|

| |

|

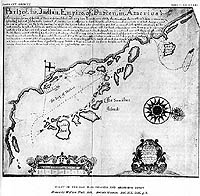

When four Scottish ships arrived to colonize the Darién in late 1698, the invaders challenged the carefully constructed "official story" of the incremental conquest of the Darién. In addition, to make things worse for the Spanish, the audacious Scottish move prompted the English state to enter the region, albeit in a limited fashion. These English and Scottish maneuvers followed decades of Spanish and pirate involvement with the newly emergent Tule leaders. The English-speaking colonial latecomers would interact with indigenous men who possessed more experience at alliance-making than they did. As they would learn to their peril, the Indians of the region had not yet been forced to accept European rules and practices, though they had been dealing with Europeans for some time. Whether the Anglophone newcomers realized it or not, they were stepping onto native ground when they arrived in the Darién, and they would have to learn how things were done if they were to succeed. Previous treatments of what has come to be known as the Scottish Darién Scheme have presented the Indians of the isthmus as the minor characters (comical, and prone to drink) in a colorful New World drama that provided, at best, a sidelight to a narrative of Scottish history. The Tule, however, were never peripheral to the Darién Company’s activities. This chapter is a study of the brand of rainforest diplomacy that the English, Scottish, and Spanish negotiators engaged in with Tule leaders in order to survive. 1 | 1 |

The British seamen who came to the Darién operated under an imperial ideology that had first been articulated by Sir Walter Ralegh 2 at the close of the sixteenth century. Ralegh grounded his theory on an utter internalization of the Black Legend, believing that the misdeeds of the brutal Spanish had done the greater portion of the English colonizers’ task for them. 3 Because the Spanish had earned the undying enmity of the indigenous population by mistreating them for centuries, Ralegh suggested that Englishmen should offer alliances to the hard-pressed Indians, accept them as the American vassals of the English crown, and put them to use as shock troops to attack and harass the Spanish throughout the Indies. Minor effort, Ralegh had argued, coupled with a bit of restraint would lead to the consolidation of an English South American empire. 4 The British seamen who came to the Darién operated under an imperial ideology that had first been articulated by Sir Walter Ralegh 2 at the close of the sixteenth century. Ralegh grounded his theory on an utter internalization of the Black Legend, believing that the misdeeds of the brutal Spanish had done the greater portion of the English colonizers’ task for them. 3 Because the Spanish had earned the undying enmity of the indigenous population by mistreating them for centuries, Ralegh suggested that Englishmen should offer alliances to the hard-pressed Indians, accept them as the American vassals of the English crown, and put them to use as shock troops to attack and harass the Spanish throughout the Indies. Minor effort, Ralegh had argued, coupled with a bit of restraint would lead to the consolidation of an English South American empire. 4 | |

|

Ralegh’s imperial vision, steeped in the stark black-and-white opposition inherent in the Black Legend, was blind to the complicated reality of the Americas. Though enlightened in the sense that it posited good treatment of the Indians as a means of winning them over as allies, it was marred by a racialist vision that was unable to imagine Amerindians taking an active role in shaping their own futures. The Tule of Darién were by no means the passive victims the Britons expected to find, and chaos resulted from the many layers of Anglo-Scottish misunderstandings. | |

|

By the time the Britons arrived in the 1690s, astute Tule leaders had been engaged in an often-shifting and intricate process of working to integrate European newcomers into an already emerging system of native alliances and diplomatic exchanges. The outsiders had their greatest difficulty in recognizing that the Tule did not seek relations with Europeans in order to help one kingdom succeed at the expense of another. Instead, they sought ways to integrate the region’s newcomers into existing indigenous political and diplomatic systems, or to deploy them as allies in order to better their position within that system. | |

|

Jockeying to attain and deploy Amerindian pawns on this American front of the global chess game against the Spanish, Captain Richard Long (under a commission from the king of England), and Commodore Robert Pennycook (the senior representative of the Council of the Scottish colony in Darién), were doomed by their adherence to the Raleghan vision to create a warped and ultimately counterproductive mental picture of Darién’s geopolitical situation. This had profound consequences, for these men never grasped the nature of the complex system into which they were inserting themselves, and they lacked the numbers or the power to recast it even to approach their preconceived image. 5 The Scottish Choice of the Darién | 5 |

