of the prison camps he visited. Most lacked supervision and were learning a

variety of vices from the older soldiers. Due to their age and military experience, the Germans refused to exchange or repatriate

these boys, since they could return to the ranks.

William Lawall noted the presence of these boys in most of the prison camps he visited. Most lacked supervision and were learning a

variety of vices from the older soldiers. Due to their age and military experience, the Germans refused to exchange or repatriate

these boys, since they could return to the ranks.

As a result, Lawall approached the Ministry of War and recommended that all the youngsters in German prison camps be concentrated in

one facility where the Association could set up a program for them. German officials welcomed the proposal, and the YMCA received the

support of a Russian physician. The Germans had found these boys difficult to control and agreed that they should be segregated from

the older men. By the fall of 1916, the Ministry of War decided to send the boys to Hammerstein, and asked the American YMCA to set

up a school for them. These boys now had the opportunity to learn a trade so they could be gainfully employed once they returned home

after the war. The American YMCA assumed responsibility for over 1,500 boys incarcerated at Hammerstein.9

As a result, Lawall approached the Ministry of War and recommended that all the youngsters in German prison camps be concentrated in

one facility where the Association could set up a program for them. German officials welcomed the proposal, and the YMCA received the

support of a Russian physician. The Germans had found these boys difficult to control and agreed that they should be segregated from

the older men. By the fall of 1916, the Ministry of War decided to send the boys to Hammerstein, and asked the American YMCA to set

up a school for them. These boys now had the opportunity to learn a trade so they could be gainfully employed once they returned home

after the war. The American YMCA assumed responsibility for over 1,500 boys incarcerated at Hammerstein.9

9

Another special target group for Association education programs was seriously wounded and invalid prisoners. Most of these men would

not be able to return to their pre-war trades. When they returned home without any means of making a living, they would be a burden on

their communities; their families would suffer a lowered standard of living, since their primary bread-winner would no longer be

employed.

Another special target group for Association education programs was seriously wounded and invalid prisoners. Most of these men would

not be able to return to their pre-war trades. When they returned home without any means of making a living, they would be a burden on

their communities; their families would suffer a lowered standard of living, since their primary bread-winner would no longer be

employed.

To avoid this, the YMCA strove to rehabilitate these prisoners by building up their physical condition and teaching them new skills.

First, YMCA secretaries encouraged the POWs to play sports (especially volleyball) and exercise through gymnastics. Physical activity

helped these men recuperate in the fresh air, regain some use of their wounded limbs, and learn how to accommodate their new disabilities.

Lawall was instrumental in organizing Association invalid programs. At Hammerstein, Lawall established a school for crippled Russian

prisoners in the summer of 1916. Approximately 85 percent of these men had been farmers before the war and would no longer be able to

work in the fields.

To avoid this, the YMCA strove to rehabilitate these prisoners by building up their physical condition and teaching them new skills.

First, YMCA secretaries encouraged the POWs to play sports (especially volleyball) and exercise through gymnastics. Physical activity

helped these men recuperate in the fresh air, regain some use of their wounded limbs, and learn how to accommodate their new disabilities.

Lawall was instrumental in organizing Association invalid programs. At Hammerstein, Lawall established a school for crippled Russian

prisoners in the summer of 1916. Approximately 85 percent of these men had been farmers before the war and would no longer be able to

work in the fields.

At this school, invalids learned shoemaking and tailoring skills. He then set up an invalid school at Schütt in the fall of 1916. The

Germans assigned two thousand wounded and crippled Russian prisoners to this military hospital (the patient population had doubled by September

1917). At the Association school, these POWs learned to read, write, weave baskets, weave braid for straw hats, weave horse-hair for

watch chains, and carve wood. For the YMCA, invalid rehabilitation was an important component of post-war reconstruction.10

At this school, invalids learned shoemaking and tailoring skills. He then set up an invalid school at Schütt in the fall of 1916. The

Germans assigned two thousand wounded and crippled Russian prisoners to this military hospital (the patient population had doubled by September

1917). At the Association school, these POWs learned to read, write, weave baskets, weave braid for straw hats, weave horse-hair for

watch chains, and carve wood. For the YMCA, invalid rehabilitation was an important component of post-war reconstruction.10

Religious Services

10

Under the agreement with the German government, the American YMCA made no attempt to conduct sectarian religious services.

The Association did, however, promote spiritual relief among depressed prisoners. WPA field secretaries provided an

ecumenical service to POWs, opening the Association programs to all men, regardless of creed. YMCA huts were not only

open for Roman Catholic, Russian Orthodox, Jewish, and Muslim religious services, but space was specifically allocated

for separate altars for each religion. When not in use, Association officials partitioned these sacred areas off from

the general public to guarantee sanctity. For the general prison population, WPA secretaries offered non-sectarian

religious and moral talks, usually on Sunday evenings. They also organized Bible study groups for weekday evenings to

help prisoners translate religion into daily life. The field secretaries usually worked with the religion committee of

the camp Association and the German military authorities to invite civilian priests or rabbis to the prison, or to

support incarcerated clergy who could conduct services. These religion committees strove to increase attendance at

church services and maintain the church when ministers or the Association secretary were unavailable. Red Triangle

secretaries did lead Protestant church services for POWs in many prison camps (a large number of American secretaries

were ordained ministers). They also conducted evangelistic campaigns among the Protestant POWs, which were open to other

interested individuals. Hoffman and James E. Sprunger supervised a major revival at Ruhleben, and the Senior Secretary

conducted drives in other camps. On a rainy night at one prison, Hoffman held a meeting in a large tent that contained

British, French, and Russian POWs. Hoffman opened the evening with a moral talk and the singing of old Gospel songs.

