Table of Contents

Media Index

CHAPTER 3

Francis Lieber (1800-1872) was an American law professor whose work became the basis for United States Army prisoner of war general orders during the Civil War.

Official photograph of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (1868-1918), ruler of the tsarist empire from 1894 to 1917.

Photograph of Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1918), President of the United States from 1901 to 1909, and an ardent supporter of the Allies in World War I.

Exterior view of the American Embassy in Berlin during World War I. This building was the old Schwabach Palace, located on the Wilhelm Square, which the U.S. Ambassador, James W. Gerard, rented as his residence and embassy. This building became a beehive of activity in August 1914 as most the European Great Powers went to war and the United States Government assmed responsibility for many Allied interests.

Portrait of James W. Gerard (1867-1951), United States ambassador to Berlin from 1913 to February 1917.

Group portrait of Ambassador James W. Gerard (seated center) and the U.S. embassy staff in Berlin in 1916. Many of these men were responsible for conducting prison camp inspections on behalf of the Entente governments during World War I.

American volunteers and embassy staff members work in the ballroom of the U.S. Emabssy in Berlin in August 1914. with the outbreak of the war, thousands of American tourists sought to return home and the staff soon found itself overwhelmed by the demands of overseeing Allied interests in Germany.

A group of French prisoners mark time in a German prison camp. While they all serve in the French army, the men to the right are colonial troops from Africa and those to the left are from France.

Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg (1856-1921), Chancellor of Germany (in the military uniform) speaks to Dr. Helfferich while Gottlieb von Jagow, the Foreign Secretary, stands in the back.

The Germans incarcerated a global collection of prisoners of war. These soldiers came from North Africa, Serbia, sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, and France to fight against the Kaiser.

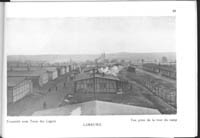

This photograph provides a general overview of the prison camp at Limburg, showing the one-story barracks which accommodated the prisoners. In the background is the twin-spired cathedral in Limburg, overlooking the Lahn River.

A group of Scottish and English prisoners of war relax in the compound at Doeberitz smoking their pipes and cigarettes. Note the German non-commissioned officer standing to the extreme right smoking a cigarette.

William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925), the Democratic Party's standard bearer in three presidential elections, served as Secretary of State for the first two years of the Wilson administration. Bryan expressed reservations about the YMCA's prisoner-of-war diplomacy due to his concerns regarding the maintenance of American neutrality.

Two American officers, Major Harry Brown (left) and Major Dirk Bruins (right) sit on a bench outside of their barrack at Villingen with Major Sarda (center) of the Spanish Artillery. The Spanish government assumed responsibility for American interests in Germany after the Wilson administration severed diplomatic relations with Berlin in February 1917. As a neutral official, Major Sarda inspected German prison camps on behalf of the U.S. government.

Portrait of Walter Hines Page (1855-1918), United States ambassador to Great Brtiain from 1913 to 1918.

Joseph Clark Grew (1880-1965), standing at the extreme right, was the U.S. embassy secretary in Berlin and was responsible for conducting inspection tours of German prison camps on behalf of many of the Allied governments.

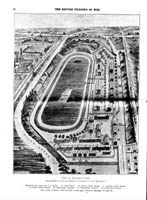

Aerial view of the prison camp at Ruhleben which housed British and Commonwealth interned civilians during World War I. This drawing shows the race track, grand stands, barracks, casino, tea house, New Town, guard room gates, and hospital, which made up the buildings of the prison camp. The Association constructed a YMCA Hall on the open ground between Barracks II and XI.

A group of Allied prisoners of war gather for one last meeting at the YMCA hut at the internment camp in Muerren in Switzerland. Most of these men were sick or seriously wounded and were leaving the next day to return home as part of an exchange program for invalids.

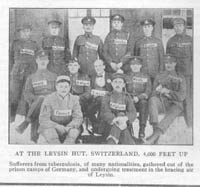

A YMCA secretary sits in the middle of twelve Allied prisoners of war from Australia, Beglium, Canada, England, France, Ireland, Montenegro, New Zealand, North America, Russia, Scotland, and Wales, at the internment camp at Leysin, Switzerland. The Association constructed the hut for Allied internees, many of whom suffered from tuberculosis. Medical authorities believed that the air and high altitude (4,000 feet above sea level) were ideal conditions to treat these men.