|

On June 26, 1695, the Scottish Parliament passed an act incorporating the Company Trading to Africa and the Indies. The Act named the twenty directors of the Company, a group split evenly between Scots and London merchants. Most contemporary observers assumed that Scottish attempts at international trade and settlement would focus on the edges of the East India Company’s sphere of operations in the East Indies. 6 A few more perceptive observers, however, taking note of the name of William Paterson among the list of directors, would know exactly where the Scottish Company was bound to direct its efforts. | |

|

Paterson had been one of the founders of the Bank of England in 1694, and he held a high reputation in City financial circles. This, coupled with his trade contacts around the world and his tireless enthusiasm for a Scottish trading company, established him as the leader of the London merchants holding an interest in the new Scottish company. 7 It would be incorrect, however, to argue that Paterson, or any other London merchant, was the sole mastermind directing the affairs of the Scottish colonial endeavor. 8 There were too many Scottish merchants, statesmen, and politicians engaged in the activities of the Company for any man or group from London to dominate its affairs. | |

|

Paterson, however, was instrumental in convincing the other directors of the Company to focus their enterprise’s initial activities on the Americas. The force of his arguments led the Company to place the linchpin Scottish settlement on the Isthmus of Darién. Carried away by his reputation, expertise, and the copious documentation he marshaled to back up his argument, the directors intertwined the fate of the Scottish Company Trading to Africa and the Indies with that of a projector as tenacious, tireless, and single-minded as the late seventeenth century could produce. 9 | |

|

Paterson would admit in 1701 that for seventeen years he had earnestly sought institutional and financial backing for a north-European trading empire with its central entrepôt on the Darién isthmus. He had made this case before numerous European courts, companies, and parliaments to no avail until 1696. 10 Paterson envisioned a trading nation based in the Americas with a New World Amsterdam at its center. This vital trade port would restrict neither religion nor the movement of ideas and would naturalize as citizens merchants and factors of all foreign nations agreeing to abide under its laws. At this conveniently placed American emporium, Eastern luxury goods would be traded for grains, slaves, and precious metals. | |

|

By the end of July 1696 Paterson had convinced the Scottish directors that rather than organize their trade along routes centering on the East Indies, the Isthmus of Darién was the best site to choose. The directors’ minutes reported on July 23, 1696, that | 10 |

| |

| |

|

Paterson’s vision of a pan-British company, uniting the skills and funds of English and Scottish merchants, was not shared by the English Parliament. The House of Lords objected strenuously to the presence of English merchants on the list of directors of a Scottish enterprise that appeared to be so obviously "prejudicial to the Trade of this Kingdom." 12 On December 3, 1695, the upper house opened hearings into the matter, questioning the merchants named in the Act and taking evidence from English East India Company merchants. These men, not surprisingly, condemned the Scottish enterprise as a nefarious front operation controlled by a group of London-based interlopers aiming to disrupt their monopoly. | |

|

On December 12 the Lords drafted an angry address to the king and requested a conference with the House of Commons. Representatives from both houses subsequently presented a formal address to William III on December 17, informing him of the grave threat the incorporation of the Scottish East India Company posed to the realm. Offering a response in full accord with the temper of the address, William tersely and acerbically stated in his reply that "I have been ill served in Scotland, but I hope some remedies may be found to prevent the inconveniences which may arise from this Act." 13 Taking this as their cue, English lawmakers immediately proceeded to enact statutes preventing any English involvement, financial or otherwise, in the Scottish endeavor. 14 | |

|

Originally projected to draw half of its capitalization of £600,000 from English sources, the Scottish Company was forced to lower its financial sights to £400,000, with all of this deriving from Scotland. This figure was alarmingly small for a company whose charter empowered its directors to plant colonies, erect cities and towns, and to construct forts. Yet, even the reduced figure presented a tall order to the northern kingdom. In a testament to the national enthusiasm for the endeavor, not only was the entire £400,000 pledged by individual investors, but nearly half of the sum was also actually collected by the Company. Tellingly, this £170,000 equaled the entire amount the Scots had invested in manufacturing over the fourteen years from 1681 to 1695, a period during which the Scottish government and its ruling class actively promoted indigenous industries. 15 | 15 |