French and Russian prisoners soon gained interest in the activity and joined the English POWs. The American secretary

remarked, "here it was unnecessary to 'go out to all nations and preach the Gospel,' for here all nations had come

together."11

Under the agreement with the German government, the American YMCA made no attempt to conduct sectarian religious services.

The Association did, however, promote spiritual relief among depressed prisoners. WPA field secretaries provided an

ecumenical service to POWs, opening the Association programs to all men, regardless of creed. YMCA huts were not only

open for Roman Catholic, Russian Orthodox, Jewish, and Muslim religious services, but space was specifically allocated

for separate altars for each religion. When not in use, Association officials partitioned these sacred areas off from

the general public to guarantee sanctity. For the general prison population, WPA secretaries offered non-sectarian

religious and moral talks, usually on Sunday evenings. They also organized Bible study groups for weekday evenings to

help prisoners translate religion into daily life. The field secretaries usually worked with the religion committee of

the camp Association and the German military authorities to invite civilian priests or rabbis to the prison, or to

support incarcerated clergy who could conduct services. These religion committees strove to increase attendance at

church services and maintain the church when ministers or the Association secretary were unavailable. Red Triangle

secretaries did lead Protestant church services for POWs in many prison camps (a large number of American secretaries

were ordained ministers). They also conducted evangelistic campaigns among the Protestant POWs, which were open to other

interested individuals. Hoffman and James E. Sprunger supervised a major revival at Ruhleben, and the Senior Secretary

conducted drives in other camps. On a rainy night at one prison, Hoffman held a meeting in a large tent that contained

British, French, and Russian POWs. Hoffman opened the evening with a moral talk and the singing of old Gospel songs.

French and Russian prisoners soon gained interest in the activity and joined the English POWs. The American secretary

remarked, "here it was unnecessary to 'go out to all nations and preach the Gospel,' for here all nations had come

together."11

11

They sang hymns, read passages from the Bible, and closed the meeting with the Lord's Prayer. Then Hoffman

offered the men hot chocolate and white bread for refreshments. He found the prison camps a fertile ground for

religious work. In addition, the WPA field secretaries provided Bibles and spiritual tracts to all Christian

prisoners.

They sang hymns, read passages from the Bible, and closed the meeting with the Lord's Prayer. Then Hoffman

offered the men hot chocolate and white bread for refreshments. He found the prison camps a fertile ground for

religious work. In addition, the WPA field secretaries provided Bibles and spiritual tracts to all Christian

prisoners.

The American YMCA worked closely with the World's Sunday School Association, which had provided three hundred thousand New

Testaments to POWs for the YMCA to distribute by July 1915. They then planned to get one million New Testaments

for POWs through a nickel campaign. Harte requested Gospels in English, French, Russian, and Flemish to meet

demand.12

The American YMCA worked closely with the World's Sunday School Association, which had provided three hundred thousand New

Testaments to POWs for the YMCA to distribute by July 1915. They then planned to get one million New Testaments

for POWs through a nickel campaign. Harte requested Gospels in English, French, Russian, and Flemish to meet

demand.12

12

The American YMCA focused a great deal of its religious work among the Orthodox POWs, particularly the Russian,

Serbian, and Romanian prisoners. While French and Italian POWs had ready access to German Roman Catholic priests,

the Orthodox prisoners were relatively isolated from spiritual comfort. Before the war, Mott had worked to gain

access to Orthodox nations-although with few tangible results-as part of the YMCA's campaign to "evangelize the

world in this generation."

The American YMCA focused a great deal of its religious work among the Orthodox POWs, particularly the Russian,

Serbian, and Romanian prisoners. While French and Italian POWs had ready access to German Roman Catholic priests,

the Orthodox prisoners were relatively isolated from spiritual comfort. Before the war, Mott had worked to gain

access to Orthodox nations-although with few tangible results-as part of the YMCA's campaign to "evangelize the

world in this generation."

From an Association perspective, working with Eastern European POWs in the Central Power prison camps offered the

opportunity to introduce the YMCA program at the grass roots level. While the secretaries hoped to imbue the

Association spirit in as many Russians as possible, and possibly even attract future secretaries (the YMCA recognized

that native secretaries were more readily accepted than foreign Red Triangle workers), their primary goal was to build

friendships and name recognition among these prisoners. When these men returned home, they would remember the

Association's work. In the future, when a Foreign Work secretary arrived in their hometowns, it was hoped that the

former POWs would welcome the organization and help get it started in Orthodox countries.13

From an Association perspective, working with Eastern European POWs in the Central Power prison camps offered the

opportunity to introduce the YMCA program at the grass roots level. While the secretaries hoped to imbue the

Association spirit in as many Russians as possible, and possibly even attract future secretaries (the YMCA recognized

that native secretaries were more readily accepted than foreign Red Triangle workers), their primary goal was to build

friendships and name recognition among these prisoners. When these men returned home, they would remember the

Association's work. In the future, when a Foreign Work secretary arrived in their hometowns, it was hoped that the

former POWs would welcome the organization and help get it started in Orthodox countries.13

13

The Association supported Russian Orthodox services in a number of important ways. Many Russian prisoners sent

in requests for religious mementos to the YMCA. The Petrograd WPA Office sent three hundred thousand icons and small crosses

donated by Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna to the Berlin office for distribution among Russian POWs in Germany. The

American YMCA also presented Russian Gospels and Scriptures to prisoners upon request. More importantly, the

Association supported Orthodox religious services in German prison camps by supplying Orthodox ritual books to

priests through the YMCA office in Stockholm. Through extensive diplomatic negotiations, the Association was able

to procure antimensia (special altar cloths essential for Orthodox church rituals). These cloths could not be

procured in Germany because they were required to be produced under strict religious standards.

