Introduction

1Until 1800 China was arguably the center of the enormous region of East Asia. While deserts, mountains, jungles, and seas, from northwest and southwest to the south, seemed to pose daunting challenges for even the most intrepid traveler, the discoveries of the Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road have challenged the notion that the geographic hurdles left China isolated. While contributing a great deal to the understanding of ancient East-West exchanges, studies of the above two silk routes have overshadowed the third route, the so-called Southwest Silk Road connecting China, mainland Southeast Asia, India, and beyond.1 Studies of this third, relatively unknown route shed new light on the economic and military transactions and histories and cultures that developed in this part of the frontier.

2The earliest textual source identifying the Silk Road comes from Zhang Qian's exploration (138 BCE–126 BCE) of the Western Region (xiyu), which is recorded by Sima Qian in Shi Ji. But Zhang Qian's report indeed alludes to another Silk Road that connects Southwest China with India, when he found Sichuan cloth (shubu) and bamboo cane (qiongzhu) in Daxia (Bactria). Chinese historical writings prior to the Tang Dynasty (618–907), fragmentary and obscure as they are, also refer mysteriously to exchanges between China and Southeast Asia, even when nobody had reportedly completed the journey. At the turn of the twentieth century, sinologists such as Paul Pelliot devoted a great deal of energy to this matter of the passage.

3It was during World War II that Chinese scholars began further exploration. The year 1941 saw two articles on this route by Fang Guoyu and Gu Chunfan, the former written in Chinese and the latter in English.2 Seven years later, the first monograph by Xia Guangnan was published.3 From then until the 1980s, the study of this route stagnated, occasionally occupying only a tiny space in books on ancient Indian or Chinese civilization. Joseph Needham noticed this road, but his conclusion was based on the acceptance of Chinese texts.4 Scholars of India or South Asia at times mentioned the early trade between China and India via Burma. D. P. Singhal in his India and World Civilization, for instance, mentioned both overland routes through Nepal and Tibet to China, and through Assam and Upper Burma to Yunnan.5 Yu Yingshi's study on the trade of Han China did present a refined argument of the existence of the route. Nevertheless, limited by the nature of his study and by the lack of more recent archaeological discoveries, the whole picture remained incomplete.6

4Since the 1980s, scholars in China have spent tremendous efforts on this previously underestimated or neglected road. Dozens of books and articles have been counted, but many problems remain unsolved.7 Despite the abundance of Chinese sources, few could locate routes in non-Chinese regions such as Burma and Assam. What was the volume of trade? Little accurate information exists. When did the route begin to take shape? Many conflicting opinions have been generated. Even an agreement on the name of the road has not yet been reached. Some use Xi'nan Sichou Zhilu (Southwest Silk Road) or Nanfang Sichou Zhilu (South Silk Road), while others prefer the more descriptive Nanfang Lushang Zhilu (southern overland route) or Dianmianyin Gudao (ancient roads connecting Yunnan, Burma, and India). Some employ the traditional name, Shuyandu Dao (road between Sichuan and India), and others Shubu Zhilu (the road of Shu cloth), and still others do not give a specific name. I use Southwest Silk Road (SSR) to distinguish it from the North Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road.8

5While Chinese scholars have furthered this study, their weaknesses have been as outstanding as their achievements. Many works were case studies that provided details but failed to draw a comprehensive picture. A few macrostudies, however, were based on Chinese sources—mainly Han texts—and could not escape from the accusation of Sino-centricism.9 Sun Laichen, in his innovative work on overland exchanges of military technology between Southeast Asia and Ming China, criticizes previous scholarship for its lack of breadth and depth:

First, they lack breadth as they fail to treat the Sino-Southeast Asian overland interactions as a whole. Second, they lack depth because they are, by and large, descriptive rather than analytical. Third, the sources materials utilized in most of these works are largely Chinese, while Southeast Asian sources are ignored. Thus the perspective adopted is usually 'looking down south' from China and is inevitably Sinocentric.10

I would like to further this critique. Previous studies indeed lack a global view and thus downplay the global significance of the Southwest Silk Road. A global perspective of the SSR will give rise to many questions, such as: What kind of relationship had existed among the three Silk Roads? How did they function together temporally and spatially? Did they become a network linked so closely that they brought the Eurasian supercontinent into a world system? If so, when and how? If not, why not? Janice Stargardt's study on medieval Burma and Sun Laichen's research have established excellent cases in terms of interactions between the overland route and the Maritime Silk Road, each with their own specific time frames.11 I cannot help questioning those early times, and thinking about the triangular interactions among the three roads.

6This chapter explores the significance of Yunnan in Eurasian communications by focusing on the Southwest Silk Road. I intend to supplement Chinese scholarship with non-Chinese resources to draw a more comprehensive picture of the SSR. First, I will present geographic and historical maps of the road, which is expected to fill in the gap of the pre–mid-nineteenth-century international trade that is less known to some scholars.12 Furthermore, I argue that this road, while having a great influence on shaping discussed regions, combined with the other two Silk Roads, provided a systematic trade network within which the three roads functioned in a complementary fashion. This chapter to some extent adds new dimensions to our existing understanding of East-West communications as I attempt to demonstrate Yunnan's many connections with neighboring peoples as well as its significance in world history.

Historical Yunnan: Crossroad of China, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Tibet

7Yunnan encompasses a wide variety of natural conditions, characterized by mountains, rivers, gorges, plateaus, valleys, basins, forests, grasslands, and lakes. The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau is the southern extension of the Tibetan Plateau, "the roof of the world." Principal mountains in Yunnan converge in northwest and from there they fan out southward and southwestward. Although diverse and harsh, Yunnan topography creates favorable and special environmental factors to build a cornerstone for its civilized societies. Among mountains and rivers are hundreds of small fertile basins and valleys that are called bazi. Their size varies from a couple of square kilometers to several hundred square kilometers. Held by mountains and in many cases nurtured by rivers, they are endowed with flat and fertile soils, thanks to the alluvial accumulation from rivers and rains. Even though they only constitute six percent of Yunnan territory, bazi are the key to its economy and culture.

8The bazi served as the base for an agricultural economy. The Dian Lake (dianchi) region and the Erhai Region are two of the largest bazi and have cultivated the most developed agriculture. It is in such ecological conditions that the two large modern-day cities, Dali and Kunming, have developed into urban centers of Yunnan. Furthermore, bazi facilitated connections and interactions among local peoples. Relatively short distances between those bazi made transportation and commercial activities plausible. Indeed, bazi functioned as inns for merchants, providing food and housing. Bazi were also providers of commercial goods, and consumers of foreign products. If we examine maps carefully, we find that cross-regional trade routes are chained with strings of bazi. Finally, bazi in Yunnan differ by altitude, landscape, and climate, which to a certain extent accounts for the diversity of local ethnic groups. In a word, bazi symbolize the dynamic and diverse Yunnan society.

9Rivers in Yunnan are of great interest. When we examine mainland Southeast Asia, we find that its major rivers (the Mekong, Red [or Hong], Salween, and Irrawaddy rivers) nurturing fertile lands all originated on the Tibet Plateau and passed through Yunnan. If we broaden our view, other major rivers such as the Yangzi, the Pearl (zhu), and the Brahmaputra share the same origin, either passing through the Yunnan Plateau or winding around its edges. Although most rivers in Yunnan are not navigable,13 and overland roads were so crucial for communication with neighbors, Charles Higham points out that these rivers "have historically provided passages for the movement of people, goods, and ideas."14

10Higham's conclusion is based on many archaeological and anthropological findings. Paleolithic and Neolithic discoveries reveal that Yunnan began to cultivate its own cultures during its interactions with neighboring areas. Scholars of China have used and, indeed, abused, archaeological findings in Yunnan to reconstruct Chinese national history. They have used hominid fossils unearthed in Yunnan to suggest the "likelihood that the Asian continent constitutes a locus for the origin of man."15 Some of them believe that the Homo erectus yuanmouensis found in Yuanmou County (Yunnan) is dated at approximately 1.7 million years,16 and were thus the earliest human beings in the land later called China. As archaeology has been a source for nationalist expression in present-day China, these scholars have come to conclude that the "Chinese of the recent day are the descendants of the region's Paleolithic inhabitants."17 This Sinocentric claim to Yunnan's archeological riches suggests the extent to which China's sense of heritage and national pride comes from Yunnan.

