1Like many settler women, Antoinetta Campher understood strategic marriage. Although she never found affluence, Antoinetta crafted kinship alliances and skillfully navigated serial widowhood to secure a place in the landscape for her family. Two Campher–van Wyk marriages followed her own, connecting households from Cape Town to the Olifants River, but the relationship that makes this association notable was illicit, not matrimonial. The mechanics of this family network emerge in an inadvertent traveler's tale, the day-by-day recollection of a journey from the Klawer Valley to Table Bay.

2In Antoinetta's time, long-distance travel in difficult terrain was commonplace for Cape residents, a necessity of colonial life and a longstanding feature of the area. Khoikhoi and San moved frequently and regularly throughout the region; they participated in trade that spanned the subcontinent.1 Colonial settlers—or their forebears—survived a three-month ocean voyage just to reach Table Bay, assuming the Cape was their first port of call. Many of the soldiers, sailors, and officials employed by the VOC who eventually settled at the Cape made at least one return voyage to the Indies, perhaps with a stay in Ceylon or Batavia. In that context, a five-day walk beside an ox wagon or a four-hour journey on horseback to pay a social call—with the return trip made the same day—was not an unreasonable expectation or an uncommon occurrence.2

3Published narratives illuminate the traveling patterns of visitors to the Cape, but only by inference do they describe the more quotidian movements of ordinary residents. Anders Sparrman's account, for example, suggests wagons and oxen were available to those with the means to pay.3 The existence of a resale market for wagons and spans of oxen implies a common presumption of travel and the necessity of moving heavy loads. The ready availability of existing wagons and full teams of oxen meant that travel with goods or provisions was not limited to farmers with adequate equipment and herds of their own. If few people were going to travel other than established farmers, it would not have been practical for anyone to maintain extra wagons and oxen. If Anders Sparrman could easily procure such materiel at various points in his journey, we can assume that equipment, livestock, and provisions were available to others.

4The further Sparrman got from Cape Town, however, the more difficulty he had procuring the services of a driver and guide.4 He was not hampered by lack of equipment or provisions, but rather by the disinclination of either settlers or Khoisan to undertake a long journey without necessity. The wide dispersion of people across the Cape region, the existence of settler farms at 14 to 20 days' travel from Cape Town,5 and evidence of intra-African long-distance trade all indicate that people did travel great distances with some regularity. The difficulty experienced by Sparrman and others in obtaining guides and drivers suggests that the locals did not, however, travel for recreation.6

5Eighteenth-century travelers such as Otto Mentzel, Carl Thunberg, and Anders Sparrman left copious written narratives and extensive scientific catalogs of their expeditions in Southern Africa, but travel as a matter of course is not equally well documented.7 In order to recover the movements of ordinary inhabitants of the Cape we must turn to archaeological material, oblique documentary references, and circumstantial evidence to piece together the specific movements of individuals and families. Such a reconstruction demonstrates the effectiveness of colonial kin networks and shows that stock-farming households were not isolated entities. Ordinary travels tied frontier areas closely to the settlement at Table Bay. The mechanics of this travel underscore the importance of land tenure and land use in creating effective colonial control across great distances with limited official presence.8

6All of the available source material on the early Western Cape points to ongoing mobility. Shell middens testify to Khoisan seasonal migrations. Glass beads connect the Cape to the Indian Ocean before the Portuguese did. Post rocks, monumental crosses, and later signal flags tied the southern African littoral to European seafaring empires. After the Dutch East India Company decided to erect a permanent presence in the region, archival practices arrived that enshrined some movements while effacing others. This documentary legacy, including official records as well as travel narratives, foregrounds settlers while Khoisan move like shadows across the landscape.

|

Cross Reference:

Valentijn, Lijs and Elsje moved from the Olifants River to Franschoek. |

Cross Reference:

Presumed, unnamed labor inhabits many colonial tales. |

7Although specific evidence of Khoisan movements is sporadic, the ripples it created are in the background of every settler-focused story. The historian and writer Karel Schoeman evokes this certainty in a novel set on the northern frontier: "Of the herdsmen, however, I remember nothing . . . I only know that they were always around somewhere . . . so that one accepted their constant presence without taking any further notice of them."9 So the documented migration of individuals such as Titus Valentijn, Lijs, and Elsje Abrahamse from the Olifants River to Franschoek was an archival anomaly, an uncharacteristic recording of movements otherwise considered too ordinary to remark upon. This understated presence, like presumed but unnamed labor, permeates the saga linking Camphers and van Wyks.

^topThe Journey Caabwaards

8Autumn at the Cape was busy; plowing and sowing demanded the full effort of agrarian communities. Slaves, indentured servants, and able-bodied sons worked the land of the farms on which they lived and often gave help to neighbors and relatives as well. Willem van Wyk was a stock farmer, so he had no large fields of grain to tend.10 His farm in the Klawer Valley undoubtedly had a kitchen garden, but the Kleinfontein household apparently could spare his labor, so during the plowing season in 1742, Willem set off in an ox wagon to take his sister-in-law to Cape Town.11 Sixteen-year-old Jacoba Alida Campher was going to stay with her Aunt Margaretha. The pair traveled with Hans, a Khoisan drover in van Wyk's service. This trip, like many other journeys between the Cedarberg and Cape Town made by settlers and Khoisan alike, would have gone unrecorded had Alida not given birth the next January.