The Association supported Russian Orthodox services in a number of important ways. Many Russian prisoners sent

in requests for religious mementos to the YMCA. The Petrograd WPA Office sent three hundred thousand icons and small crosses

donated by Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna to the Berlin office for distribution among Russian POWs in Germany. The

American YMCA also presented Russian Gospels and Scriptures to prisoners upon request. More importantly, the

Association supported Orthodox religious services in German prison camps by supplying Orthodox ritual books to

priests through the YMCA office in Stockholm. Through extensive diplomatic negotiations, the Association was able

to procure antimensia (special altar cloths essential for Orthodox church rituals). These cloths could not be

procured in Germany because they were required to be produced under strict religious standards.

The antimension had to be blessed by the Bishop of the Greek Church in Petrograd, and could not be touched by any

lay people once consecrated. But shipping antimensia to Germany for use in POW camps presented difficulties, since

German customs and censorship authorities insisted on examining all incoming packages. Such an investigation would

violate the sanctity of the altar cloths. The YMCA negotiated a solution to this dilemma. The Russian Holy Synod

agreed to bless and deliver a dozen antimensia in a carefully sealed package carried by a Russian Red Cross sister.

Hoffman met the sister at the frontier, accompanied by an Orthodox priest. The Russian clergyman opened the package

in the presence of German officials for visual inspection. Once approved, the cloths continued their journey to prison

camps, so that thousands of Orthodox prisoners could enjoy religious services.14

The antimension had to be blessed by the Bishop of the Greek Church in Petrograd, and could not be touched by any

lay people once consecrated. But shipping antimensia to Germany for use in POW camps presented difficulties, since

German customs and censorship authorities insisted on examining all incoming packages. Such an investigation would

violate the sanctity of the altar cloths. The YMCA negotiated a solution to this dilemma. The Russian Holy Synod

agreed to bless and deliver a dozen antimensia in a carefully sealed package carried by a Russian Red Cross sister.

Hoffman met the sister at the frontier, accompanied by an Orthodox priest. The Russian clergyman opened the package

in the presence of German officials for visual inspection. Once approved, the cloths continued their journey to prison

camps, so that thousands of Orthodox prisoners could enjoy religious services.14

14

Celebration of the Christmas season was another important facet of Association work on behalf of POWs in Germany.

The yuletide season fostered depression among the prisoners, who were far from home and yearned for their families.

Hoffman and Sprunger were limited in what they could accomplish for POWs during the first Christmas season of their

work in December 1915, but the expanded force of American secretaries strove to spread Christmas cheer to as many

prisoners as possible the following year.

Celebration of the Christmas season was another important facet of Association work on behalf of POWs in Germany.

The yuletide season fostered depression among the prisoners, who were far from home and yearned for their families.

Hoffman and Sprunger were limited in what they could accomplish for POWs during the first Christmas season of their

work in December 1915, but the expanded force of American secretaries strove to spread Christmas cheer to as many

prisoners as possible the following year.

Michel noted that, as the holidays approached, some men asked for passes to cross the border as presents, which

demonstrated they still had a sense of humor. Several Allied officers were willing to pay a small fortune for a

turkey or goose for their Christmas dinner, but such delicacies were becoming rare in Germany at any price. The WPA

Office in Berlin prepared well in advance for Christmas. The office workers sent out hundreds of entertainment boxes

to prison camps for distribution to labor detachments. Each box contained several games and one or two musical

instruments. The YMCA conducted a Christmas card design contest among the POWs, and the Association had 10,000 copies

of the winning entry printed. These cards were then distributed among the POWs to send back home. Thousands of other

Christmas cards followed for posting by the prisoners. The YMCA also had thousands of specially designed New Year's

cards produced for Russian and Polish prisoners. The WPA field secretary in Saxony, E. O. Jacob, conducted similar

operations for POWs in Saxon prison camps.15

Michel noted that, as the holidays approached, some men asked for passes to cross the border as presents, which

demonstrated they still had a sense of humor. Several Allied officers were willing to pay a small fortune for a

turkey or goose for their Christmas dinner, but such delicacies were becoming rare in Germany at any price. The WPA

Office in Berlin prepared well in advance for Christmas. The office workers sent out hundreds of entertainment boxes

to prison camps for distribution to labor detachments. Each box contained several games and one or two musical

instruments. The YMCA conducted a Christmas card design contest among the POWs, and the Association had 10,000 copies

of the winning entry printed. These cards were then distributed among the POWs to send back home. Thousands of other

Christmas cards followed for posting by the prisoners. The YMCA also had thousands of specially designed New Year's

cards produced for Russian and Polish prisoners. The WPA field secretary in Saxony, E. O. Jacob, conducted similar

operations for POWs in Saxon prison camps.15

15

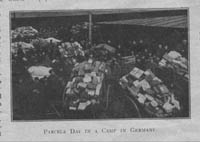

Foreign welfare agencies took advantage of the American WPA secretaries' direct contact with prisoners during the