11Due to its geographic location, however, Yunnan has had closer ethnic and cultural associations with Southeast Asia. Ling Chunsheng has listed fifty common cultural features among Southeast Asian peoples, such as a patronymic system (fuzi lianming zhi), secondary burial/bone-cleaning burial (xiguzang), cliff burial (yazang), pile building (ganlan), and tattoos (wenshen). These customs have been found from the Pacific to Madagascar.18 For example, bronze drums have been found in Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Yunnan, although arguments about the origin and routes of diffusion continue. All of these probably resulted from prehistorical migrations of which scholars know very little.19 Considering these facts, more and more scholars tend to put ancient Yunnan into the category of Southeast Asia rather than East Asia.20 So, what was the role of Yunnan in the origin and development of Southeast Asian civilization?

12As a major intersection of Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Central Asia, Yunnan witnessed and participated in the early migrations in the region. Some peoples in Yunnan today are the descendents of the Di and Qiang who lived in Northwest China and later moved southward. Fei Xiaotong and other Chinese ethnologists thought highly of the corridor along the Tibetan plateau that connected Central Asia and Northwest China with Southwest China and mainland Southeast Asia. They named it the Ethnic Corridor (minzu zoulang) and argued that a full understanding of early migration through this pass would shed light on many myths of ethnicity, language, and ritual around Yunnan.21 The influence of the Di and Qiang nomadic culture was evident in Neolithic relics in Yunnan, revealing the close relationship among Yunnan, Tibet, and Central Asia.22

13But northern influence did not stop in Yunnan. Tong Enzheng points out that many cultural features in Southeast Asia might have come from Sichuan, having passed through Yunnan.23 For example, the bronze culture in Sanxingdui (Sichuan) came about before the Dong Son bronze culture that Vietnamese scholars claim had an effect on South China.24 Higham has paralleled ancient civilizations represented by the Sanxingdui and the Yin ruins and concludes that in the middle of the second millennium BCE these communities "were already displaying a mastery of bronze casting which was unsurpassed in the ancient world."25 Instead of claiming its local origins, he favors the possibility that "the Southeast Asian tradition of copper-based metallurgy was initially stimulated by the spread of ideas and goods down the very rivers which introduced the rice farming groups a millennium or so earlier."26 Although Higham indicates Lingnan as a corridor spreading ideas and technology, I would like to contend that Yunnan was also a possible connection, partially because Yunnan held major tin resources in the late first millennium BCE.

14Yunnan also made cultural contributions to Southeast Asia. Bronze drums, for instance, seem to have spread from Yunnan into Southeast Asia, because those unearthed in Yunnan were dated earlier than their Southeast Asian counterparts.27 Constituent analysis of these materials suggests that their metal was mined in Yunnan.28 Other archaeological findings such as beads and collard disc-rings support the ancient connections between these two areas, which are symbolized by the spread of bronze drums.29

15While the intimate relationships between Yunnan and China and between Yunnan and Southeast Asia should not be underestimated, one should bear in mind that other cultural relationships are crucial to Yunnan as well. Tibet, for instance, has been interacting with Yunnan since very early times. In fact, the Tubo Empire once established a tributary relationship with the Nanzhao Kingdom, and ethnic people such as the Naxi in northwest Yunnan have been heavily influenced by Tibetan culture. Furthermore, the Indian world had great influence on Yunnan as well, directly and indirectly. The most revealing cases include Buddhist influences and the cowry monetary system that will be discussed later.

16Yunnan also possessed its own creative energy, which it contributed to its neighbors. While bronze artifacts in the Shang and Zhou dynasties in the Central Plain have impressed the world, scholars have been puzzled by the source of their bronze, since no large copper sites existed in North China. Arnold Toynbee implies that the metal was from the south, since "the nearest sources of tin and copper to the Yellow River basin are Malaya and Yunnan."30 Recent chemical analyses have partially confirmed his speculation that copper was mined and moved from Yunnan.31 Also, it seems to have been processed in Yunnan before being transported away.32 Although the bronze culture in Yunnan cannot be compared with the Yin ruins or the Sanxingdui site, Zhang Zengqi points out that both Neolithic and bronze culture in Yunnan were original, distinctive, and replete with signs of local dynamics.33

17Yunnan also maintained connections with the Baiyue (a hundred Yue) peoples in the southeast coastal areas. The Yue people lived south of the Yangzi River and spread as far as Indochina. Some inhabitants in Yunnan belonged to the Baiyue. Archeological findings have affirmed common cultural features that have been discussed by Ling Chunsheng and other scholars, which are also supported with linguistic evidence.34

18In general, Yunnan has been variously linked with neighboring cultures since prehistoric times. Nanzhao Yeshi (The wild history of Nanzhao) compiled by Ni He, a Ming scholar, records a tenacious local legend that not only suggests their intimate ties with all the neighbors but also suggests local concepts of the world.35 According to this legend, the founder of Nanzhao was a grandson of Asoka of West Tianzhu (India). He had eight brothers, among whom, the eldest was the ancestor of the sixteen states (in ancient India); the second, the ancestor of Tubo (Tibet); the third, the ancestor of the Han people (China); the fourth, the ancestor of the Eastern Barbarians (dongman, probably referring to ethnic peoples in modern Guizhou); the fifth, namely, himself, the ancestor of the Mengshezhao (later Nanzhao); the sixth, the ancestor of the Lion Kingdom (Shiziguo, referring to Ceylon); the seventh, the ancestor of Jiaozhi (North Vietnam); the eighth, the ancestor of the Baizi Kingdom (a local kingdom replaced by Nanzhao); and the ninth, the ancestor of the Baiyi (the Tai people).36 Therefore, Nanzhao saw not only local peoples such as the Baizi Kingdom, the White Barbarians, and the Eastern Barbarians but also China, Tibet, Vietnam, Ceylon, and India as fraternal states, revealing a cross-boundary worldview comprising all the above peoples. Such a concept of the world must have been based on the frequent interactions enabled by the Southwest Silk Road.

General Overview of the Southwest Silk Road

19Geographic location rendered Yunnan an intersection, destination, and site of cultural interaction. Indeed, it constituted a land bridge between China and Southeast Asia, and beyond, but, unlike the North Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road, the lack of textual and archaeological evidence challenges scholars to provide a comprehensive picture of the SSR, especially during its early period.

20It was Zhang Qian during his mission to the Western Region (138 BCE–126 BCE) who suspected the existence of the SSR. In Daxia (Bactria), Zhang Qian reported that he found Sichuanese items:

When I was in Daxia, I saw bamboo canes from Qiong and cloth made in the province of Shu. When I asked the people how they had obtained such articles, they told me, "Our merchants go to buy them in the markets of Yandu."37 Yandu lays several thousand li southeast of Daxia. Their customs are much like those of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go into battle. The kingdom is situated on a great river. We know that Daxia is located twelve thousand li southwest of China. Now if the kingdom of Yandu is situated several thousand li southeast of Daxia and obtains Shu goods, it seems that Yandu must not be very far away from Shu. Now an envoy to Daxia by way of the Qiang territory is in danger, as the Qiang people hate us; if we send them a little farther north, they will be captured by the Xiongnu. The road through Shu would be the most direct route, and without enemies.38

On hearing Zhang Qian's report, Emperor Wu dispatched four envoys to look for the route. They failed to find the route, but they did return with some knowledge about the indigenous population around Yunnan. These earliest records by Sima Qian leave us with invaluable as well as rather obscure information on the Southwest Silk Road.

21Extending beyond Southwest China, Tibet, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, the SSR included four main branches with many sub-branches. The first was from Sichuan/Yunnan, via Burma to India, called the Road of Chuan-Dian-Mian-Yin (Sichuan-Yunnan-Burma-India) or of Shu-Yandu (Sichuan-India) by the Chinese. Because of its enormous significance, scholars sometimes identify this branch as the SSR. However, other roads also contributed to the formation and function of the SSR. One connected Vietnam with Yunnan; one connected Yunnan with Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia; another was from Yunnan, sometimes via Sichuan, to Tibet and India. Because the main articles traded along this road were tea and horses, it was named Dianzang Chama Gudao (ancient road of tea and horses between Yunnan and Tibet).39

22Due to its historical and spatial complexity, a concise overview of these sections of the SSR is necessary for providing an overall idea of the nature of these various routes.