9Aunt Margaretha entreated her niece to disclose the father's identity. When Alida named Willem van Wyk, Margaretha called the fiscaal (prosecutor), who investigated the case and charged van Wyk with incest.12 The case against van Wyk hinged on the sleeping arrangements during the journey Caabwaards, so the records of the subsequent investigation inadvertently reveal a great deal about the spatial geography of outlying loan farms and the family relationships that linked those farms to one another.

10The testimony also offers brief glimpses of Khoisan life within colonial frontier society. Hans, van Wyk's drover, appears only intermittently in the otherwise detailed account of this trek to Cape Town, foregrounding the issue of Khoisan mobility in the face of an increased settler presence. We can name Hans, noting his presence and his labor, but this superficial appearance only engenders more questions. How many times did he make the trip between the Olifants River and Cape Town? Whom did he know along the way?13 As a drover or herdsman, did he ever make the trip without his master? As an individual, did he ever take this journey—or others—of his own volition?

11 Genealogy Chart: Fig. 8.1. The Campher Family Although Hans' appearance is fleeting, the entwined image of the Campher and van Wyk families emerges with clarity from archived sources. Alida's paternal grandmother (and Antoinetta's mother) was a former slave, Ansela van de Caab.14 Her sister, Johanna, was born two years before her parents married.15 Cornelis Campher and Dorothea Oelofse went on to have nine children together, Alida being penultimate. She was 19 years younger than Johanna, and only three when Johanna wed Willem van Wyk.

12Willem was the third of nine children and part of a large extended family. He and Johanna did their part to help the family grow. They baptized their first child the same day they married, a predicament not unfamiliar to frontier families, for whom long distances often precluded frequent trips to the church. Johanna must have just given birth to their eighth child around the time that Willem and Alida left for Cape Town.16 The van Wyks lived modestly. In 1742 they had just two horses, 24 cattle, and 150 sheep.17 Although Johanna bore eight of Willem's children, four of them died young. (Johanna also had an illegitimate daughter, but Dorothea Esterhuijsen does not appear to have been part of the household in 1742.) The couple possessed less livestock than their neighbors and most of their family members, but they did have a loan farm, Kleinfontein, about 15 kilometers north of where the Doorn joins the Olifants, and a wagon.18

13

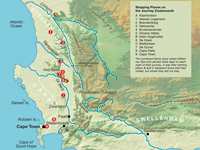

Fig. 8.2. The Journey Caabwaards

Willem van Wyk, Alida, and Hans departed these humble circumstances confident of a welcome reception in many households between Klawer Valley and Cape Town. The records from the criminal investigation of Willem van Wyk locate the travelers at specific points in the Western Cape landscape. The party spent the first night of their nine-day trip at Heeren Logement. Oud Heemraad Jacob Cloete's farm was on the coastal plain about ten kilometers south of the confluence of the Olifants and Doorn rivers, and a reasonable day's journey from Kleinfontein.19 The terrain on the east, or Doorn side, of the Olifants River is rugged and hilly south of Klawer Vally, so the most efficient route would have been to cross the Olifants soon and head across the coastal plain. The Olifants River is not deep and would have afforded many crossing points in the autumn, at the end of the dry season. Just north of the Olifants-Doorn confluence there is an obvious pass through the last ridges of the Cape Fold Belt. From that point travel southward toward Heeren Logement and onward to the Cape is over relatively flat and open terrain. In fact, the modern railway line follows a natural path in the contours from Heeren Logement to the Piketberg. That same route was probably the easiest to travel by foot and ox wagon as well.20

Fig. 8.2. The Journey Caabwaards

Willem van Wyk, Alida, and Hans departed these humble circumstances confident of a welcome reception in many households between Klawer Valley and Cape Town. The records from the criminal investigation of Willem van Wyk locate the travelers at specific points in the Western Cape landscape. The party spent the first night of their nine-day trip at Heeren Logement. Oud Heemraad Jacob Cloete's farm was on the coastal plain about ten kilometers south of the confluence of the Olifants and Doorn rivers, and a reasonable day's journey from Kleinfontein.19 The terrain on the east, or Doorn side, of the Olifants River is rugged and hilly south of Klawer Vally, so the most efficient route would have been to cross the Olifants soon and head across the coastal plain. The Olifants River is not deep and would have afforded many crossing points in the autumn, at the end of the dry season. Just north of the Olifants-Doorn confluence there is an obvious pass through the last ridges of the Cape Fold Belt. From that point travel southward toward Heeren Logement and onward to the Cape is over relatively flat and open terrain. In fact, the modern railway line follows a natural path in the contours from Heeren Logement to the Piketberg. That same route was probably the easiest to travel by foot and ox wagon as well.20

14Jacob Cloete was not at Heeren Logement when Willem and Alida arrived to spend the night there.21 Although Alida remembered knocking at the door to a house and finding it locked, it seems likely that Cloete used Heeren Logement as a grazing post while he lived on another farm a day's ride to the south. When he was proposed as a heemraad for Stellenbosch in 1739, he lived near Jan Dissels Vlei, suggesting his principal residence was Groote Zeekoe Valleij en Klein Valleij (a farm first claimed by Jan Dissel in 1729).22 Like many farmers avoiding the violent frontier war, Cloete asked to be excused from paying rent in 1739, because he "had to leave his place on account of the Hottentots."23 He must have returned to the Olifants River area after the hostilities abated, since he maintained his loan farm claims through 1761.24