Christmas season. Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden sent thousands of gifts and photo-cards with pictures of the

princess and her children with Christmas greetings to war prisoners recovering in infirmaries. A Russian countess

donated five hundred Marks to the American YMCA for secretaries to purchase sausage in Denmark for two hundred sick and crippled

Russian POWs in a military hospital in Berlin. Another man gave three thousand Marks, with which the Association bought

sausages and tea in Denmark for over six thousand Russian prisoners in another lazarette. On January 7, Orthodox Christmas

Day, American secretaries distributed these parcels along with other gifts. They also provided Christmas trees with

electric lights and a gramophone with Russian records for a concert. The Swedish and Norwegian National YMCA Councils

sent thousands of presents to needy Russian prisoners to remind them that they were remembered during the holidays. In

addition, relief organizations in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark sent thousands of individual parcels for the Association

to distribute among the more than three hundred refugee children at the internment camp at Holzminden in Prussia.16

Foreign welfare agencies took advantage of the American WPA secretaries' direct contact with prisoners during the

Christmas season. Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden sent thousands of gifts and photo-cards with pictures of the

princess and her children with Christmas greetings to war prisoners recovering in infirmaries. A Russian countess

donated five hundred Marks to the American YMCA for secretaries to purchase sausage in Denmark for two hundred sick and crippled

Russian POWs in a military hospital in Berlin. Another man gave three thousand Marks, with which the Association bought

sausages and tea in Denmark for over six thousand Russian prisoners in another lazarette. On January 7, Orthodox Christmas

Day, American secretaries distributed these parcels along with other gifts. They also provided Christmas trees with

electric lights and a gramophone with Russian records for a concert. The Swedish and Norwegian National YMCA Councils

sent thousands of presents to needy Russian prisoners to remind them that they were remembered during the holidays. In

addition, relief organizations in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark sent thousands of individual parcels for the Association

to distribute among the more than three hundred refugee children at the internment camp at Holzminden in Prussia.16

16

Individual secretaries did all they could to spread Christmas cheer. One American secretary hired an automobile

and played Santa Claus. He drove between working detachments in his region, giving gramophone concerts and distributing

books, pictures, games (chess, dominoes, lotto, and Halma), puzzles, mouth organs, Jews' harps, accordions, cigarettes,

chocolate, small parcels, and Christmas cards as presents. A senior Russian prisoner passed the hat to give the secretary

a small token of their appreciation as a Christmas present. Other secretaries purchased oranges and apples for the sick

prisoners they visited. They arranged special seasonal concerts, vaudeville performances, lantern-slide lectures, and

religious services. In several prison camps, the YMCA provided Christmas candles, trees, and bags of fruit. For example,

the WPA field secretary assigned to Württemberg supplied the Christmas trees for the Allied prisoners in the military

hospital in Stuttgart.

Individual secretaries did all they could to spread Christmas cheer. One American secretary hired an automobile

and played Santa Claus. He drove between working detachments in his region, giving gramophone concerts and distributing

books, pictures, games (chess, dominoes, lotto, and Halma), puzzles, mouth organs, Jews' harps, accordions, cigarettes,

chocolate, small parcels, and Christmas cards as presents. A senior Russian prisoner passed the hat to give the secretary

a small token of their appreciation as a Christmas present. Other secretaries purchased oranges and apples for the sick

prisoners they visited. They arranged special seasonal concerts, vaudeville performances, lantern-slide lectures, and

religious services. In several prison camps, the YMCA provided Christmas candles, trees, and bags of fruit. For example,

the WPA field secretary assigned to Württemberg supplied the Christmas trees for the Allied prisoners in the military

hospital in Stuttgart.

17

The candles that added the magical touch to Christmas trees were especially difficult for Hoffman to find for the

Christmas 1917 celebrations. Because fat had virtually disappeared from the German market by this time, candles were

a challenge to obtain. The Senior Secretary was able to procure over two thousand candles during the year, which permitted the

WPA Office in Berlin to send each prison camp in Germany a few candles. In addition, the YMCA sent wine and bread to

camps so that the POWs could celebrate High Mass during the Christmas services. The secretaries also promoted the Christmas

spirit among the incarcerated by encouraging Association Welfare Committees to remember the needy prisoners among them.

At Dyrotz, British POWs saved part of their food parcel supplies for several weeks as Christmas gifts for poor Russian

POWs. In an officers' camp, the men collected 7,500 Marks to purchase gifts for deserving privates in other prisons. At

Ruhleben, the internees collected four hundred pairs of woolen socks for poor Serbian POWs. The American YMCA distributed Christmas

presents to as many Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners as possible. In some camps, the Association set up a lottery

system where lucky POWs could win oranges, apples, gingerbread (Lebkuchen), cigarettes, Christmas cards, or

crucifixes. Serbian prisoners at Halbe appreciated the American YMCA's Christmas cheer, echoing the other POWs in their

fervent Christmas wishes for peace and the chance to return home.17

The candles that added the magical touch to Christmas trees were especially difficult for Hoffman to find for the

Christmas 1917 celebrations. Because fat had virtually disappeared from the German market by this time, candles were

a challenge to obtain. The Senior Secretary was able to procure over two thousand candles during the year, which permitted the

WPA Office in Berlin to send each prison camp in Germany a few candles. In addition, the YMCA sent wine and bread to

camps so that the POWs could celebrate High Mass during the Christmas services. The secretaries also promoted the Christmas

spirit among the incarcerated by encouraging Association Welfare Committees to remember the needy prisoners among them.