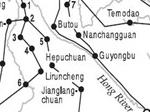

23The Sichuan-Yunnan-Burma-India Road was a major section of the SSR. It started from Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan and a symbol of the developed Shu culture that was no less significant than the Shang culture. Guanghan, a city less than one hundred kilometers from Chengdu, was the site of the well-known Sanxingdui relics that had cultivated a sophisticated bronze culture, which might have exerted great influence on Southeast Asia.40 From Chengdu through Kunming to Dali, the latter two being major commercial and cultural centers of Yunnan, there were two roads. The northern one passed the following cities: Chengdu–Linqiong (Qionglai)–Lingguan (Lushan)–Zuodu (Hanyuan)–Qiongdu (Xichang)–Qingling (Dayao, entering Yunnan)–Dabonong (Xiangyun)–Yeyu (Dali). Because the Ling Pass (Lingguan) had to be used, the northern route was called the Road of Lingguan (Lingguan Dao). The southern one went through the following cities: Chengdu–Yibin–Zhuti (Zhaotong)–Wei County (Qujing)–Dian (Kunming)–Anning–Chuxiong–Yeyu (Dali). So the two roads joined in Dali connecting the Road of Bonan (Bonan Dao), so called because it crossed the Bonan Mountain. The Road of Bonan passed through Yongchang and Tengyue to Burma and India.

24The second branch of the SSR was from Yunnan to Vietnam.41 The Hong River linked Yunnan and northern Vietnam, which accounted for some common features of bronze culture found in Yunnan and Vietnam. The route actually utilized part of the Yuan River (Hong River). It started from Miling of Jiaozhi, via Jinsang and Fengu to Dali, where it connected to the Bonan Road.42 That is why Jia Dan (730–805) of the Tang Dynasty named it Annan Tong Tianzhu Dao (the route connecting Annam and India).

25The third section connected Yunnan with Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia. Indeed southern Yunnan, Upper Burma, and Laos, cannot be divided either geographically, culturally, or ethnically. Though we lack early Chinese documents, tribute missions of small states in mainland Southeast Asia were by no means rare after the Tang. Since these routes can be seen as extensions of the Chuan-Dian-Burma-India road, I would discuss them together.

26The above three sections of the SSR are what Sun Laichen calls the "Sino-Southeast Asian overland interactions," which constituted half of the Sino-Southeast Asian communications. Obviously Yunnan functioned as a nucleus of these overland interactions. Before we turn to the connection between Yunnan and Tibet, let us first examine Chinese sources of the Tang period that illustrate the dynamics of the three southward routes crisscrossing Yunnan.

27Xuanzang (mid-seventh century) and Yijing (late seventh century), the two famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, both mentioned the route between India and Sichuan in some detail. Their records of miles and days were fairly close, which revealed that people of that time were familiar with the route.43 Fan Chuo, a military official who served in Tang China's Annam Protectorate (Annan Duhufu), recorded these roads in his Man Shu (Records of the barbarians, compiled c. 863) too.44 But all their contributions were surpassed by the details provided by Jia Dan.

28Jia Dan was a prime minister (zaixiang) of the Tang court, who in 801 presented the emperor with books that documented Sino-foreign communications. Although his books are currently missing, Xin Tang Shu (New history of the Tang Dynasty), edited in the tenth century, fortunately kept a record of the seven routes he discerned that linked China with the "barbarians" of four directions. The sixth linked Annam with India (Tianzhu). This route started from Tonkin, via Yunnan, through Prome, to Magahda.45 According to Jia Dan's records, there were two ways from Tonkin to Dali, one taking the river, the other overland. After arriving at Dali, the routes joined together, and extended to Burma and India. From Yunnan to India, again there were two routes: the southern one from Dali to Yongchang, through the Pyu Kingdom, Prome, the Arakan Range, Kamarupa, and arriving in India; the western one crossing the Irrawaddy and the Mogaung rivers, the Chindwin River to India, and beyond. This western route was about 3,200 li, compared with 5,600 li of the southern route. The southern route seemed too roundabout, but it was important, because it not only linked Yunnan and Burma but also connected the Maritime Silk Road with the SSR, which explained why merchants bothered to take this longer and winding way.46 Because all the above sources were recorded by the Chinese, and many of them indeed were cited from official and pro-official histories, it was no wonder that scholars could have such a relatively clear map of the SSR within the boundaries imagined by the Chinese. Indeed, one of the shortcomings of present research concerns the section connecting Burma, Assam, and the Indian states.

29Mountainous regions characterize areas from Burma to Assam and westward. These parallel south-north ranges are natural communication barriers. Fortunately, many passes exist, presumably fully utilized by peoples on both sides, however local peoples left us without any early documents. Modern and contemporary descriptions, nonetheless, may help us trace the routes of earlier times.

30When examining how bullion was shipped from Yunnan and Upper Burma into Bengal between 1200 and 1500, John Deyell illustrated the intertwined network of three overland routes from Yongchang, through Upper Burma westward to Bengal.

The first went from Yung Chang to Momien, crossed the Irrawaddy to Mogaung, went north through the Hukong Valley, across passes in the Patkai Range, to the upper Brahmaputra Valley. This was the eastern frontier of Kamarupa. The second route followed the Shweli River, crossing the Irrawaddy at Tagaung, followed the Chindin River north and crossed via the Imole pass to Manipur. This was the eastern approach to Bangala via Tripura. The third route embarked on the Irrawaddy at Tagaung, Ava or Pagan, and then passed from Prome over the Arakan Range to Arakan. A variation of this went directly from Pagan to Arakan via the Aeng pass. This gave access to either a land route northwards to Chatisgaon, or embarkation on the coastal trading boats to Bengal.47

31Nisar Ahmad, when discussing the Assam-Bengal trade of the medieval ages, also detailed the trade routes between the two areas. Three routes lead from Assam to Bengal: one by water and the other two by land. The Brahmaputra River was an excellent waterway for the movement of vessels. Of the two land routes, one was from Tezpur (Darang district of Assam) to Lakhnauti (the capital of Bengal Sultans) through the districts of Kamrupa and Goalpara, in the north of Brahmaputra; the second route was in the south of the Brahmaputra River. When crossing the river, it joined the first path. The second path seems to be favored by merchants who were interested in sea-trade, since it connected with the river ports of Bengal. Moreover, Lakhnauti had the advantage of a line of connection with Tibet via Kamrupa. Likewise, there also was a route from Kashmir to China (Yunnan) via Koh-i-kara-chal (Kumaon Mountains), Patkai Hills, and the upper districts of Burma, which was joined by a passage from Lakhnauti. Furthermore, Nisar points out that some portions of the three routes (Lakhnauti-Tezpur, Lakhnauti-Tibet and Lakhnauti-China) were probably common.48 Though both scholars hypothesize about routes of the early medieval ages, ancient routes should have been similar, due to local topography.

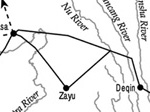

32The last section of the SSR was between Yunnan and Tibet. The Yunnan-Guizhou plateau is indeed an extension of Tibetan Plateau so that northwestern Yunnan naturally connects to Tibet. During the Ming Dynasty, Yunnan exported tea to Tibet, which began the climax of this route. Tea started from Puer, via Dali, Lijiang, Zhongdian, Zayu, Bomi, to Lhasa, and from Lhasa to Nepal and India. However, because Sichuan also neighbored Tibet, the Yunnan tea could pass through Sichuan to Tibet. Likewise, the Sichuan tea could be shipped through Yunnan, too. These routes are exactly what Deyell notices: "A separate apparently well-traveled and renowned route led from the region of the Upper Yangtse-Mekong-Shalween rivers through Tibet. Passes led through Bhutan and Nepal into Kamarupa and Hindustan respectively."49

33Known as the Tea Horse Route, the Yunnan-Tibet connection started much earlier than in the eighth century, when Tibetan people began to drink tea. However, since Yunnan bordered Tibet, Burma, and India, it could take the southward road through Burma, India, and then to Tibet. Fan Chuo also noticed this southern route.50 Roundabout as it was, the route had often been used before the Tang period, because it converged into the Yunnan-Burma-India route. Still, this way was much longer. Communications between India and Yunnan had quite often taken the northwestern branch since the eighth century, which was a result of the close relationship between Yunnan and Tibet. In fact, the Tibetan Tubo Empire once controlled northwestern Yunnan, where many local states accepted Tibetan suzerainty in the seventh and eighth century.

34Above is a very short overview of the Southwest Silk Road. Despite the introduction of maps, it should not be forgotten that the four sections emerged at different times. The sections functioned variously, and their sub-branches changed courses historically. In the following parts of the chapter, I will examine the four sections one by one to reveal the details of the historical changes that took place.