15 After camping at the farm at Heeren Logement, the travelers lodged for the next two nights with farmers Alida did not know. Having spent their first night sleeping in the wagon, this hospitality was undoubtedly welcome. The court records give great attention to where Willem and Alida slept on the various nights of their journey, which makes sense in a criminal investigation seeking to establish paternity. The fiscaal did not ask where Hans slept, though. On the nights that the party camped, it is likely that Hans slept nearby. When the group was lucky enough to have shelter at a farm, Hans probably slept with the host family's slaves or other laborers.25

| Cross Reference: Read visitor Anders Sparrman's comments on traveler's sleeping arrangments. |

16

Fig. 8.3. List of Stopping Places on the Journey Caabwaards

The first farm where the travelers found shelter was near present-day Brandenburg, the second near Verloerevlei. This itinerary broke up the distance between Heeren Logement and the Piketberg into two legs of thirty kilometers and a final leg of twenty kilometers. Assuming a traveling pace of about five kilometers an hour, the approximately eighty kilometers between Heeren Logement and Kruismansrivier would have been feasible in three days.26 The fourth night of their trip the travelers stayed with Gerrit van Wyk, Willem's brother.

Fig. 8.3. List of Stopping Places on the Journey Caabwaards

The first farm where the travelers found shelter was near present-day Brandenburg, the second near Verloerevlei. This itinerary broke up the distance between Heeren Logement and the Piketberg into two legs of thirty kilometers and a final leg of twenty kilometers. Assuming a traveling pace of about five kilometers an hour, the approximately eighty kilometers between Heeren Logement and Kruismansrivier would have been feasible in three days.26 The fourth night of their trip the travelers stayed with Gerrit van Wyk, Willem's brother.

17Gerrit van Wyk had recently acquired the permit for Kruismansrivier, which lay on the east side of the Piketberg, along the most likely route from Heeren Logement to Table Bay.27 When Willem, Alida, and Hans called on him, Gerrit was 38 years old, thrice married, and the father of nine living children.28 He went on to have 19, 12 with his third wife Maria Eykoff. All of his children lived to adulthood and married, which makes the couple's 1742 opgaaf return a bit perplexing. According to the census, Gerrit and Maria were living in reduced circumstances on Kruismansrivier. It appears that the couple moved to the Piketberg region the previous year, when Gerrit took up the permit on the farm.29 Prior to 1741, the van Wyks were registered in Stellenbosch. In 1740 they reported eight slaves—six men, a woman, and a boy—eight horses, 25 head of cattle, 150 sheep, and 12 pigs; they grew wheat, rye, and barley.30 Later in that same year, van Wyk took out a lease on Kruismansrivier in partnership with Jacobus Louw Jacobusz.31 The next year's opgaaf shows a precipitous decline in the van Wyks' fortunes. By late April 1741 Gerrit, Maria, and their toddler son were living on Kruismansrivier with only one horse and 24 head of cattle. The slaves, sheep, pigs, and agricultural produce of the previous year were gone.32 Even more curious, van Wyk's seven children from his previous marriages were missing, too.

18 Genealogy Chart: Fig. 8.4. The Van Wyk Family Gerrit and his second wife, Maria Prevot, appear in the 1731 opgaaf and in Governor de la Fontaine's detailed survey of the colonists, in both cases with six minor children, including four from van Wyk's first marriage.33 De la Fontaine describes the household as indebted and "living with livestock in the veld," but the couple reported a small grain harvest that year, so they cannot have been itinerant. After Maria Prevot's death, van Wyk predictably remarried, but this wedding dramatically altered his household composition, seemingly separating him from his existing children.

19At least van Wyk's offspring were not recorded as part of Gerrit's household after he married Maria Eyckoff. Perhaps these children lived with their mothers' relatives until they married. Perhaps they lodged with other relatives or worked for neighboring families. It appears from the 1743 opgaaf that van Wyk's eldest sons Gerrit Gerritsz and Abraham were living as bachelors in the Cape district.34 His two teenaged daughters did not marry until 1748, and the next child was only ten in 1743, so she and her younger siblings certainly were not living on their own in the early 1740s. Whatever the case, they remain submerged in the archives from 1731 until Gerrit Gerritsz and Abraham surfaced in 1743 opgaaf, and the rest of the children upon their marriages.

20Alida told the fiscaal she slept at Kruismansrivier with her cousin Elisabeth Scholtz, who might have been a lodger, or another guest of the van Wyks. Alida does not explain her cousin's appearance there. Elisabeth's presence on the farm, along with Gerrit's absent children, suggests a certain fluidity among frontier households. Although several elements of the Campher and van Wyk drama imply that Alida, Johanna, Willem, and Gerrit may have lived at the margins of settler conformity, the circulation of labor and family members among Burger, Botma, and Lubbe households indicates Elisabeth's presence was unremarkable in a kin network.

^topFamily Obligations: Visits and Resources

21After four long days of travel, Willem and Alida took advantage of family connections and neighborly obligations to slow their pace. They left Kruismansrivier in Gerrit's company and journeyed an easy ten kilometers to the Groene Valleij farm, where Jacobus Gildenhuizen and his wife Anna Maria Koekemoer ran a household of some means.35 When Alida visited, Groene Valleij's abundant herds and flocks placed the Gildenhuizens well above the middling ranks of stock farmers.36 Four slaves—three men and one woman—provided labor to help with both livestock and cultivation. Their efforts the previous season yielded a bumper crop of wheat. This year, Gerrit had come to lend a hand with the plowing.37 Despite the presence of slaves—and the likelihood of undocumented Khoisan laborers—Groene Valleij nevertheless needed to call on the assistance of neighbors to get the fields prepared.