At Dyrotz, British POWs saved part of their food parcel supplies for several weeks as Christmas gifts for poor Russian

POWs. In an officers' camp, the men collected 7,500 Marks to purchase gifts for deserving privates in other prisons. At

Ruhleben, the internees collected four hundred pairs of woolen socks for poor Serbian POWs. The American YMCA distributed Christmas

presents to as many Russian, Serbian, and Romanian prisoners as possible. In some camps, the Association set up a lottery

system where lucky POWs could win oranges, apples, gingerbread (Lebkuchen), cigarettes, Christmas cards, or

crucifixes. Serbian prisoners at Halbe appreciated the American YMCA's Christmas cheer, echoing the other POWs in their

fervent Christmas wishes for peace and the chance to return home.17

18 Hoffman reported on his own efforts to spread Christmas cheer among the POWs in the vicinity of Berlin. On Christmas Eve in 1916, Hoffman and four Russian doctors visited a military hospital for Christmas celebrations. A sea of sick and wounded prisoners included English, French, and Russian men, along with one lonely Senegalese. Two Christmas trees with lighted candles were the highlight of the festivities. Hoffman described the scene:

One instinctively felt the effort being made to drive away those painful thoughts of the loved ones at home, to replace by temporary distraction the yearning in the hearts of many. For these men, there was no Christmas dinner. For many it was their third Christmas in prison.18

19

After the entertainment, Hoffman visited those POWs too sick to leave their beds. He wished he could have given them

eggs, milk, bread, or fruit, but the Allied blockade made these items too scarce. On Christmas Day, Hoffman took his

four-year old daughter, Louise, to visit Ruhleben. He never realized the "heart hunger" of these men until he saw

their response to the first child they had seen in almost three years. She ran around the Association hall and men

came from all over the camp to see the miracle of a child. Many cried, others stood in line for the chance to have her

sit on their laps, and most were able to forget the bitterness of imprisonment in the thoughts of their little ones at

home.19

After the entertainment, Hoffman visited those POWs too sick to leave their beds. He wished he could have given them

eggs, milk, bread, or fruit, but the Allied blockade made these items too scarce. On Christmas Day, Hoffman took his

four-year old daughter, Louise, to visit Ruhleben. He never realized the "heart hunger" of these men until he saw

their response to the first child they had seen in almost three years. She ran around the Association hall and men

came from all over the camp to see the miracle of a child. Many cried, others stood in line for the chance to have her

sit on their laps, and most were able to forget the bitterness of imprisonment in the thoughts of their little ones at

home.19

20

Christmas 1917 was even more difficult for Hoffman. The WPA program was hampered by the loss of American secretaries

after the United States entered the war and replacement secretaries from neutral nations were slow in arriving. As an

enemy alien, Hoffman no longer enjoyed unlimited prison camp visitation. All he could do was invite his Sunday School

class to his rooms for a little Christmas entertainment. He had saved enough sweets from his rations to give each guest

two pieces of candy, an apple, and a small piece of cake. He also put away cocoa and a can of condensed milk for the

celebrations (although his guests had to bring along their own cups). The Senior Secretary had a difficult time deciding

on gifts for his friends, especially since inflation had increased prices so much in Germany. "Old rubbish that had been

stored away for years was commanding staggering prices," he wrote. For Hoffman, December 1917 was a difficult Christmas,

since his hands were tied when POWs were in their greatest need.20

Christmas 1917 was even more difficult for Hoffman. The WPA program was hampered by the loss of American secretaries

after the United States entered the war and replacement secretaries from neutral nations were slow in arriving. As an

enemy alien, Hoffman no longer enjoyed unlimited prison camp visitation. All he could do was invite his Sunday School

class to his rooms for a little Christmas entertainment. He had saved enough sweets from his rations to give each guest

two pieces of candy, an apple, and a small piece of cake. He also put away cocoa and a can of condensed milk for the

celebrations (although his guests had to bring along their own cups). The Senior Secretary had a difficult time deciding

on gifts for his friends, especially since inflation had increased prices so much in Germany. "Old rubbish that had been

stored away for years was commanding staggering prices," he wrote. For Hoffman, December 1917 was a difficult Christmas,

since his hands were tied when POWs were in their greatest need.20

21

The American YMCA did not forget German guards during the Christmas season. Hoffman had a budget of two thousand Marks,

which the Association used to bring these men-"many just as lonely and homesick as the prisoners of war"-a little

Christmas joy. The YMCA distributed Christmas parcels to these lonely guards that included games, musical instruments,

and Christmas candles.

The Association also made sure that other German officials were not forgotten. The YMCA sent cigarettes to labor

detachment guards, and cigars to bureaucrats in administrative departments. While "Y" officials recognized that

maintaining good relations with German authorities was important, this service to guards during the holidays was

given in the spirit of the season.21

The American YMCA did not forget German guards during the Christmas season. Hoffman had a budget of two thousand Marks,

which the Association used to bring these men-"many just as lonely and homesick as the prisoners of war"-a little

Christmas joy. The YMCA distributed Christmas parcels to these lonely guards that included games, musical instruments,

and Christmas candles.