The Genesis of the Yunnan-Burma-India Road

Tracing the Origins of Trade Materials

35Scholars consider the Yunnan-Burma-India Road (dianmianyin dao) the main path of the Southwest Silk Road and the other three sections its branches. Because of its significance, scholars often focus their discussions on this main path, examining it in order to discover the origins of the SSR as a whole.

36When Zhang Qian saw cloth and bamboo canes from Sichuan in Bactria of the late second century BCE, he suspected a route between Southwest China and India. So he reported on this possibility to Emperor Wu,51 who then dispatched his envoys to explore the way to India. All of them failed, with one having been stopped by the Kunming people in Yunnan. Many scholars of China such as Fang Guoyu accepted what Zhang Qian reported. They believed that the road was in use as late as the second century BCE. Could the date have been pushed back earlier? The majority of scholars in China support the argument that the road emerged as early as the fourth century BCE. One piece of evidence they cited was what Ji Xianlin, a most famous scholar of Sino-Indian cultural relationships, discussed the word cinapattas in Arthasastra, a Sanskrit work of around the fourth century BCE. Cinapatta was translated by Ji into "bunches of Chinese silk," implying that Chinese silk was known to Indians at that time.52 However, how did Chinese silk make its way to India? Ji listed all the routes between India and China, including the three Silk Roads and the Nepal-Tibet-China route. It is possible that the silk went through the SSR, but considering the threat posed to silk by its jungles, I doubt this speculation.

37Archaeological findings in Sichuan and Yunnan may shed some light on this issue. Since the 1950s tens of thousands of cowries in Yunnan have been found in tombs dating back to between the Warring State period (475 BCE–221 BCE) and the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). These cowries were from the Pacific and Indian oceans, especially from the Maldives. They may have been shipped to Burma first and then arrived in Yunnan in the same way, but it is more likely that they went first to Bengal by sea, and then were brought to Yunnan through overland routes, since navigation between the Maldives and Burma was harder than that between Bengal and the Maldives. If so, the route could be traced back to the mid-first millennium BCE. Could the date be earlier still? It is possible.

38Several hundred cowries have been found in the Sanxingdui relics near Chengdu, in tombs that are dated about 1100 BCE. The shells, like what was unearthed in Yunnan, belong to the Cypraeetitris, Monetaria annulus, and Monetaria moneta species and, although they may have come from the southeast coastal areas via the Yangzi River, it is more likely that they arrived via the SSR, considering again the overwhelming challenge of navigating from South China Sea or the Indian Ocean to South or Southeast China. If they did indeed follow the SSR, the spread of bronze drums suggests that the road is dated to the late second millennium BCE.53

39Other archaeological articles discovered in Yunnan may have hastened the emergence of the SSR prior to Zhang Qian's time. Xia Nai in 1974 noticed that a decorated carnelian bead (shihua rouhong shisuizhu) around the third or second century BCE in Shizhaishan (Jinning County, where the capital of the Dian Kingdom was located) was manmade. Such beads were also found in Xinjiang and Tibet. Made in India and Pakistan, they spread westward to Egypt and northward to Iran. Xia pointed out that this decorated carnelian bead either could have been imported or made locally in Yunnan.54 Later, another decorated carnelian bead was found in Lijiashan (Jiangchuan, Yunnan) and is dated around the fourth century BCE. Zhang Zengqi argues that both beads were imported on the grounds that many agates were uncovered with the beads, and if the beads were made locally, why were more, rather than just two, not unearthed?55 In another tomb in Lijiashan, a blue transparent liuli bead was found.56 It is dated in the same period as the carnelian bead. This blue bead, never seen in inland China before, was different from local products in terms of design, color, and transparency. Hence it was suspected to have been imported.57

40Amber beads found in interior China provided further evidence. It is believed that these ambers came from Yunnan, since Yongchang was recorded to produce such beads. It now appears that Yongchang was just a transit station for beads from Burma.58 Two other items found in Shizhaishan, dated around the same time as the carnelian bead, were believed to have been imported from Central and West Asia. One was a gold-and-silver belt hook inlaid with a winged tiger whose eyes were transparent yellow liuli beads (youyihucuojinyindaigou). This kind of belt ornament never appeared in China until the third century, about four hundred years later. The other was a bronze button with gold-plated sculpture (liujin fudiao tongshi kou). Standing on the sculpture were two animals that were suspected to be lions. However, lions are not indigenous to China, and the first lion was reportedly presented by Parthia in the first century. Though they were possibly transported through the Silk Road, Zhang Zengqi insisted that they moved along the SSR.59 Carnelian beads unearthed in central Thailand suggest that Zhang probably is right,60 but we still lack solid evidence.

41Indeed Zhang Qian's account is as questionable as it is invaluable, precisely because he was a sole witness. Scholars question why bamboo canes, which were cheap products, were taken several thousand miles away; South India had its own bamboo and cloth.61 Other scholars responded that shubu was indeed not cotton, but a kind of linen (ma) product, and that qiongzhu too had relatively high value.62. Xia Nai and others also contest the existence of the SSR because the hardship brought by climate and topography, as well as the heterogeneity and enmity among local tribes and states would have made the route a most difficult one to follow63As a result, these scholars either denied the existence of the SSR in Zhang Qian's time or sought alternative passages.64 One possibility was a route from Shu (Sichuan) via the Yelang Kingdom (Guizhou) to the Southern Yue (Guangdong and Guangxi), joined by the Maritime Silk Road.65 Another possibility was from Yunnan via the Hong River or the Panlong River to Jiaozhi (Vietnam), then taking the Maritime Silk Road.66 Local products from Sichuan could have taken the Sichuan-Tibet route.67 We have no reason to deny these alternatives, since the Han court seemed to have known very little about Yunnan before Zhang Qian's report.68 However, it seems that the Maritime Silk Road prior to the second century BCE was no less demanding than the SSR. And of course, the road from Yunnan to Jiaozhi was part of the SSR.

42Most scholars do not deny the existence of the SSR; they only doubt it came into existence before the mid-first millennium BCE. Indeed, many eminent scholars, including Paul Pelliot, Fang Guoyu, and Rao Zongyi, agree with Zhang Qian as well as a few early non-Chinese texts. Arthasastra, which was composed in the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (late fourth century BCE), reads, "My teacher says that, of the land-routes that which leads to the Himalayas is better than that which leads to the South. Not so, says Kautilya, for with the exception of blankets, skins, and horses, other articles of merchandise, such as conch-shells, diamonds, precious stones, pearls and gold are available in plenty in the South."69 If this source is truly of the fourth century BCE, we can postulate that trade along routes leading to the Himalayas was well-established. One of those routes leading to the Himalayas probably went through Upper Burma to Yunnan, on the grounds that blankets, skins, and horses were famous local products in Yunnan. However, Tibet was known for these products, too.

43Some Western sources seem to support the above speculation. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written by a Greek of the mid-first century, says, "After the region (Chryse) under the very north, the sea outside ending in a land called This, there is a great inland city called Thinae, from which raw silk and silk yarn and silk cloth are brought on foot through Bactria to Barygaza."70 Wilfred Schoff points out that Chryse was the Malacca Peninsula and This actually meant the Qin Empire whose capital is Thinae (Xianyang).His interpretation may be correct since many famous Malay products such as gold, tortoise-shells, and pearls are mentioned by the Greek record, and the geographical descriptions of the neighborhood are basically accurate.71 It is interesting to notice the south-centric view of the author who mentions that the Qin was located in the north, which means that he might have landed in Burma and might also have known the road led northward to China. If so, the road from coastal mainland Southeastern Asia via Upper Burma and Yunnan leading to inland China might have been utilized before, even long before, the arrival of the Greeks.72

44While some scholars turn to the emergence of shubu and qiongzhu in Bactria to suggest the west-bound migratory pattern of materials, Joseph Needham advances the Bactria alloy theory to make the same argument. In Science and Civilization in China, Needham offers a summary of his theory: "The Greek kingdoms in Bactria during the first half of the second century BCE used a cupro-nickel coinage, so far as is at present known the oldest in the world."73 Cupro-nickel, or paktong (from the Chinese term baitong, literally meaning "white copper"), had been tested by nineteenth-century scientists, and they proposed "that the nickel of the Graeco-Indian coins must have come overland somehow from China; thus initiating what came to be called the 'the Bactrian nickel theory.'"74 W. W. Tarn, in his Greeks in Bactria and India, clearly already believed that Bactrian nickel came from China.75

45Needham insists that "the ratios of the constituents in the Bactrian alloys (copper, lead, iron, nickel, and cobalt) are closely similar to those in classical Chinese paktong," and that "out of nine known Asian nickel deposits only those in China would have been likely to give the ratios found."76 Here Needham refers to Yunnan, and he is "inclined to believe" that paktong was shipped from Yunnan and passed through Xinjiang.77 Obviously, Needham forgot the route through Burma.