22Only proximity connects the van Wyks and the Gildenhuizens; undoubtedly Gerrit was compensated for his efforts. He planted only one muid of wheat that year, his first attempt at arable agriculture after moving to Kruismansrivier.38 With few stock of his own to tend and limited work to do in his own field, Gerrit might have been inclined to help a neighbor, especially if the return on that labor could help him augment the meager productivity of his own farm.

23Willem, Alida, and Hans did not stay to help; instead they proceeded southward the next day. En route, they called on Alida's aunt, Antoinetta Campher, probably at Klein Vogelvlei, a scant five kilometers south of Groene Valleij at the edge of the Piketberg. Antoinetta, the widow of Joachim Scholtz, had previously been married to Ary van Wyk, Willem and Gerrit's cousin. Ary claimed Klein Vogelvlei from 1724 to 1730.39 Joachim Scholtz, then married to Anna Maria Swart, took over the lease in 1730. Anna Maria, herself twice widowed before she married Scholtz, brought resources to their marriage.40 Her previous husband, Marten Mecklenburg, held 11 loan farm permits between 1706 and 1715, all of them in the Berg River area to the south of the Piketberg. Scholtz, by contrast, was fairly poor. He had no property until after his 1727 marriage to Anna Maria.41

24After his wife's death, Scholtz petitioned the Council of Policy to undertake the care and maintenance of Anna Maria's illegitimate daughter, since he could not afford it. "As the petitioner is maimed and poor, he finds it difficult to earn enough for himself and his own child."42 He managed somehow to maintain the lease on Klein Vogelvlei until his 1733 marriage to Antoinetta Campher, Ary van Wyk's widow and the previous mistress of the farm. Despite being "maimed and poor," Joachim successfully courted Antoinetta. She was clearly richer, but Joachim had the permit for Klein Vogelvlei. As the mother of ten children and a stock owner, Antoinetta obviously needed land, and Ary van Wyk did not leave them a farm.

25In her first year of widowhood, Antoinetta lived with eight of her ten children and one slave. She reported three horses, 48 head of cattle, 63 sheep, and an exceptional crop of 45 muid of wheat produced from three muid sown.43 Widower Scholtz lived with his only surviving son and kept two horses, 6 head of cattle, and 50 sheep.44 In combining their resources, Antoinetta and Joachim had a large household and reasonable, but not exceptional, resources.

26By 1740 Antoinetta found herself widowed again, but in straitened circumstances. According to the opgaaf, she lived with five of her ten children still at home but no livestock or agricultural produce.45 She was unlikely to have been as destitute as she appears on paper. We can surmise from Alida's testimony that Antoinetta continued to live on Klein Vogelvlei after Hendrik Krugel acquired the permit in 1738.46 Antoinetta's son Willem van Wyk lived close by. Her widowed daughter-in-law was also in the neighborhood and had large flocks and herds.47 Undoubtedly Antoinetta had access to resources beyond what she reported in the opgaaf.

27Although the permit for Klein Vogelvlei belonged to Hendrik Krugel in 1742, he appears to have lived on De Hoek, about ten kilometers to the south. De Hoek was the first farm he claimed; his widow subsequently assumed the title, strongly suggesting it was their principal, residential farm.48 Krugel held short-term leases on 13 other farms from the Piketberg to the Doorn River, including farms in the Roggeveld, and extending into the Karoo.49 Krugel and Maria van der Swann were prosperous and productive farmers who could afford to sublet Klein Vogelvlei or to allow the twice-widowed Antoinetta Campher to live in the hofsteede (farm house) in exchange for labor or grazing rights. In 1743 the Krugels managed abundant livestock and exceptional grain production with the labor of 12 slaves—seven men, two women, and two boys.50

28Alida's testimony hints at a labor exchange between the Krugels and the van Wyks. After visiting for an hour with Antoinetta Campher on Klein Vogelvlei, Willem and Alida traveled only as far as the farm at De Hoek that evening, logging their second consecutive short day. Alida slept that night with her sister Sophia, who was married to Christoffel van Wyk, Antoinetta's fourth child.51 Surely more than coincidence put Antoinetta's son and daughter-in-law at the Krugel's during the plowing season.52 Christoffel and Sophia had two sons and a horse, according to the 1742 opgaaf.53 They had no landed property of their own.54 The 1743 opgaaf records Christoffel and Sophia immediately after Hendrik Krugel and his wife Maria, which further supports the contention that the younger, poor couple lived in the more prosperous Krugel household.55

29Following two days of light travel leavened by visits to friends and relatives, the travelers put in another long day. Setting off southward from De Hoek, they first called at the farm of Ernst Christiaan Ehlers, only three to four kilometers from the Krugel house.56 Somewhere thereabouts they encountered Hans Jacob Brits, who traveled with them to the outskirts of the settlement at Table Bay.57 Alida does not mention Brits's company, nor does she say why they stopped at a farm at Rietfontein before proceeding onward. Late that evening the party arrived at Floris Smit's farm near Riebeeck's Casteel.58 Alida did not know Smit and his wife, Margaretha Steenkamp, nor did she recall them by name. Brits identified the couple in his statement to the fiscaal.59 Although they remembered different details, Hans Jacob's testimony was consistent with Alida's. After spending the night with the Smits at De Gunst, the van Wyk party continued southward, putting in another long day to reach the Cape Flats. They covered between forty and fifty kilometers, a journey that would have taken eight to ten hours of steady progress. According to Brits, they made camp after midnight, while Alida recalled stopping after the moon had set.60 The group would have had to rest the oxen at some point during the day, allowing them to drink and graze. If the day were warm, they would have sought shade during the hottest part of the afternoon, so a late-night arrival is plausible.