|

By the summer of 1696 the Company had gone through several significant changes. No longer an international trading company based in London, it became a Scottish national concern. From a firm capitalized by £600,000 drawn equally from English and Scots investors, it evolved into a hard-pressed concern aiming to draw all of its projected capital of £400,000 from the poorer northern kingdom. Most importantly, contrary to the assumptions of the House of Lords and other initial observers, the Scottish Company Trading to Africa and the Indies through the course of the fall of 1695 decisively moved its sights away from the East Indies and steered an unsteady course directly toward the Spanish West Indies. The English Make it a Race for Darién | |

|

The Scottish directors, enjoining all involved to keep matters strictly secret, dispatched William Paterson and several others in 1697 to Amsterdam and Hamburg to acquire ships and to raise funds for the Company. Though successful in procuring ships for the Company’s service, the commissioners failed miserably in carrying out the other two instructions. Foreign investment was not forthcoming in the face of English interference and hostility, and the activities of these agents were common knowledge, and reported back to the English and Spanish governments. 16 | |

|

The English Resident in Hamburg, Sir Paul Rycaut, kept a close eye on the Company’s commissioners, and in an extensive correspondence with the English Secretary to the Board of Trade William Blathwayt he reported on these activities in detail. On April 30 Mr. Orth, Rycaut’s secretary, wrote to Blathwayt that "the truth was that [the Scots] intended but very little trade in the East Indies nor Africa, that they only had added these to disguise their true intentions which are to trade in America." 17 James Vernon, in a note written on May 20 and added as an enclosure to Orth’s letter, put the matter in the most specific of terms for the Board of Trade, adding that he had consulted with Mr. Blathwayt, secretary to the Board of Trade, who "intimat[ed] that [the Scots] project is to send to the Straits of Darién and to enter into a league with the Prince there in order to exercise hostilities and depredations upon the Spaniards." 18 The English were not the only ones to attain this detailed knowledge of the Company’s plans; the Spanish resident in Hamburg, Don Francisco Antonio Navarro, was privy to exactly the same information, which he forwarded to the Spanish crown. 19 | |

|

Remarkably, the source of much of this information was almost certainly William Paterson himself. Not only did he have a merchant’s penchant for exchanging bits of juicy information at the coffeehouse, but he also felt that secrecy was the wrong way to entice potential investors to the Company. Because the Darién entrepôt was to be the centerpiece of a fully open trade system, it followed that everything related to the system need to be equally open. Merchants from around the world were not only being asked to invest in the Company, but they would also be required to settle or send factors to the new territories under the Company’s auspices. Men being asked to take such risks needed to be fully informed about the nature of the enterprise in which they were becoming involved. 20 | |

|

This had been Paterson’s practice for more than a decade, as Robert Douglas, a Scottish merchant resident in London with interests in the East India trade, informed the directors. In a letter dated 5 September 1696, he remarked that the inclusion of Paterson on the Company’s Court of directors made the focus of their activities an open secret, for he himself knew of | 20 |

| |

|

So far I have charted the means through which the English government gained the information that the Scots intended to found a settlement on the Isthmus of Darién. This was not the only strand of English interest in the region, however. The exploits of Sir Francis Drake in the sixteenth century, and Sir Henry Morgan in the seventeenth, had made the name Darién synonymous with the Achilles’ heel of the Spanish empire. | |

|

William Dampier’s A New Voyage Round the World, published in 1697, galvanized English thinking about Darién. 22 Dampier, who had been a member of the pirate band to which Lionel Wafer had been attached, published his memoir in February, and by May the book was in its third edition. 23 Seeking a powerful patron, Dampier dedicated the text to Charles Montague, President of the Royal Society. In turn Montague "recommended [Dampier] to the Treasurer of the Navy, the Earl of Orford, and got him a position at the Custom’s House" in August of 1697. 24 Dampier became a social celebrity, and influential patrons jockeyed to procure him as a dinner guest. 25 | |