46Scholars opposing the Bactrian alloy theory have made comparatively weak arguments. Schuyler van R. Cammann, for example, constructs his argument by pointing out that in the third century BCE, Yongchang "was a wild and barbarous area."78 The backward and "barbarian" image of the Ailao people around Yongchang again is the result of assumed superiority of Chinese culture. After all, bronze metallurgy in Yunnan was much advanced in the middle of the first millennium BCE. Additionally, since there were no other sources of paktong at the time, where else, other than Yunnan, could it have come from?79 Schuyler Van R. Cammann highlights the alloy theory's flaw: If paktong traveled through the SSR, why were nickel alloys not found in other sites in India?80 Presently, no answer exists. Another conspicuous problem is that no paktong items earlier than the Ming period (1368–1644) have even been found in Yunnan.81

47I agree with the argument that the road came into being before the Qin-Han period, namely, before the third century BCE. Nevertheless, it is difficult to ascertain when sporadic exchanges turned into a regular trade unless supplied with further evidence, leaving the chance for future archaeological findings. Assuming the existence of the SSR at that time, we should not exaggerate the scale of trade. I can therefore appreciate Harald Bockman's cautious approach regarding Yunnan trade during the Han times (206 BCE–220 CE), concluding, "There is still too scant evidence for proclaiming it a 'Southern Silk Road,'" for there are "very few archaeological indicators" of the volumes and goods of the trade.82

Text, Tribute, and Trade: Further Evidence for the Yunnan-Burma-India Road

48Efforts of the Western Han and Eastern Han to bring Southwest China into their own territories left us many more textual documents on the trade along the Yunnan-Burma-India Road. In 122 BCE, when one Han envoy dispatched by Emperor Wu reached as far as the Dian Kingdom, Changqiang, the king of Dian, detained them. The Han envoy waited over a year, as the Kunming people blocked their way westward so that none of them were able to reach India.83 But "they did learn, however, that some 1,000 or more li to the west there was a state called Dianyue whose people rode elephants and that merchants from Shu sometimes went there with their goods on unofficial trading missions."84 It was possible that Changqiang and the Kunming people stopped the Han envoys just like the Parthia people blocked Ban Chao, an Eastern Han envoy of the first century who was expected to open direct communications with the Romans.85 Both of the Han attempts to open direct communication failed because local peoples wanted to retain their secret and monopolize one part of the highly profitable long-distance trade.

49The above documents present us with further information of the SSR, for instance, about the Dianyue state, about which scholars disagreed. Some argued that it was located in present-day Tengyue in southern Yunnan; some stated that it was Piaoyue (panyue or hanyue), an ancient state located in Burma; other insisted that it was Kamarupa in Assam.86 No matter where it was, the Shu merchants had been there and it seemed that they wanted to keep the trade a secret, which suggested that long-distance trade had already been going on.

50By the end of the first century, the Han Empire controlled most of what today is Yunnan. Many tributes to that time have been recorded: In 94 CE, Moyan, the king of Dunrenyi, located outside Yongchang Prefecture, sent a tributary envoy with rhinoceros and elephants; in 97 CE, Yongyoudiao, the king of Sham, and other barbarians, out of the frontiers, presented treasures.87 Emperor He presented Yongyoudiao with a gold seal (jinyin) and purple ribbon (zishou) and gifted other "barbarian" chiefs with silks and coins; both of these tributary missions were accompanied by interpreters. In 107 CE, the Jiaoyaozhong, with over 3,000 people out of the frontiers, subjected themselves to the Han Empire by presenting elephant tusks and oxen. In 120 CE, Yongyoudiao sent a tributary mission again that included musicians and acrobats. The latter was said to have the magical power that enabled them to spit fire, decompose their bodies, and switch heads between horse and oxen. They called themselves Haixiren (people west of the sea).88 Significantly, haixi usually refers to Rome.

51Compared to the few missions from the North Silk Road, the frequency of tribute missions (around the second century) from the southern regions is noteworthy. The astonishing contrast lies in the decades of chaos in Central Asia after the collapse of the Western Han; at the same time the contrast reveals the increasing significance of the SSR. Probably suffering from the blockades in the north, peoples in the west had to turn to alternatives, and the SSR seemed to be the shortcut. Interestingly, the author of Periplus of the Erythraean Sea might have noticed or might have taken the same route in the mid-first century, just a little earlier than the time of these tributes. If we doubt whether the SSR was open in the time of Zhang Qian, the above Chinese and Western sources together have shown that the route was prosperous at least around the mid-first century. The History of the Eastern Han Dynasty clearly states that Haixi was Daqin (haixi ji daqin ye), and that the Sham connected Daqin southwestward (shanguo xi'nan tong daqin).89 Unfortunately, India was rarely mentioned. But the Yandu people were recorded in Hua Yang Guo Zhi.90 That is why Yu Yingshi, after examining both textual and archaeological evidence, was more inclined to accept the existence of the India-Burma-Yunnan trade route in the Han time.91 He concludes that "it seems beyond doubt that the Southwestern Barbarians must have developed increasingly close economic relations with some of the natives of Burma and India and, through them, Han China also gradually but steadily came into economic intercourse with both Burma and India along this famous trade route."92

Trade and the Emergence of Cities

52Benefiting from frequent trade missions, Yongchang, the frontier city of the first century, became an important international trade center. Indeed, it was said that "Yongchang produces exotic goods" (Yonchang chu yiwu).93 Significantly, the word chu means not only "produce" but also "export," implying that the goods considered "exotic" were probably not locally produced. Both HYGZ and HHS present the list of "exotic" articles, including copper, tin, lead, gold, silver, jade, precious stones, liuli, cowries, pearls, ribbons, elephants, water buffalos, cattle, ivory, peacock, cottons, and so on.94 Diverse merchandise was brought by diverse merchants. HYGZ mentions that there "live peoples of Minpu, Jiuliao, Biaoyue, Luopu, and Yandu."95 Merchants from the west, for example, the Haixiren (people west of the sea), were also recorded in HHS.

53The prosperity and dynamics of Yongchang can be confirmed by its growing population. When the king of Ailao submitted his kingdom to the Eastern Han in 69 CE, it is recorded that the Ailao Kingdom had a population of over half a million. The Han court then set up a Yongchang Prefecture, administrating the Ailao area and six counties from the Yizhou Prefecture. One source reads, "Yonchang Prefecture [has] eight cities, 231,897 households, and 1,897,344 people."96 A frontier area, as Yongchang Prefecture was, its population ranked almost the largest among all temporary prefectures, more than that of Shu Prefecture (1,350,476), the traditional center of Southwest China.97 No other reasons than international trade accounted for the population. The above statistics may have been exaggerated; nevertheless, other sources still affirm that Yongchang was one of the most populous areas in Southwest China, and it continues to be so.98 These documents have severely challenged Bockman, who questioned the existence of trade during the Han period, and I agree with him that it is hard to justify a "Southern Silk Road," because silk was not a major trade item.

54The collapse of the Eastern Han in the early third century left a chaotic world in China for more than 300 years until the unification of the Sui Dynasty in 581. There were not too many sources of the SSR after the fourth century, with the Maritime Silk Road flourishing. One source stated that a Buddhist pilgrim around the fourth century took this route to India.99 Yijing, a Tang monk who arrived in eastern India, saw a monastery that was built by Srigupta for over twenty Chinese pilgrims from Sichuan who had traveled through Yunnan and Burma.100 Two hundred and twenty-seven monks were calculated to have traveled before the end of sixth century, including Chinese pilgrims to India and Indians to China.101 Among them, many might have taken the Sichuan-Yunnan-Burma-India Road.