30From the Cape Flats it would have been a comfortable journey into Cape Town, perhaps less than four hours, since there were wagon roads in the vicinity. Brits parted company with Willem, Alida, and Hans at the Salt River, leaving Willem to deliver his sister-in-law to her aunt, Margaretha Oelofse.61 It took this small colonial traveling party nine days to journey from the confluence of the Olifants and Doorn rivers to the settlement at Table Bay. Their steady voyage demonstrates connections between the Cedarberg and Cape Town. The group's relationships to the people they saw along the way reveal the fibers that bound settler society: interconnected land claims, family relationships, and a sense of shared identity that included Alida, despite her slave grandmother, but erased the drover Hans from the landscape.

^topAn Almost Typical Trip

31Other than the allegations of incestuous sexual encounters when Willem van Wyk and Jacoba Alida Campher slept unchaperoned, the trip itself appears to have been unremarkable. There is no room in the format of legal proceedings for the fiscaal or the Council of Justice to interject opinion, except in the transcript of the interrogation of Willem van Wyk. In this moment where they might have made moral judgments, the colonial authorities did not question the premise behind the trip, the trip's length, or its feasibility. Long, slow travel by ox wagon was not just a necessity, it was commonplace. Such travel was important link between Cape Town and the outlying areas, especially frontier regions like the Olifants River. There was no regular postal system—as there was to the Overberg and Swellendam—so the travel of settlers themselves took on an increasing importance. The method of travel by ox wagon, the pace, the practice of lodging with farmers where possible and camping when not, are all consistent with published travel accounts of the eighteenth century.

Fig. 8.5. The Road Caabwaards

32

In a region without roads or inns, travelers would have to know the way to their destination. The course plotted by Willem van Wyk was the most logical and practical route to get from north to south. The stops as recounted by Alida, Hans Jacob Brits (for two nights), and van Wyk make sense. They are all a reasonable day's travel from one another, except for two nights the party spent near the Piketberg. There family and neighborly connections slowed the pace of travel. Alida could have arrived at her aunt a day sooner, had speed or her arrival date been the top priority.

Fig. 8.5. The Road Caabwaards

32

In a region without roads or inns, travelers would have to know the way to their destination. The course plotted by Willem van Wyk was the most logical and practical route to get from north to south. The stops as recounted by Alida, Hans Jacob Brits (for two nights), and van Wyk make sense. They are all a reasonable day's travel from one another, except for two nights the party spent near the Piketberg. There family and neighborly connections slowed the pace of travel. Alida could have arrived at her aunt a day sooner, had speed or her arrival date been the top priority.

33In a society that reckoned time by agricultural cycles rather than calendrical dates, one day more or less en route would not have been as important a consideration as making family visits and maintaining connections across great distances.62 Those links also must have provided purposeful communication, since Willem van Wyk appeared in Cape Town and was interrogated by members of the Council of Justice in March 1743, ten or eleven months after his trip with Alida.63 It is unlikely he stayed in Cape Town during that time.

34Willem and Johanna van Wyk had livestock and held permits for two outlying loan farms.64 Consequently Willem had duties which, though they may have afforded him an absence of three weeks or so during the autumn, would have required his presence in the spring for calving and lambing. Surely at least once in those intervening months, he had to move the beasts from one grazing area to another. The van Wyks had no slaves, though Willem may have been able to rely on Khoisan labor, like the drover Hans. The van Wyk sons were too young to manage on their own, the eldest surviving boy being only 3 at the time.65 Willem and Johanna Catharina were not poor but they did not have an abundance of livestock or other agricultural resources. Their own children were small and neither of their respective families was wealthy. The most reasonable assumption is that Willem returned to the Olifants River area in May or June of 1742, then made another trip to the Cape when he was questioned in March 1743.

^topThe Spatial Exercise of Colonial Authority

35Whether he was summoned to the Council of Justice and the message reached him on Kleinfontein, or whether he happened to be in Cape Town and his presence was made known to the Council, Willem van Wyk's story reveals aspects of colonial governance. Knowledge of individuals and their whereabouts, though not necessarily precise and instantaneous, was adequate for the exercise of justice. In a more celebrated case, the insurgent Estienne Barbier remained at large for 17 months in an area only about sixty kilometers from the Castle, a day's ride on horseback.66 Van Wyk, by contrast, was summoned for questioning from his farm over three hundred kilometers from the Castle, meaning he made the round trip journey at least twice in two years. The cases are admittedly different, since Barbier was harbored on farms as a fugitive. In contrast there is no evidence to suggest that van Wyk did not present himself willingly before the law. Nevertheless, both cases demonstrate the extent to which communication was more effective in the VOC colony than long, thinly populated distances and limited technology might suggest.