The Association also made sure that other German officials were not forgotten. The YMCA sent cigarettes to labor

detachment guards, and cigars to bureaucrats in administrative departments. While "Y" officials recognized that

maintaining good relations with German authorities was important, this service to guards during the holidays was

given in the spirit of the season.21

22

The American YMCA spared no expense to make the Christmas season as festive as possible for Allied POWs in Germany

during the war. For Christmas 1916, the Berlin WPA Office distributed 1,700 games, 1,650 candles and holders, 165

musical instruments, 4,500 cigarettes, and 1,100 cigars to POWs in prison camps across the breadth of the German

Empire. For the millions of Allied prisoners incarcerated across Germany, these gifts barely met their needs, although

the Association sought to supply presents that would benefit as many men as possible through Christmas tree decorations,

games, and music.

The American YMCA spared no expense to make the Christmas season as festive as possible for Allied POWs in Germany

during the war. For Christmas 1916, the Berlin WPA Office distributed 1,700 games, 1,650 candles and holders, 165

musical instruments, 4,500 cigarettes, and 1,100 cigars to POWs in prison camps across the breadth of the German

Empire. For the millions of Allied prisoners incarcerated across Germany, these gifts barely met their needs, although

the Association sought to supply presents that would benefit as many men as possible through Christmas tree decorations,

games, and music.

Due to the Allied blockade, Red Triangle secretaries found it difficult to obtain supplies that could be distributed

as Christmas presents, but prisoners appreciated even the smallest gifts as they passed through the Yuletide far from

family and friends. In December 1917, the American YMCA spent two hundred thousand Marks on Christmas supplies alone. Hoffman

recognized the Association's efforts were but "a drop in the bucket if all the prisoners of war were to be

reached."22

Due to the Allied blockade, Red Triangle secretaries found it difficult to obtain supplies that could be distributed

as Christmas presents, but prisoners appreciated even the smallest gifts as they passed through the Yuletide far from

family and friends. In December 1917, the American YMCA spent two hundred thousand Marks on Christmas supplies alone. Hoffman

recognized the Association's efforts were but "a drop in the bucket if all the prisoners of war were to be

reached."22

23

Another aspect of the Association's spiritual program was relief from mental anguish through communication between

POWs and their families. Under the Hague Agreements, POWs in Germany could send two letters a month and one postcard

per week from the camps, and were entitled to receive unrestricted correspondence. Letter writing was supported in a

number of ways. At a personal level, WPA field secretaries encouraged prisoners to write home by providing stationery

and postage-paid envelopes. They often visited hospitals and wrote letters home for incapacitated patients.

At Czersk, Lawall worked among three thousand sick and wounded Russian POWs and helped them communicate their situation to

Another aspect of the Association's spiritual program was relief from mental anguish through communication between

POWs and their families. Under the Hague Agreements, POWs in Germany could send two letters a month and one postcard

per week from the camps, and were entitled to receive unrestricted correspondence. Letter writing was supported in a

number of ways. At a personal level, WPA field secretaries encouraged prisoners to write home by providing stationery

and postage-paid envelopes. They often visited hospitals and wrote letters home for incapacitated patients.

At Czersk, Lawall worked among three thousand sick and wounded Russian POWs and helped them communicate their situation to

their families. Prisoners often feared that inaccurate information about their condition could cause their loved

ones unnecessary pain. A naval officer at Worms who had escaped the sinking of his warship was frantic because he

had received no news from home. Michel arranged to have a cable sent via the Netherlands to assure the officer's

family that he was safe. Secretaries provided letter-writing services to illiterate prisoners, but also encouraged

them to learn to read and write so they could correspond directly. At the national level, the YMCA maintained an

extensive POW information bureau in the belligerent nations' capitals. These administrative bodies provided POW

families with information regarding the physical condition and location of their incarcerated loved ones, and

offered services such as the transmission of money and correspondence. Maintaining contact with friends and family

helped POWs maintain a healthy mental attitude.23

their families. Prisoners often feared that inaccurate information about their condition could cause their loved

ones unnecessary pain. A naval officer at Worms who had escaped the sinking of his warship was frantic because he

had received no news from home. Michel arranged to have a cable sent via the Netherlands to assure the officer's

family that he was safe. Secretaries provided letter-writing services to illiterate prisoners, but also encouraged

them to learn to read and write so they could correspond directly. At the national level, the YMCA maintained an

extensive POW information bureau in the belligerent nations' capitals. These administrative bodies provided POW

families with information regarding the physical condition and location of their incarcerated loved ones, and

offered services such as the transmission of money and correspondence. Maintaining contact with friends and family

helped POWs maintain a healthy mental attitude.23

Social Services and Entertainment

24

Another important element of the Association's Four-fold Program was entertainment for POWs. Mental diversions

allowed POWs to temporarily forget about the situation they faced. Music was one of the most important parts of

this service. The American YMCA provided a variety of musical instruments and sheet music so that the POWs could

organize orchestras, bands, and choirs. Between March 1915 and June 1917, the American YMCA spent twenty thousand Marks on

musical instruments for POWs in Germany.

Once organized, bands, choruses, and orchestras provided evening performances for the POWs and the guards, as well

as music for religious services, at theatrical performances, and at funerals. Most camps had talented musicians

among the ranks who worked hard to develop the music programs. Not only did they lead the bands and orchestras,

Another important element of the Association's Four-fold Program was entertainment for POWs. Mental diversions

allowed POWs to temporarily forget about the situation they faced. Music was one of the most important parts of

this service. The American YMCA provided a variety of musical instruments and sheet music so that the POWs could

organize orchestras, bands, and choirs. Between March 1915 and June 1917, the American YMCA spent twenty thousand Marks on

musical instruments for POWs in Germany.