|

Dampier’s New Voyage, while purporting to be an adventure story about a band of English pirates, was filled with details of the geography, topography, fauna and flora, and soil of the isthmus and the South Sea. Dampier, like his buccaneer companion Lionel Wafer, in fact wrote his text as a user’s manual for future expansionists operating in the area in response to the "Directions for Seamen Bound for Far Voyages" and the "General Heads for a Natural History of a Country, Small or Great, proposed by Mr. Boyle" which had appeared in the first volume of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions. 26 | |

|

The Royal Society posited itself as the clearinghouse for information that might at a future date be useful to the state in order to dispel the rumor and fantasy that had attached to the accounts of endeavors such as those of Drake and Morgan. Pointing up the veracity of his text, Dampier stated in the preface that | 25 |

| |

|

As he had intended, Dampier’s publication caught the eye not only of a reading public hungry for the tales of adventure being produced by a coterie of London printers, but also of the bureaucrats sitting on the recently restructured Board of Trade and Plantations. 28 The information provided by Orth’s letters prodded the members of the Board to interview men resident in the British Isles who had spent any amount of time on the Darién isthmus. The Board had knowledge of Wafer because of Dampier’s mention in his preface that "I might have given a further Account of several things relating to this Country; the Inland Parts of which are so little known to the Europeans. But I shall leave this province to Mr. Wafer, who made a longer Abode in it than I, and is better able to do it than any Man that I know, and is now preparing a particular Description of this Country for the Press." 29 | |

|

One month following the publication of the third edition of his book, the Board "ordered for Mr. Dampier, who hath lately printed a book of his voyages, to attend Friday next, and give notice to Mr. Wafer, that they may be examined as to the design of the Scotch East India Company to make a settlement on the Isthmus of Darién." 30 The two ex-buccaneers were examined by the Board of Trade on July 2, 1697, and they provided "an account of the Isthmus of Darién and its country between it and Portobello, which they were desired to draw up in writing." 31 Impressed in particular by Wafer’s testimony, in which he maintained that as few as five hundred men could wrest the isthmus from the Spaniards and hold it, the Board’s thinking regarding Darién crystallized. Armed with the testimonials of Dampier and Wafer, the published writings of Bartholomew Sharpe, 32 and the assorted accounts gathered in the English edition of Exquemeling’s book on the buccaneers, 33 the Lords of Trade ordered on September 10, 1697, that "on intimation of the importance of Golden Island and of the port upon the Main over against it, in case of any settlement by any nation on the Isthmus of Darién, a representation was ordered that a competent number of men should be sent from England or Jamaica to seize the port and island for the Crown of England." 34 | |

|

Although the crown never ordered a military action to conquer Darién, it did keep its options open regarding the region. At the same time the Board was making its suggestion, Captain Richard Long, an English mariner with previous experience in the Caribbean, independently proposed an expedition aimed at recovering wrecked silver ships off the north coast of Darién. Although he crafted his proposal without knowing of the Board’s recent interest in the Darién region, the time was right for any proposal that promoted English activity in Darién, however modest. In the month of May his proposals were debated by the Admiralty, Treasury, and the Privy Council. 35 On July 13 the Lords Justices of the Realm "ordered that a copy of the memorial be sent to the Admiralty, so that they may comply with it as far as they think convenient." 36 | |

|

In the midst of the English moves to enlist Long to begin operations in Darién, the directors of the Scottish Company were engaging in equally purposeful planning. In the spring of 1698 Lionel Wafer traveled from London to Edinburgh to be questioned by the directors. Wafer unsuccessfully sought £750 for two year’s service for the Company, with £50 to be paid to him immediately upon his being hired. The Company records reveal that on April 19, 1698, "a letter was presented and read … containing some proposals made by one Mr. Wafer for serving this company, upon due consideration whereof, Resolved (nemine contradicente) that this company do not employ the said Mr. Wafer in their service, and the company’s secretary is hereby ordered to signify the same by a letter." 37 | 30 |