36In the more densely settled Drakenstein, an area with freehold grants dating to 1691, a popular bandit could find refuge for months.67 Officials searched the area and posted a notice on the church door to no avail.68 Although Barbier was a wanted criminal, people understood their own version of events. The populace kept its own counsel and kept Barbier safe from the brutal consequences of VOC justice—at least for a time.69 Four years later, in a sparsely populated and recently settled area of the frontier stretching from the Piketberg to the Olifants River, settlers maintained communication with colonial authority and with family members near Table Bay. Although the closest church door on which the government could post a notice was the Drakenstein church at Paarl—250 kilometers away—van Wyk nevertheless got the message that he was accused in a criminal case and wanted for questioning.

37Willem van Wyk's 1743 appearance in Cape Town should not be used to exaggerate the depth or effectiveness of either official or informal communication at midcentury. This example merely serves to point out that communication over long distances with limited technology and without a formal system of relays did take place. The frontier was not out of touch or beyond the reach of VOC authority centered at the Castle of Good Hope. Although the frontier was attractive to fugitives of all sorts, a notion of authority emanating from Cape Town nevertheless existed.70 This authority communicated with individuals such as van Wyk, despite his physical distance from the Castle.

38How that message arrived and why van Wyk responded remain historical uncertainties. As Ginzburg points out, historical knowledge is " . . . indirect, presumptive, and conjectural."71 The documents do not always tell us everything we want to know.

Notes

Note 1: Richard G. Klein, "The Prehistory of Stone Age Herders in the Cape Province, South Africa," Prehistoric Pastoralism in South Africa (South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 5, June 1986): 5–12; John Parkington, "Time and Place: Some Observations on Spatial and Temporal Patterning in the Later Stone Age Sequence in South Africa," South Africa Archaeological Bulletin 35 (1980), 73–83. back

Edwin N. Wilmsen, "For Trinkets Such as Beads: A Revalorization of Khoisan Labor in Colonial Southern Africa," in Sources and Methods in African History: Spoken, Written, Unearthed, 80–101, eds. Toyin Falola and Christian Jennings (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2003).

Note 2: O.F. Mentzel, A Geographical and Topographical Description of the Cape of Good Hope (1787), ed. H. J. Mandelbrote, trans. G.V. Marais and J. Hoge, (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1944). back

Note 3: Anders Sparrman, A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope Toward the Antarctic Polar Circle Round the World and to the Country of the Hottentots and the Caffres from the Year 1772–1776, 2 vols., ed. V.S. Forbes, trans. J. & I. Rudner (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1975), I:135, 175. back

Note 4: Sparrman I:176. back

Note 5: Sparrman I:146. back

Note 6: ARA: VOC 10817, Kopie-dagregister van vaandrig August Fredrik Beutler van zijn reis in het binnenland van Kaap de Goede Hoop, 1752, also describes the difficulty procuring guides. back

Note 7: Mentzel, Description of the Cape of Good Hope; Carl Peter Thunberg, Travels at the Cape of Good Hope 1772–1775, ed. V.S. Forbes (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1986). back

Note 8: For a discussion of how kin networks functioned in nineteenth-century capital accumulation and transfer, see Wayne Dooling, "Agrarian Transformation in the Western Districts of the Cape Colony, 1883–c. 1900" (PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1996). Both Leonard Guelke and P.J. van der Merwe argue convincingly that frontier households were not economically or socially isolated from the rest of the colony: Guelke, "The Early European Settlement of South Africa" (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 1974), 213–35, 258–90; van der Merwe, Trek: Studies oor die Mobiliteit van de Pioniersbevolking aan die Kaap (Bloomfontein: Nasionale Pers Beperk, 1945). For studies of the economic incorporation of the colonial frontier see S.D. Neumark, Economic Influences on the South African Frontier, 1652–1836 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957) and Pieter van Duin and Robert Ross, The Economy of the Cape Colony in the Eighteenth Century, Intercontinenta No. 7 (Leiden: Centre for the History of European Expansion, 1987). back

Note 9: Karel Schoeman, This Life, trans. Elsa Silke (Cape Town: Human and Rousseau, 2005), 30. back

Note 10: ARA: VOC 4152, OBP, 1742 opgaaf. Van Wyk did not report any grain sowed or harvested. back

Note 11: Plowing and sowing season was in April and May. Mentzel, 158; Thunberg, 136. back

Note 12: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, 1743–44, vol. 2. Testimony in the case against Willem van Wyk, 1743, ff. 928–43. I explore the ways this case illuminates sexuality and colonial morality in "Sex, Religion, and Other Cultural Exigencies in the Early-Modern Atlantic," paper presented at the Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Scripps College, Claremont, 2–5 June 2005. back

Note 13: Given the numerous examples of connections among slaves and servants provided in court testimony regarding fugitives, it is highly likely that Hans had connections of his own at the various farms where Willem and Jacoba Alida called on their trip. back

Note 14: Heese, Groepe sonder Grense (Robertson trans), 34; dv&P, 1981, 132. back

Note 15: The arrival of an onegte voorkind, or an illegitimate child, was not an irredeemable social stigma for either parent. See Gerald Groenewald, "Parents, Children and Illegitimacy in Dutch Colonial Cape Town, c. 1652–1795," paper presented to the 'Company, Castle and Control' research group meeting, 2006, University of Cape Town, 4, 21. back

Note 16: Cornelis van Wyk was baptized on 21 Apr. 1742, dV&P, 1966, 1149. back

Note 17: ARA: VOC 4152, OBP, 1742 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 16. back