Once organized, bands, choruses, and orchestras provided evening performances for the POWs and the guards, as well

as music for religious services, at theatrical performances, and at funerals. Most camps had talented musicians

among the ranks who worked hard to develop the music programs. Not only did they lead the bands and orchestras,

they offered lessons to POWs, who were eager to learn how to play a variety of instruments. The prisoners could draw

up a wish list of instruments and musical scores and send it through the YMCA field secretary to the WPA Office in

Berlin. At Döberitz, the POWs organized the "Prisoners' International Orchestra," and the Association provided

a cornet, flute, French horn, violoncello, castanets, and a tambourine to fill out the orchestra.

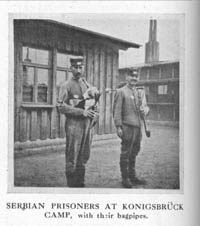

The Association sent an organ and stringed instruments to the officers' prison camp at Werl for Russian prisoners.

At Königsbrück in Saxony, Jacob equipped a Serbian gypsy orchestra, while Michel organized and

equipped an orchestra at Worms. The YMCA also provided sheet music for the chorus at Schneidemühl, which

allowed the prisoners to produce a show that greatly helped improve camp morale. Often, the musical talents of

field secretaries helped ease prisoners' suffering. Michel reported that POWs at Friedberg took special comfort

in his music. The benefits of music could even be extended to far-flung labor detachments by sending musical

instruments and scores to POWs at work sites. Michel pointed out that "music, especially singing, had charms to

soothe, cheer, and bless" the hapless prisoner of war.24

they offered lessons to POWs, who were eager to learn how to play a variety of instruments. The prisoners could draw

up a wish list of instruments and musical scores and send it through the YMCA field secretary to the WPA Office in

Berlin. At Döberitz, the POWs organized the "Prisoners' International Orchestra," and the Association provided

a cornet, flute, French horn, violoncello, castanets, and a tambourine to fill out the orchestra.

The Association sent an organ and stringed instruments to the officers' prison camp at Werl for Russian prisoners.

At Königsbrück in Saxony, Jacob equipped a Serbian gypsy orchestra, while Michel organized and

equipped an orchestra at Worms. The YMCA also provided sheet music for the chorus at Schneidemühl, which

allowed the prisoners to produce a show that greatly helped improve camp morale. Often, the musical talents of

field secretaries helped ease prisoners' suffering. Michel reported that POWs at Friedberg took special comfort

in his music. The benefits of music could even be extended to far-flung labor detachments by sending musical

instruments and scores to POWs at work sites. Michel pointed out that "music, especially singing, had charms to

soothe, cheer, and bless" the hapless prisoner of war.24

25

Handicrafts also diverted many prisoners from wasting idleness. The American YMCA provided tools and raw materials so that POWs in the

prison camps, military hospitals, and labor detachments could participate in wood carving, leather work, basket weaving,

carpentry, furniture making, book binding, needle work, toy making, flower arrangement, and a variety of other hobbies.

Handicrafts also diverted many prisoners from wasting idleness. The American YMCA provided tools and raw materials so that POWs in the

prison camps, military hospitals, and labor detachments could participate in wood carving, leather work, basket weaving,

carpentry, furniture making, book binding, needle work, toy making, flower arrangement, and a variety of other hobbies.

These crafts not only helped pass the time, but also improved prisoners' quality of life. The Association set up

workshops in prison camps, where trained artisans taught apprentices.

These trainees returned to civilian life with new skills and improved their families' living standards. Crown Princess

Margaret of Sweden arranged for an exhibition of POW handicrafts in Stockholm in

These crafts not only helped pass the time, but also improved prisoners' quality of life. The Association set up

workshops in prison camps, where trained artisans taught apprentices.

These trainees returned to civilian life with new skills and improved their families' living standards. Crown Princess

Margaret of Sweden arranged for an exhibition of POW handicrafts in Stockholm in

1916. At the end of the bazaar, the

articles were sold to the public, which gave the prisoners some additional income. The sale was scheduled to last for

three days, but it ended after the opening day because every article had been sold. The next year, POW handicraft

exhibitions followed in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.25

1916. At the end of the bazaar, the

articles were sold to the public, which gave the prisoners some additional income. The sale was scheduled to last for

three days, but it ended after the opening day because every article had been sold. The next year, POW handicraft

exhibitions followed in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.25

26

Association WPA field secretaries also played an important role in entertaining the POWs. The American YMCA provided

a wide range of equipment to ease the monotony in prison camps and hospitals. Secretaries carried gramophones and a

library of records so they could set up an impromptu gramophone concert on demand.

Association WPA field secretaries also played an important role in entertaining the POWs. The American YMCA provided

a wide range of equipment to ease the monotony in prison camps and hospitals. Secretaries carried gramophones and a

library of records so they could set up an impromptu gramophone concert on demand.

Stereopticons, radiopticons, and lantern slides also supported lectures on a wide variety of topics. Probably the

most popular of all YMCA entertainments was motion pictures.

Secretaries brought mobile motion picture projectors to camps, set up sheets on the side of a barrack, and showed

Stereopticons, radiopticons, and lantern slides also supported lectures on a wide variety of topics. Probably the

most popular of all YMCA entertainments was motion pictures.