|

Wafer’s interaction with the Company’s directors, though unfruitful, did not escape the notice of the Board of Trade. On June 30, 1698, an anonymous writer from Edinburgh warned that "here are great preparations at hand and much tampering with some in London, especially on Mr. Waffer [sic]. I am sure overtures have been made to him, though I find no encouragement he has given them yet, but whether this be from respect to his country or from expectation of a gratuity from the publication of his book I know not. I am certain money has been offered to him and things discoursed to him, so I desire that he be examined forthwith, for Scotch ships will sail in less than a month’s time." 38 This letter was read before the Board on July 12, 1698, and William Dampier was immediately ordered to attend. Dampier appeared before them the very next day, reporting "that he knew nothing of proposals made to Mr. Wafer." Dampier also bluntly remarked that he did not think Wafer "capable of doing the Scotch East India Company any great service." 39 Possessing the Darién | |

|

On May 8, 1697, Secretary James Vernon forwarded to the Lords Justices of the Realm a Proposal from Richard Long. In it the Quaker seaman, Long, discussed the "great possibility of discovering gold in the coast of America, where no Europeans had yet settled, as also that he had knowledge of a plate wreck or two." 40 Captain Long was readily granted his commission and a ship, the Rupert prize, and on December 5, 1697, set sail for the Americas. 41 Historians of the Scottish Company have unfortunately passed over Long’s activities because they have taken the disparaging comments of Long’s contemporary critics at face value. 42 | |

|

Scotsmen, intent on creating a different type of empire in the New World, depicted Long as the living embodiment of the morally and physically corrupt English and Spanish empires they hoped their efforts would supersede. A Scottish rival who encountered Long in the midst of his expedition rendered his character in a withering thumbnail sketch, stating that "whatever the King or government of England may have found in Captain Long we know not, but to us in all his conversation he appeared a most ridiculous shallow-pated fellow, laughed at and despised to his very face by his own officers and continually drunk." 43 | |

|

Historians have taken this sketch to be an accurate, eyewitness depiction of the Quaker captain’s behavior, rather than interpreting it as a deft bit of character assassination carried out by an interested rival. Due to this vivid, negative assessment of his character, Long’s account has been ignored by historians. However, when it is read in conjunction with the Scottish diaries, letters, and the Spanish sources generated by the Scottish incursion, it provides considerable insight into the Tule geopolitics of the Darién, which have not been well understood. 44 | |

|

At the end of September 1698, Richard Long was at Port Moranto in Jamaica, a place made famous as the staging ground for buccaneer assaults on the Darién in the 1680s. Here, Long related, "an opportunity accidentally happened contrary to [my] expectation and very intent of [my] voyage that encouraged [me] to sail for Darién." 45 The Quaker skipper abandoned the hunt for sunken treasure on the Caribbean coast and dedicated himself to a novel interpretation of the second portion of his commission, which enjoined him to seek a gold coast. | 35 |

|

In explaining his deviation from the strict terms of the commission, Long would later argue that the Darién coast was in fact a golden one, though none of that metal had yet been mined for England. He stated the goal in geopolitical terms, arguing that "if the Gulf and great river Darién do lie vacant as it hath done since the Spaniards enjoyed America it may be well for England, but if it … should be possessed by any other nation it would prove an unhappy thing to England." 46 Long had decided, on hearing at Port Moranto of a familiarity between the French buccaneers and the Tule Indians on the Darién coast, that it was imperative for him to take possession of the region in the name of the English crown. | |

|

The Englishman was especially alarmed by the knowledge that "in the northwest of Darién there is of late years always some French buccaneers … from eighteen to forty leagues distance from [Golden Island] … who are mightily admired of the Indians and they take Indian women to their wives … and many of the principal Indians go by French names." 47 French mariners were no strangers to Darién, having had an interest in the Americas, and the isthmus in particular, since the sixteenth century. In fact, the English buccaneers operating on the isthmus in the seventeenth century worked in close concert with Frenchmen, sharing their occupation, risks, and burdens. These French buccaneers were by no means representatives of the French state or government, which never was, in the end, willing to sacrifice crown interests to those of corsairs when conditions in Europe changed. 48 | |