55The rise of local powers in mainland Southeast Asia from the seventh century onward reflects the ongoing cross-regional trade. Six or eight kingdoms in the Dali area, including Nanzhao, emerged, and Nanzhao became the first unified kingdom around Yunnan. A number of towns flourished in the Nanzhao and Dali periods. Likewise, many regimes thrived in mainland Southeast Asia in the early medieval period (by which I mean the eighth to mid-thirteenth centuries).102 Fang Guoyu, by examining diverse Chinese sources, provides a list of kingdoms, city-states, towns, and tribes or tribal alliances that were located in mainland Southeast Asia and had contacts with Nanzhao. Besides Nanzhao and later Dali in Yunnan, this list includes the Pyu (Biao), Pagan (Pugan), Miruo, Michen, Kunlun, Bosi, Luzhenla, Shuizhenla, Canbanguo, Nüwangguo, Daqinpoluomen, Xiaoqinpoluomen, Kamarupa, and so on.103 Historian G. E. Harvey points out that "the Chinese described Burma in the ninth century as containing eighteen states and nine walled towns all of which were dependent on the Pyu. Their chief town was Prome but traditions of them survive as far north as the Kabaw valley."104 Harvey adds that

after the fall of Prome[,] its people migrated to Pagan, merged with the local tribes, and thereafter were known as the Burmese. A cluster of nineteen villages, Pagan developed into a town that became the capital of all Burma from the eleventh to the thirteenth century. The situation is good, near the confluence of the Chindwin and Irrawaddy rivers, and it was probably here that a trade route from the Shan states joined one from Yunnan on their way to Assam.105

Because of the frequent trade and tributary missions, the Chinese noticed increasing internal interactions within mainland Southeast Asia. Jia Dan, for instance, recorded a route connecting Huanzhou (central Vietnam) with Wendanguo or Luzhenla (around Laos) and Shuizhenla (around Cambodia).106

56The profit of trade facilitated the strength of Nanzhao, and the drive to control trade may have been the impetus for Nanzhao's military campaigns against other southern states. Nanzhao, according to Chinese texts, had military conflicts with the Pyu, Michenguo, Miruoguo, Shuizhenla, Luzhenla, Nüwangguo, Kunlun, and helped the Pyu defeat an attack from the Shiziguo.107 Nanzhao, probably having imposed its own tributary system on the Pyu and other Southeast Asian states, took a Pyu mission to Chang'an to pay tribute to the Tang court.108 Pyu music and instruments were presented and welcomed in the Tang court. These missions may have been the key source for updated knowledge of Southeast Asia for the Chinese. It was certainly not a coincidence that Jia Dan's books on Sino-foreign communications were presented only seven years after the establishment of the Tang-Nanzhao alliance.

57The burgeoning towns and states might have taken shape earlier; however, the fact that they were recorded by the Chinese at this time leads to two conclusions. First, the emergence of a series of towns and states were not only nurtured by the Maritime Silk Road but also by overland trade and communications. To put it simply, commerce through the interplay between the SSR and the Maritime Silk Road was the logical reason for urbanization. Second, communications around Yunnan (the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms) were so frequent that the Chinese, through direct or indirect contacts, greatly improved their knowledge of mainland Southeast Asia, as revealed in Fan Chuo's Man Shu.109

58When the Dali Kingdom was established in Yunnan, trade continued to flourish, but unfortunately, not so many records about these trade routes existed. The shortage of Chinese sources resulted from the intentional decision of the Song Dynasty (961–1279) to reduce and control communications with Dali when Song China was struggling to keep the northern neighbors from invading. Although the Song blocked trade between Sichuan and Yunnan, commercial links between Yunnan and Guangxi developed because the Song needed horses from Dali. Moreover, there was no reason to doubt the trade between Dali and Southeast Asia, considering the prosperity of the Maritime Silk Road. Some texts reflected that Dali kept close relations with states in mainland Southeast Asia. For example, in 1136, Dali and Pagan paid tributes in the Song court.110

59As discussed above, Yongchang, the extreme southern frontier city, became a major international trade center of China around the second century. The fame of Yongchang lasted many centuries, and the trade probably grew even more prosperous in the Nanzhao and Dali periods. Merchants and merchandise in Yongchang indeed were not only from southern coastal areas but also from Annam. This was noticed by Zhang Jianzhi, a Tang minister, as he insightfully stated that Yongchang communicated with Daqin to the west, and to the south, with Jiaozhi, a region that is in modern-day North Vietnam.111

The Yunnan-Vietnam Path

60The communication between Yunnan and Vietnam can be traced back a long time. The similarities between bronzes and other cultural artifacts and suggest strong historical ties between Yunnan and Vietnam. Chinese texts record that a prince of the Shu Kingdom conquered northern Vietnam in the third century BCE, when the Qin expanded into the Shu. The prince's trip from Shu to Vietnam might have passed Yunnan. Though the story was recorded quite late, some Vietnamese scholars believed it to be reliable.112 But when did the communications between Yunnan and Vietnam start?

61Paul Pelliot, in the early twentieth century, while recognizing the Chinese administration of northern Vietnam around the first century, stated that no document existed to trace communications between Yunnan and Tonkin at that time.113 Nonetheless, scholars of China have revealed the relevant passage in Shui Jing Zhu, a geographic work of the sixth century that Pelliot overlooked.114 When discussing the Yeyushui (Hong River), Shui Jing Zhu cites Ma Yuan's story. Ma Yuan was a general of the Eastern Han who put down a rebellion in Jiaozhi in 43 CE. Upon hearing of the rebellion in Yizhou (Yunnan), Ma Yuan suggested that his army move to Yunnan, giving a detailed description of his route.115 Thus, the route between Yunnan and Vietnam must also have been quite broad if Ma Yuan believed that his army could advance. Another Chinese source traced this relationship back a decade earlier. In the late Western Han, around the first century, when Wen Qi was assigned as governor of Yizhou Prefecture, Gongsun Shu occupied the Shu area and claimed independence. Gongsun asked for Wen Qi's submission but was refused. When Wen Qi heard about the founding of Eastern Han, he sent his envoy to Luoyang by way of Jiaozhi.116

62More sources of the third century have documented this Yunnan-Annam connection, thanks to the tight competition over Jiaozhi and Nanzhong between the Shu regime, based in Sichuan, and the Wu regime, based in Jiangnan (south of the Yangzi River). Liu Ba, an envoy of the Wei Kingdom from North China, was dispatched to Changsha, Lingling, and Guiyang, all south of the Yangzi River. However, the above three prefectures were taken by the Shu, and Liu could not return back. Liu Ba then went southward to Jiaozhi, from there to Yunnan, from Yunnan to Sichuan, and finally returned to North China.117 When the Shu surrendered to the Wei, the Wei then sent an army to take over Jiaozhi, which had been occupied by the Wu. Seven years later the Wu army of 300,000 soldiers took it back.118 Such frequent and heated military competition revealed the access to and significance of this connection.

63The military events signified the close communication between Yunnan and Vietnam, but the communication was no less commercial. Because of its location, Jiaozhi (now as Jiaozhou) became the major port city of the Maritime Silk Road before the Tang Dynasty, when navigation technology developed so much that ships preferred to arrive in Guangzhou.119 Docking in Jiaozhou, some merchants took the route to Yunnan. Commercial items included rhinoceros, elephants, pearls, horses, silver, copper, silks, cloths, jade, precious stones, spices, tortoise shell, and so on. Hence international trade partially explains why the Shu and the Wu both tried to control Jiaozhi.120 The prosperity of the Nanhai trade certainly yielded a positive effect on the Yunnan-Annam connection, as exotic goods in Yongchang came not only from the west but also from Jiaozhi.121

64The seventh century witnessed the rise of Nanzhao in Yunnan, but the trade between Yunnan and Vietnam, namely, Tang China's Annam Protectorate, continued. Nanzhao exchanged its horses for Vietnamese salt. A couple of skirmishes between Nanzhao and Annam resulted from the unfair trade that the governor of Annam forced on the Nanzhao merchants. The hostility, of course, had negative effects on communication, but private trade never seemed to have stopped. Indeed, because of strict Tang isolation of the Sichuan frontier passes for a period of time, and because of Tubo's control of its southeastern frontiers, the Yunnan-Vietnam communication was rather regular, which can be accounted for by Yi-mou-xun's envoy to Chang'an. Unable to tolerate Tubo's extraction, Yi-mou-xun, the king of Nanzhao, sent three envoys to Chang'an to seek an alliance with Tang China. One envoy took the way through Annam, which implied that the Yunnan-Annam connection was thought to be a regular line of communication.122

65Nonetheless, Yunnan-Annam communication declined in the late Tang after wars around Annam destroyed the trade, and the independence of Annam probably had negative repercussions for trade. In addition, Guangzhou gradually took the place of Jiaozhou in the Nanhai trade. However, trade through Guangxi prospered during the Dali-Song period, as this frontier area neighbored both the Dali Kingdom and Annam that sought to trade with the Song. Moreover, Qinzhou and Lianzhou, the two port cities of Guangxi, also attracted the sea trade.