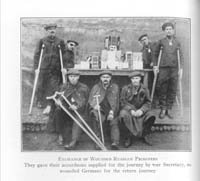

These wounded Russian prisoners of war prepare for their journey home in exchange for wounded German prisoners in neutral Sweden. These men were gravely wounded and would not be able to resume military service; remaining in Germany made them burden for their hosts. A YMCA secretary provided these POW's with the three accordions on the table. The Russians gave the musical instruments to the German prisoners to enjoy during their journey home.

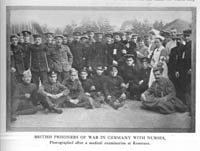

British, French, and Russian prisoners of war pose for a group photograph with two German nurses in the prison compound at Konstanz. Most of these men were seriously sick or wounded and awaited their last medical examination in Germany. Konstanz was a transfer station for prisoners bound for internment in Switzerland for the duration of the war.

Irish prisoners of war kneel for communion from a Roman Catholic priest during an outdoor service in the prison camp compound at Limburg. The altar stands behind the clergymen as the rest of the prisoners stand in prayer.

POW's struggled to build any kind of shelter to protect themselves from the elements when the Germans first opened the prison camp at Sennelager. In this sketch, the prisoners have improvised using earth dugouts and pieces of wood to construct crude huts.

This photograph shows the "tent prison" (Zeltlager) where some Allied prisoners lived during the construction of the prison camp at Guestrow during the winter of 1914-1915. The Germans expected the war to be short in duration and did not anticipate the incarceration of millions of Allied prisoners. As Entente POW's poured into Germany, the prisoners went to work constructing prison facilities. The assignment of prisoners to tents, especially during the winter, led to a number of protests from Allied governments.

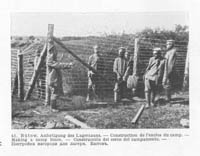

Russian prisoners install posts and unroll barbed wire to enclose the prison compound at Buetow. The POW's provided the labor for the construction of prison camps.

French, Belgian, and British prisoners of war sit in a field which will become the prison camp at Minden in October 1914. The Germans have erected posts and hung barbed-wire around the perimeter of the facility, but the prisoners are living in the tents in the background. The POW's provided the bulk of the labor for the construction of the barracks and other buildings needed to support prison camp operations.

These Russian prisoners are heartily enjoying their meal of soup in the compound of a German prison camp. By the end of the war, most Russian prisoners were constantly hungry because they did not receive parcels from home to supplement their daily rations and were known to scavage garbage dumps for food scraps.

Russian and Romanian prisoners of war assemble in a German prison camp compound. Note that some of the men are wearing rags on their feet instead of boots, despite the cold.

These two tables reflect the national nutritional standards of the German people during the early years of World War I. Dr. Rubner compiled these statistics and presented them to a conference of German POW Department officers in Berlin. These statistics became the basis for food distribution in German prison camps.

Dr. Rubner also compiled the statistics for these three tables which outline food consumption, caloric intake, and protein consumption of German subjects by 1915. This information was presented at a conference of Geramn officers from POW camps and were used to determine food rations for Allied prisoners.

This table shows the reductions in German food rations between April 1915 and June 1919 for a variety of foods. The statistics clearly indicate the effectiveness of the Allied blockade of German food imports as people had to give up a variety of foods. Prisoners of war also experienced these food shortages, although Allied prisoners received the same rations as German troops. While the reduction in rations had little effect on American, British, and French POW's, because they received regular food parcels from home, the impact of lowered nutritional standards had a serious impact on Russian, Serbian, Romanian, and Italian prisoners.

This table shows the reductions in German food rations between April 1915 and June 1919 for a variety of foods. The statistics clearly indicate the effectiveness of the Allied blockade of German food imports as people had to give up a variety of foods. Prisoners of war also experienced these food shortages, although Allied prisoners received the same rations as German troops. While the reduction in rations had little effect on American, British, and French POW's, because they received regular food parcels from home, the impact of lowered nutritional standards had a serious impact on Russian, Serbian, Romanian, and Italian prisoners.

Russian prisoners of war plant seeds in a newly ploughed field on a German farm. Prisoners engaged in agricultural work were not paid as well as POW's who worked in factories, but farm workers enjoyed better meals in relation to their comrades back in the prison camps.