Secretaries brought mobile motion picture projectors to camps, set up sheets on the side of a barrack, and showed

American movies in the open air for as many POWs as possible. When German authorities decided to encourage prisoners

to work on labor detachments by banning all amusements in the prison camps, it was a major blow to WPA secretaries,

but early in 1917 the Germans reversed their decision and again permitted motion picture performances.26

American movies in the open air for as many POWs as possible. When German authorities decided to encourage prisoners

to work on labor detachments by banning all amusements in the prison camps, it was a major blow to WPA secretaries,

but early in 1917 the Germans reversed their decision and again permitted motion picture performances.26

27

The Association hut was the center of social life in German prison camps. Most featured a game room where POWs played

a variety of games including chess, checkers, dominoes, Halma, cards, and lotto. The Entertainment Committee often

The Association hut was the center of social life in German prison camps. Most featured a game room where POWs played

a variety of games including chess, checkers, dominoes, Halma, cards, and lotto. The Entertainment Committee often

organized chess tournaments with prizes for the winners. These games helped prisoners

pass the time and cheered their

hearts. The POWs also set up organizations like debate clubs, which addressed important issues. The YMCA also provided

a great deal of support for theatrical societies in prison camps. Most Association halls had a stage, and the WPA Office

organized chess tournaments with prizes for the winners. These games helped prisoners

pass the time and cheered their

hearts. The POWs also set up organizations like debate clubs, which addressed important issues. The YMCA also provided

a great deal of support for theatrical societies in prison camps. Most Association halls had a stage, and the WPA Office

in Berlin sent scripts, costumes, and stage props to theater companies operated by Allied prisoners. Secretaries helped

organize stunt programs and comical performances in addition to serious dramatic presentations. Entertainment helped to

break the monotony of camp life and promoted a cheerful atmosphere, even if only for a short time.27

in Berlin sent scripts, costumes, and stage props to theater companies operated by Allied prisoners. Secretaries helped

organize stunt programs and comical performances in addition to serious dramatic presentations. Entertainment helped to

break the monotony of camp life and promoted a cheerful atmosphere, even if only for a short time.27

Physical Relief Services

28

The fourth pillar of the Association's program was physical fitness. This was especially important among POWs because

the maintenance of their health was the key to their survival during their incarceration. The physical element of the

Red Triangle program was based on athletic competition and exercise. The German authorities required POWs to participate

The fourth pillar of the Association's program was physical fitness. This was especially important among POWs because

the maintenance of their health was the key to their survival during their incarceration. The physical element of the

Red Triangle program was based on athletic competition and exercise. The German authorities required POWs to participate

in drill and gymnastic exercises, but the YMCA provided a wide range of athletic equipment so the men could also participate

in sports. WPA field secretaries provided soccer balls, tennis equipment, volleyballs, basketballs, ice skates, and baseball

equipment. The secretaries and athletic committees in the camps then organized teams and set up leagues, complete with

in drill and gymnastic exercises, but the YMCA provided a wide range of athletic equipment so the men could also participate

in sports. WPA field secretaries provided soccer balls, tennis equipment, volleyballs, basketballs, ice skates, and baseball

equipment. The secretaries and athletic committees in the camps then organized teams and set up leagues, complete with

championships and prizes. Field secretaries arranged with commandants to allow prisoners on parole to take walks outside

the camp barbed wire. Walking excursions were important not only from a physical perspective, but also promoted mental

health among the POWs by providing them a change of venue. During their prison camp visits, American secretaries sometimes

championships and prizes. Field secretaries arranged with commandants to allow prisoners on parole to take walks outside

the camp barbed wire. Walking excursions were important not only from a physical perspective, but also promoted mental

health among the POWs by providing them a change of venue. During their prison camp visits, American secretaries sometimes

recommended changes in prisoner exercise regimens because of deficient standards. At

Werl, Olandt reported that the space

for outdoor exercises was far too limited. He suggested to the camp commandant that German authorities rent a nearby walled

garden, which could serve as a tennis court or playground. The commandant accepted the recommendation, and French, British,

and Belgian officers were soon enjoying tennis matches. This exercise resulted in a decided improvement in their general

condition.28

recommended changes in prisoner exercise regimens because of deficient standards. At

Werl, Olandt reported that the space

for outdoor exercises was far too limited. He suggested to the camp commandant that German authorities rent a nearby walled

garden, which could serve as a tennis court or playground. The commandant accepted the recommendation, and French, British,

and Belgian officers were soon enjoying tennis matches. This exercise resulted in a decided improvement in their general

condition.28

29

Association secretaries also addressed the problems of sick prisoners. While this type of relief fell under the purview

of the Red Cross, the YMCA still took an interest in offering these men as much assistance as possible. WPA field

secretaries visited POWs in military hospitals and offered them entertainment, reading material, religious books,

cigarettes, and delicacies. Secretaries had dentists visit the camps; Michel had a prisoner's false teeth repaired

at Darmstadt, which helped the POW eat properly. Association secretaries also tried to procure special food and fruit

to augment the diets of sick prisoners. This was a difficult service because the Allied blockade caused a drastic food

shortage in Germany. Where food was available, it could be obtained only at high prices. As a result, secretaries

distributed oranges, apples, oatmeal, and bacon to ill POWs whenever such supplies were available. Secretaries also