Note 18: CA: RLR 38:156, 14 Nov. 1735, Willem van Wyk Willemsz permit for Kleinfontein, aan de Olifants Rivier, 1735–56. back

Note 19: CA: RLR 38:100, Heeren Logement, aan de Olifants Rivier, to Jacob Cloete, 4 July 1732–22 Oct. 1761 (per L Guelke data). back

Note 20: The Heeren Logement cave sheltered Governor Simon van der Stel and his traveling party in 1685. The cave was a frequent traveler's waypoint; subsequent visitors carved their names onto the rock wall, creating a tourist site visited since the early 1700s. For more on the site as a tourist attraction, see van Rooyen and Steyn, 23. back

Note 21: Jacob was Elsie Cloete's nephew, so he was kin to the van der Merwes (first cousin to Schalk, Marietjie, and their siblings), though not related to the Camphers and van Wyks. back

Note 22: Leibbrandt, Précis, I: 244i. In addition to Heeren Logement, Cloete claimed another parcel in the region: CA: RLR 9:318, Groote Zeekoe Valleij, over de Olifants Rivier, to Jacob Cloete 5 July 1731–1 Dec. 1744. Dissel claimed two farms in the area, Groote Zeekoe Valleij and Renoster Hoek. Renoster Hoek aan de Piquetberg: CA: RLR 6:85, 15 July 1726–16 Aug. 1728. CA: RLR 8:30, 19 Aug. 1729–21 Feb. 1731. CA: RLR 9:25, 18 Sept. 1731–31 Oct. 1732. Groote Zeekoe Valleij over de Olifants Rivier: CA: RLR 7:54, 14 Apr. 1728–14 Apr. 1729. CA: RLR 8:264, 6 May 1729–6 May, 1731. CA: RLR 9:205, 2 June 1731–5 July 1732. (All per L. Guelke data.) back

Note 23: Leibbrandt, Précis, I: 244l. back

Note 24: CA: RLR 38:100, Groote Zeekoe Valleij, over de Olifants Rivier, to Jacob Cloete 5 July 1731–22 Oct. 1761. This permit duplicates the years 1731–44 covered by RLR 9:318 and extends the permit until 1761. back

Note 25: In this case, the inquisitor/fiscaal failed in his role as an anthropologist of Khoisan actions, since his attention was focused solely on the activities of Willem and Jacoba Alida. Carlo Ginzburg, "The Inquisitor as Anthropologist," in Clues, Myths and the Historical Method, trans. John and Anne C. Tedeschi (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 156–64. back

Note 26: Guelke reckons a walking pace of about 6 km per hour when figuring the size of loan farms. "Land Tenure and Settlement at the Cape 1652–1812," History of Surveying and Land Tenure in South Africa, Collected Papers, Vol. 1., ed. C.G.C. Martin and K.J. Friedlaender (Rondebosch, University of Cape Town Department of Surveying, 1984), 21. Burchell's calculations work out to be 4.7 km/hour, based on traveling 15.25 miles in 5.25 hours, William J. Burchell, Selections from Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, ed. H. Clement Notcutt (London: Oxford University Press, 1935), 115. The notes to Sparrman's text report the average speed of an ox wagon between 4 and 5.5 km per hour, slowing to 2–3 km per hour in the mountains or crossing rivers, Sparrman 145, n71. Traveling time in a day could be anywhere between 5 and 15 hours, depending on the weather and the terrain. John Barrow, An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, (London: T. Caldwell Jr. and W. Davies, 1801), 55. See also Sparrman 146, n74. back

Note 27: CA: RLR 10:132, 21 Nov. 1741 (through 1756 per L. Guelke's RLR data). back

Note 28: dv&P, 1966, 1153–54. back

Note 29: ARA: VOC 4147, OBP, 1741 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 10. back

Note 30: ARA: VOC 4143, OBP, 1740 opgaaf, Stellenbosch p. 4. back

Note 31: CA: RLR 10:96, 27 Oct. 1740. back

Note 32: ARA: VOC 4147, OBP, 1741 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 10. back

Note 33: Leonard Guelke, Robert C.-H. Shell and Anthony Whyte, compilers. "The de la Fontaine Report," (New Haven: Opgaaf Project, 1990). back

Note 34: ARA VOC 4156, OPB, opgaaf 1741, Cape, p. 1 back

Note 35: CA: RLR 10:94, Groene Valleij to Jacobus Gildenhuizen, 18 Oct. 1740 (through 1764 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 36: ARA: VOC 4152, OBP, 1742 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 14: 20 horses, 70 cattle, 300 sheep; 10 muid of wheat planted, 100 muid harvested. back

Note 37: ARA: VOC 4156, OBP, 1743-1744, Vol. 2. Criminal inquiry against farmer Willem van Wyk, 1743. Testimony of Jacoba Alida Campher, f. 938, 16 Mar. 1743. back

Note 38: ARA: VOC 4152, OPB, 1742 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 14. back

Note 39: CA: RLR 5:130, 18 May 1724 & CA: RLR 8:153, 1 Dec. 1729 (through 1730 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 40: dV&P, 1966: 856. back

Note 41: CA: RLR 9:90, Klein Vogel Valleij aan de Piquetberg to Jochem Scholtz, 20 Nov. 1730–7 Jan. 1738 (per L. Guelke data). back

Note 42: Leibbrandt, Précis: 1053c, 26 June 1732. back

Note 43: ARA: VOC 4118, OBP, 1732 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 9. back