66The Song state established over a dozen markets in Sichuan and Guangxi to trade Yunnan horses from Dali.123 While horses were the major goods, there was no lack of other articles. Silk, cloths, salt, tea, and even Confucian books and Buddhist sutras from China were exchanged for oxen, elephants, sheep, chicks, gold, silver, weapons, armor, and various herbs from Yunnan. Furthermore, Dali gained access to the sea products through these markets. Markets were set up by the Song state in Qinzhou, a major port city, and in Yongpingzhai, designed for merchants with diverse sea goods from Annam. Hence, Dali, Song, and Annam participated in a trade networks around Guangxi, namely, the Yongzhou (Nanning, Guangxi) Road.

67The Yongzhou Road was so named because Yongzhou had a major horse market. Three branches from Yunnan leading to Yongzhou through Guizhou (northern, southern, and middle), were all detailed in Zhou Qufei's Lingwai Daida of the thirteenth century.124 The northern route started from Dali through Shanshan (Kunming), ran through Luodian State (Anshun, Guizhou), and reached the Hengshanzhai Market. The middle route started from Dali through Shanshan (Kunming), went to Shicheng (Qujing), Luoping, Qi (Xingyi, Guizhou), crossing the Nanpan River, to Sicheng (Lingyun, Guangxi), and then to the Hengshanzhai Market. The southern route started from Dali, carried on through Kaiyuan, Guangnan, Aian (Boai, Guangxi), Napo, and Ande, and then came to the Hengshanzhai Market.125

68But the route, in fact, did not end either in Dali or in Yongzhou. From Dali it led to Burma and India, or northeastward to Tibet. From Yongzhou, the route went southward, either to Annam or Qinzhou, a port city in Guangxi. From Qinzhou merchants could sail to Guangzhou or other ports along the southeastern coast, or to Southeast Asia. If they took the northeastward overland routes from Yongzhou, merchants were heading for Jiangnan, the center of the Southern Song, and the richest area in the world at the time.126 The road between Yunnan and Yongzhou in the Dali/Song time became extremely important; as Zhou Qufei concluded, "The roads between China and southern barbarians, must take the way of Hengshanzhai in Yongzhou."127

The Yunnan-Tibet Path

69As stated above, the Yunnan-Tibet connection included two branches, the southern and the northwestern. The former could be seen as an extension of the Yunnan-Burma-India communication link. Fan Chuo recorded that this route first led south, crossed the Gaoligong Mountains, entered Upper Burma, and turned northwestward to Zayu, Tibet.128 Zayu, a frontier town of cross-regional network, could either reach Burma or India or Yunnan, but the direct one between Yunnan and Tibet certainly was the northwestern route that was called the Tea Horse Route.

70The Tea Horse Route was detailed in the Nanzhao sources. Nanzhao dehuabei, an inscription of stone tablet installed by the Nanzhao king that reviewed the triangle relationship among Nanzhao, Tang, and Tibet, recorded that a tributary mission was sent to Tibet after Nanzhao's victory over the Tang army. It is said that the sixty-person mission presented Tibet with many treasures. As a reward, a Tibetan minister was dispatched to Nanzhao with gold hats, gold horde, gold belts, silk, shells, blanket, horses, sables, silver items, and other local articles.129 In 829, Nanzhao plundered Chengdu and presented Tibet with a gift of 2,000 Shu people as well as other treasures.130 Fan Chuo recorded that big sheep were brought from Tibet.131

71The fame of this road was gained through the tea trade, although many local and exotic goods were circulated on the route. Tea, in the Tibetan language, is pronounced as "ja," the same as that in Japanese, both from ancient Chinese pronunciation. Until the coming of the eighth century, the Tibetan people did not drink tea, even though the king and nobles had tea from China, but not from Yunnan.132 Tea was recorded in Yunnan by Fan Chuo, as the Nanzhao people drank tea boiled with pepper and ginger.133 But there are no clues as to whether tea was exported from Yunnan to Tibet at that time. Neither can we know whether it took place in the Song time when the tea-horse trade in Sichuan was prosperous and later monopolized by the state.

72The Ming-Qing period witnessed the heyday of the tea trade. At that time the Mu clan had risen and dominated the border area between Tibet and Yunnan. Later labeled the Naxi nationality, the Mus, like their predecessors, indeed had close relations with the Tibetan people. Centered in Lijiang, the Mu family was acknowledged by the Mongols and the Ming and the Qing courts. In 1661, the tea-horse trade market was set up in Beishengzhou (Yongsheng), officially recognizing the existing trade. Thanks to the tea-horse trade, many towns prospered; one of these was Lijiang, which had for a long time been the bridge between Yunnan and Tibet.

73It is worth noting that the Tea Horse Route certainly included routes from Sichuan to Tibet. Since Sichuan, Yunnan, and Tibet bordered each other, tea from Sichuan sometimes was shipped first to Yunnan, and then transferred to Tibet; or tea from Yunnan was shipped via Sichuan to Tibet. At first sight, these transfers were unnecessary, but economic supplement and interdependence in the discussed areas made those transactions dynamic and meaningful. One should bear in mind that present administrative boundaries meant nothing to the local peoples at the time. While Tibet consumed the bulk of the tea, a certain amount was sold in Nepal, India, and China proper, too. In fact, the first-class tea produced in Yunnan was for Chinese markets. The Puer tea won a high reputation in Beijing, and was on the list of tributary items presented to the imperial court. Yunnan tea, as a major export, was also shipped into Southeast Asia.134

The SSR in the Yuan-Ming-Qing Period and After

74The discussion above ends before the Yuan Dynasty (except for the Yunnan-Tibet connection) because, following the Mongol conquest, communications among China and its neighbors generated many documents, fully attesting to the existence of the road network at least from this period on. Nonetheless, a look at the communications after the Yuan period will show the historical continuity and development of transactions along the route.

75In 1253, the Mongol cavalry conquered the Dali Kingdom, and in 1276, Yunnan Province was established. However, the Mongols did not stop in Yunnan. They expanded southward into other Southeast Asian states. In order to serve the military conquest and subsequent political control, the Mongols imposed the jam postal (zhanchi) system along the main roads.135 Seventy-eight zhanchi were established in Yunnan, including seventy-four horse stations (mazhan) and four water stations (shuizhan). The former owned 2,345 horses, and thirty oxen, while the latter had twenty-four ships.136 Hence a postal network covered the whole of Yunnan and extended beyond. Indeed seven major postal lines basically characterized the zhanchi system around Yunnan: from Zhongqing (Kunming) via Jianchang (Xichang) to west Sichuan; from Zhongqing via Wumeng (Zhaotong) to Sichuan; from Zhongqing via Guizhou, northward to Dadu (Beijing); from Zhongqing via Guangnan to Yongzhou (Nanning, Guangxi); from Zhongqing via Tonghai to Annam; from Zhongqing via Dali, Yongchang to Burma; and from Zhongqing via Dali to Lijiang.137 In reality these seven lines were routes along the SSR itself.138

76The Ming Empire generally followed the Yuan postal system in Yunnan, except for the postal stations along the road between Yunnan and Annam.139 Every 60 to 80 li, a postal station (yizhan) was set up with one or two dozen horses, managed by a staff of eleven or more. All the expenses for the postal stations were provided by local governments. There were around eighty yizhan in Yunnan through the Ming period, sometimes up to ninety.140 Besides postal stations, bao, or military stations were built, sometimes replacing postal stations.141 During the reign of Wanli (1573–1620), fifty-three bao were stationed in Yunnan, among which thirty-six were along the postal roads and took care of postal services.142 In addition, the Ming court stipulated that xunjiansi, military inspection offices, be set up in the strategic passes for security considerations. Hence many xunjiansi were found, along with postal stations (yizhan) and bao, in the same location.143

77The Qing Dynasty inherited and extended postal stations into native chieftain areas, which the Ming had not yet reached. There were nineteen postal stations (yizhan), twenty bao, and fifty-four military stations (junzhan).144 Between these major stations, pu as small stations were set up every 10, 15, 20, 30, or 40 li, depending on local situations. On the frontier areas where there were no postal stations, pu instead were stationed. Altogether there were over four hundred pu.145

78Examining the Yuan-Ming-Qing period, we can detect the common historical inheritance and development of postal stations and other public communication facilities, even though the territories of the three empires differed. The obvious trend is that over time the postal infrastructure became more comprehensive and systematic, reaching into mountainous areas where ethnic peoples dominated. As a result, a large part of the SSR was incorporated into the official transportation system.