French prisoners, from the captured garrison at Montmedy, work on repairing a railroad tunnel which French troops destroyed during their retreat. This tunnel was part of the Aachen-Paris railway line and was one kilometer long.

A drawing by Louis Raemacker shows German guards herding Belgian workers into a railroad car for transportation into Germany. The laborers bid farewell to their families and will soon be sent off to support the German war effort.

These two Romanian prisoners of war are typical examples of captured soldiers on the Romanian front. They arrived in German prison camps in coats missing buttons and wearing rags to keep warm.

Two mobile disinfection machines stand outside the barracks in the compound at Sagan. The sanitary personnel "shovel" prisoner clothing from the baskets into the disinfection chamber to avoid contamination. The prevention of epidemics was a high priority for German prison administrators and the disinfection machines helped kill lice and other conveyers of disease.

Russian prisoners of war place POW clothing into a disinfection chamber in an unidentified German prison camp. German non-commissioned officers supervise their work as one of the prisoners handles the clothing with a pole. Disinfection was a critical procedure to prevent the outbreak of contagious diseases in cramped prison camps.

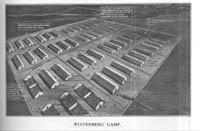

This drawing shows the layout of the prison camp at Wittenberg and highlights some of the deficiencies of the facility, which contributed to the horrors of the typhus epidemic. Many of the stoves in the camp lacked fuel, prisoners had to wash outdoors in water troughs, and there was a lack of mattresses in the hospital. The cemetery in the prison camp is a testament to the viciousness of the epidemic. The main entrance to the prison camp is unique in relation to other facilities in that POW's, staff, and visitors had to cross a bridge over the barbed-wire fences.

These four Russian prisoners of war just arrived in a German prison camp and are about to undergo the sanitation process. German medical officers sought to prevent the outbreak of epidemics in prison camps and the hygiene of arriving prisoners was the first order of business in the facility.

The same four Russian prisoners after they went through the disinfection process in a German prison camp. At the disinfection station, German doctors inspected the men for any illnesses and would have assigned those suspected of carrying disease to a quarantine ward. Healthy men then surrendered their clothing and took showers or chemical baths to clean their bodies. The next step in the process was a visit to a barber who shaved off their hair and beards to prevent the introduction of lice into the camp. Before departing the disinfection station, the POW's received their disinfected uniforms or new clothing if their uniforms were unsalvageable.

A prisoner and a German soldier remove clean clothing from a disinfection machine in the prison camp at Limburg. These clothes have been fumigated and are safe to return to their owners, now that they are free of vermin which might have spread disease in the camp.

Prisoners of war take showers at Limburg; the ever present German guard stands in the center background. The picture is staged; the prisoners do not appear to have any soap and are modestly dressed for the photograph.

Albert Beveridge (1862-1927), center, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana, conducted an inspection of German prison camps during World War I; he is flanked by a French prisoner at the left and a Russian POW at the right.

French orderlies pose with the patients in the hospital ward in the prison camp at Friedrichsfeld. All of the beds are filled with sick and wounded prisoners, but only one patient appears to be too ill to sit up in his bed.

Two wounded French prisoners play chess in the ward of a German hospital. Their moves are closely watched by another French patient and a German soldier in a Pickelhaube. The ward is full of recovering patients.

A German medical officer vaccinates Belgian and French prisoners against cholera in the prison camp in Chemnitz. Epidemics raged quickly through prison camps due to the close proximity of prisoners in cramped barracks and German medical staffs took preventative measures to ensure healthy prison camps.

Scottish prisoners of war receive holiday parcels from their families and friends after the packages passed through the German censors. Many families commissioned the YMCA to provide parcels containing food and clothing not included in Red Cross parcels. This additional food and clothing significantly improved these prisoners' standard of living inside the prison camps.

This French poster promotes a modern art exhibition in March 1916 in which the proceeds will go to provide clothing for French prisoners of war in German prison camps. The poster shows the distribution of relief parcels in a prison camp under German supervision. To the left, a French POW writes a letter, perhaps requesting some kind of aid from home.

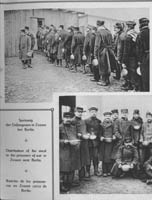

Belgian and French prisoners wait patiently in line outside of the kitchen in Zossen to receive a bowl of soup. The same prisoners happily pose for a picture with hot soup after receiving their meals in the kitchen.