Note 44: ARA: VOC 4121, OBP, 1733 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 7. back

Note 45: ARA: VOC 4143, OBP, 1740 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 10. back

Note 46: CA: RLR 10:8, 31 Dec. 1738 (through 1791 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 47: ARA: VOC 4143, OBP, 1740 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 10. Willem possessed a horse and 30 cattle. Widow van Wyk had 12 horses, 30 cattle, and 500 sheep. back

Note 48: CA: RLR 9:152, 1 Mar. 1731 (through 1750 per L. Guelke data). CA: RLR 38: 53, 1 Mar. 1731 recapitulates the original lease, then transfers it to Krugel's widow (through 1792 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 49: Krugel's farms included CA: RLR 9: 15, [unnamed farm, probably Klein Vogel Valleij] aan dese hoek aan de Piquetberg, 1 Mar. 1731 to 21 May 1750. CA: RLR 38: 53, [unnamed farm, probably Klein Vogel Valleij] aan dese hoek aan de Piquetberg, to the Widow Hendrik Krugel, 1 Mar. 1731 to 21 Nov. 1792. CA: RLR 11:156, Elandsdrift, in het Karroo, 31 Apr. 1747 to 24 Apr. 1748. CA: RLR 15:128, Blinde Fonteijn, aan de Piquetberg, 1 Feb. 1759 to 29 Dec. 1759. CA: RLR 16:94, De Grendel, aan de Roggeveld, 8 Dec. 1760 to 24 Dec. 1761. CA: RLR 16:181, De Vondeling, aan de Hantam, 24 Sept. 1761 to 18 Sept. 1762. CA: RLR 17:72, Kleijn Riet Rivier, op de Roggeveld, 10 May 1762 to 9 May 1765. CA: RLR 17:120, Modder Fonteijn, over de Kleijn Riet Rivier, 13 Oct. 1762 to 29 Mar. 1769. CA: RLR 18: 65, Matijes Fonteijn, in 't Romst Veldt, 3 Dec. 1763 to 29 Sept. 1769. CA: RLR 18: 269, Ratel Fonteijn, aan 't Roggeveld, 18 Mar. 1765 to 29 Sept. 1769. back

Note 50: ARA: VOC 4156, OBP 1743 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 17: 6 horses, 56 cattle, 350 sheep; 7 muid of wheat planted, 140 muid harvested, about twice the average grain production. back

Note 51: dv&P, 1966: 1149. dV&P, 1981: 132. back

Note 52: In addition to being Antoinetta's daughter-in-law, Sophia Campher was also Antoinetta's niece. Consequently her husband Christoffel was also her first cousin. back

Note 53: ARA: VOC 4152, OPB 1742 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 3. back

Note 54: Christoffel van Wyk first appears in the loan farm records in 1746. CA: RLR 11:105, 28 Mar. 1746, for the farm Bokjesfontein in the Koude Bokkeveld. back

Note 55: ARA: VOC 4156, OPB 1743 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 17. back

Note 56: CA: RLR 9:160, Rietfontein, om die hoek van de Piquetberg over de Bergrivier, 17 Mar. 1731 (through 1763 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 57: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, 1743–44, Vol. 2. Criminal inquiry against farmer Willem van Wyk, 1743. Testimony of Hans Jacob Brits, folio 940, 1 Apr. 1743. back

Note 58: CA: RLR 10:90, De Gunst, 5 Oct. 1740 (through 1756 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 59: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, van Wyk inquiry, Brits statement, f. 940, 1 Apr. 1743. back

Note 60: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, van Wyk inquiry, Brits statement, f. 940, 1 Apr. 1743; Campher statement, f. 938, 16 Mar. 1743. back

Note 61: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, van Wyk inquiry, Brits statement, f. 940, 1 Apr. 1743. back

Note 62: On the social reckoning of time, see Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, La Clepsydre (Paris: Albin Michel, 2000). back

Note 63: ARA: VOC 4158, OBP, van Wyk interrogation, f. 943, 13 Apr. 1743. back

Note 64: ARA: VOC 4152, OBP 1742 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 16. ARA: VOC 4146, OBP 1743 opgaaf, Drakenstein p. 17. CA: RLR 38:156, Kleinfontein, aan de Olifants Rivier, 14 Nov.1735–15 Apr. 1756. CA: RLR 10: 139, 25 Jan. 1742 Vleermuijs, aan de Bergrivier (through 1745 per L. Guelke data). back

Note 65: dV&P,1966: 1149. back

Note 66: Nigel Penn, "Estienne Barbier: An Eighteenth Century Cape Social Bandit," in Rogues, Rebels and Runaways: Eighteenth-Century Cape Characters (Cape Town: David Philip, 1999), 101–130. back

Note 67: L. Guelke, The Southwestern Cape Colony 1657–1750, Freehold Land Grants. Map, no scale (Department of Geography Publication Series, Occasional Paper No. 5. University of Waterloo, 1987). back

Note 68: The Drakenstein gemeente of the Dutch Reformed Church was established at Paarl in 1691. back

Note 69: Barbier was tortured and executed on 14 Nov. 1739. Penn, "Estienne Barbier," 126. back

Note 70: For a detailed discussion of fugitives, see Nigel Penn, Rogues, Rebels and Runaways: Eighteenth-Century Cape Characters (Cape Town: David Phillip, 1999). back

Note 71: "Clues, Roots of an Evidential Paradigm," 106. back