79Official management of roads and postal stations was primarily for military and political goals, but commerce and other cultural communications were by no means less important. First of all, military campaigns and political administration must have accompanied massive material shipping. Furthermore, when the power struggle was over, official interactions between China and Southeast Asia made full use of these roads and services. Chinese documents in this period were filled with records of tributary missions, which is why some roads were named tributary roads (gongdao). As is well known, tributary missions functioned as forms of material exchanges as well as political and cultural interactions. Finally, public management of transportation institutions did not exclude private merchants; rather it benefited private commerce, and as Yu Yingshi points out, "the profit-seeking merchants never failed to use public facilities to serve their private ends."146 The improvement of roads resulted from official involvement, to greater or lesser degrees, and stimulated the transition from commerce of precious items into the commerce of bulk goods, which indeed occurred in the Ming-Qing period.

80A significant contribution of the Southwest Silk Road during the Ming period was the spread of the new crops to China. Ho Ping-Ti, the prominent scholar of Chinese history, has argued that this road during the Ming period (and perhaps throughout Chinese history) was no less important than the Northern Silk Road, as corn and sweet potatoes arrived in China in the end of the sixteenth century firstly through this road.147

81The end of the nineteenth century witnessed the European occupation of mainland Southeast Asia. The expanding European world system had already greatly transformed trade there.148 It was during this period that both the British and French invented the Yunnan myth, which saw Yunnan as the key to their competition in Asia and thus in the world.149 After colonizing Burma and Vietnam, they began to penetrate into Yunnan,150 with plans to build railways or highways that connected Annam or Burma with Yunnan. The Red River was also more fully explored to construct links among Yunnan, Annam, Hong Kong, Canton, and even Tibet.151 Major Davies, after his adventure, proposed a railway connecting India and the Yangzi, a strategic decision for the British Empire in Asia.152 His idea, though never realized, symbolized the feverish ambitions of many colonists. Eventually the French advanced in the colonial rivalry. In 1910, the Dianyue (Yunnan-Annam) Railway was completed. This railway extended 800 kilometers, connecting Kunming with Hanoi, resuming the heyday of the Yunnan-Jiaozhi trade. A large amount of minerals, especially tin, was exported from Yunnan into French Indochina, which served as the foundation of Yunnan economy during the early twentieth century.

82The British, though having failed to build a railway between Yunnan and Burma, succeeded in installing modern transportation in Burma, which considerably stimulated the trade.153 Steamships in the Irrawaddy were busy transporting cotton for Yunnan. For example, when the Yunnan-Tibet connection was blocked due to the turmoil of the 1911 revolution, Yunnan tea was first shipped to Burma and then to Tibet.

83World War II brought unprecedented international attention to the SSR. The nationalist government retreated to Southwest China in 1938. When the Japanese blocked all coastal communications, the SSR contributed greatly to international connections. Before the Japanese occupation of Vietnam in 1940, the Dianyue Railway was China's only access to the sea while the Yunnan-Burma railway and highway were under discussion. The construction of the Yunnan-Burma Railway began in 1938, but was never finished, for many reasons. Nonetheless, the Yunnan-Burma Highway (Dianmian Gonglu) was the major artery for China, especially after the Dianyue Railway was blocked. It was put into use in September 1938, but this ended in May 1942, when the Japanese occupied Burma. Consequently, the Sino-Indian Highway was on the agenda. Its construction moved forward when the war in Burma favored the Allies. January 1945 saw its completion.

84Over 3,000 kilometers long, it started from Ledo in India, continued across Upper Burma, and ended in Kunming. But the most well-known form of transportation may be the Hump Airline that started from Assam, went through valleys of the Himalayas and the Hengduan Mountains, and landed in Yunnan. The airline took over the responsibility of the Yunnan-Burma Highway when the latter was blocked.

85While modern transportation facilities played a significant role, traditional caravans were fully utilized and developed to an unprecedented scale. In 1942, the most difficult part of the war, for China, began. Though the Hump Airline brought a lot of materials, it was unable to meet demands. With no access to Burma after 1942, the Yunnan-Tibet-India connection was the only international passage in Southwest China. Private merchants felt quite patriotic when taking this opportunity to expand their business. Thousands of horses were utilized. International politics had reinstituted the golden age of traditional transportation.

86One episode may suggest the special role Yunnan played in World War II. Yunnan would have provided a wonderland and a promising prospect for hundreds of Jewish refugees in Shanghai. In 1939, a proposal was raised to move 100,000 desperate Jewish people to the remote frontier province, but considered utopian, it was not put into effect.154

87After fifty or so years of isolation, Yunnan and the rest of China are again seeking international access. Taking advantage of its strategic location and its historical closeness with the southern regions, Yunnan is developing a highway connecting China, Southeast Asia, and beyond, attracting internal and international attention once again. This highway, indeed, will start from Xi'an, the symbolic city of the Overland Silk Road, run through Chengdu, Kunming, and Dali, and will reach the Indian Ocean by Southeast Asia.155 Simultaneously, the construction of pipeline for oil from the Middle East through Burma is also being discussed. While the governments attempt to resume their ancient communications, nongovernmental organizations such as international human traffic groups have begun to utilize this road. Some illegal Fujianese immigrants left their southeast coastal homes, went to Yunnan, crossed the border, entered Burma or Thailand, and transferred to some place in Latin America before their arrival in the United States. Traffic of women for prostitution in Thailand follows these routes as well.

The Horse Trade: A Case Study of the SSR

88We have established a general map of the geographic location and historical development of the Southwest Silk Road, especially before the medieval period. Diverse materials circulated on the trade routes, including shell, jade, precious stones, elephants, elephant tusks, horses, lumber, cloth, herbs, spices, salt, tea, gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, cotton, and opium, just to list some of the most familiar products. While discussion of all of the items are beyond the scope of the chapter, the following section will examine the horse trade as a means to examine the dynamics of the SSR. By looking at existing Chinese and non-Chinese scholarship, I seek to illustrate how trade along the SSR indeed shaped local societies.

89The horse was a famous local animal in Yunnan, and according to Sima Qian, a source of wealth, along with slaves and oxen, for people west of the Dian. Horses entered Yunnan with prehistoric migration from Central Asian grasslands.156 After centuries of adaptation, horses in Yunnan could be divided into two types: one found in northwest Yunnan where the climate is cool, the other in southern Yunnan where the climate is subtropical.157 Archaeological evidence reveals that horse husbandry became popular as early as the sixth century BCE. Horses were also used in wars and for transportation.158

90Horses in Yunnan had been well known to the Chinese since the Han Dynasty. During the early Western Han horses were reportedly exported to Sichuan.159 Legends recorded in HYGZ and HHS talk about shenma (divine horses) in Dian Lake, which may imply that horses were valued by the indigenous people as early as the third century.160 Chinese sources also suggest the prosperity of husbandry, as at one time 100,000 head of oxen, horses, and sheep were presented to the Han Dynasty.161 Since the third century, records of horses in Yunnan have been available in Chinese documents. Riding Yunnan/Sichuan horses became fashionable for nobles in the Central Plain, while horses served as instruments of war for local regimes.162

91Sources of the Tang/Nanzhao period documented the roles of horses in local society. For example, Nanzhao presented horses as tributary items to the Tang court.163 Both Man Shu and Xin Tang Shu list the Yuedan horse as the best.164 Yuedan was in the former Ailao area, that is, today's Tengchong. Zhou Qufei in his Lingwai Daida provided more details about the Yunnan horse in the Dali/Song period (mid-tenth to mid-thirteenth century). He concluded that the further northwest, the better the horses. Southern horses, according to his evaluation, were not as durable as northeastern ones. However, he admitted that the best southern horses surpassed northern horses, and were worth several dozen taels of gold.165 In fact, the Song court highly valued Yunnan horses, perceiving them to be as good as those from the north.166

92Chinese people had long desired horses from Central Asia, since most areas of the Chinese realm did not produce horses, which were animals of high commercial, but more importantly, military value.167 South China did not produce horses, which might partially account for the fact that southern-based kingdoms seldom managed to resist northern invasions. Yunnan, south of the Yangzi River, was an important exception, thanks to its unique geography. No wonder southern kingdoms were eager to get access to Yunnan horses. There are the two classic cases, one of the Three Kingdoms period (220–265) and the other of the Dali/Song period.