|

At Port Moranto, Long met a group of French buccaneers who had lived among the Indians, and who "discoursed … about the affairs of Darién and they informed me of two great divisions that had been … many years … and that they were then making a peace and to join together to go against the Spaniards to take a gold mine that belongs to the Spaniard that lay on the South Sea part of the country." 49 Long asked the Frenchmen to pilot him to their living places on the San Blas coast, but they understandably refused. The Englishman had to choose as his pilot one of the men who had brought the Frenchmen in the Jamaica sloop. He left Jamaica on September 27, 1698. | |

|

By the first of October Long had anchored the Rupert against the Río Coco, "which was the principal place of the French buccaneers…. I fired two guns … as the French used to do to give notice to the Indians to come down to me." 50 Long had prior knowledge of an Indian named Corbette 51 who had been a slave in Jamaica and, it was rumored, held a commission from the French king himself. 52 The wary Indians who boarded the Rupert on October 9 were kindly entertained by the Englishman, and revealed, instead, that a man named "Ambrosio" 53 was their head captain or general. They also informed Long that there was with them "one French man and a French mulatta and the Golden Island Indians and other Indians living up in the Gulf in company with them." 54 | |

|

Long had quickly come face to face with the reality that many a European traveler who dealt with Tule had to accept. Englishmen expected to find kings and emperors enthroned throughout the Americas. This expectation was based on their own ruling system and the well-known examples of Mexico and Peru, which Ralegh had studied closely. 55 The royalist assumption had been given further impetus in the Darién by the stories recently spread in print by the buccaneer Bartholomew Sharpe that a single, powerful ruler governed all of the Indians of the region. 56 Long seems to have expected that Corbette, of whom he had prior knowledge, would be that man. Instead he had been informed that Ambrosio was the head captain of the San Blas Indians, and that Corbette was to be found at home six leagues to the west of Long’s present position. | 40 |

|

Long did not have to seek out Corbette, for two days later that Indian leader, who spoke good French, came aboard the Rupert of his own accord. Having been entertained and given presents by the Quaker captain, the next day Corbette even "promised he would go with me to the Gulf." 57 Long spent many hours in conversation with Corbette and his father-in-law, a man named Martin, and the three agreed that when Long returned from the Gulf of Darién "Corbette’s brother-in-law should go with [him] for Jamaica … to treat with the governor if he would send people to Darién to inhabit among them and to settle the country." 58 Long’s own account reveals the complications he was facing in this multilingual form of international diplomacy. Corbette clearly had not agreed to have Jamaica planters populate his lands in great numbers, as Long had written that he had done. The Tule leader had not even agreed to go to the Gulf with Long, for not much later, after the aforementioned affirmative statement ("Corbette promised to go"), Long writes that "I could not prevail with Capt. Corbette to go to the Gulf." 59 | |

|

In the meantime another Tule leader named Captain Pedro, accompanied by a Frenchman, kept up the procession and visited Long aboard the Rupert. It must have seemed to Long that, in an inversion of his original assumption, the Darién had as many leaders as it had rivers. 60 Pedro spoke Spanish well, and he informed Long that Captain Ambrosio had not gone to seek gold in the Gulf, as he had assumed, and was in fact close on Pedro’s heels and would arrive soon. Pedro’s interaction with Corbette allowed Long to witness another facet of Amerindian leadership in Darién. Tule leaders were numerous, and they were also fiercely independent. Though they considered themselves to be one people and assisted each other when faced by dire threats, as leaders they owed one another neither automatic allegiance nor obeisance. | |

|

During his visit Pedro quarreled bitterly with Corbette. Long surmised that this most recent visitor was jealous of Corbette because of the commission the latter held from Louis XIV. However, Long casually mentioned what might have been an even more likely reason for the enmity between the two men: "Monsieur Du Cass the French governor upon Hispaniola had sent to [Corbette] to receive three or four friars into the country and [Pedro thought] that [Corbette] was a fool and did not mind it," 61 that is, in not opposing the friars. According to Long, in times of peace with the Indians the Spaniards were wont to send friars among them "which the Indians … used to kill upon some disgust or another." 62 | |

|

Long was creating a deep and detailed narrative for his readers at the Admiralty, and he organized the facts of his narrative to fit the poetics of its creation. He constructed a narrative in which competition with the French and their clients in the region ought to give impetus to English efforts in the Darién. Long was careful to highlight where he had modeled his actions on the French manner (he fired two guns to alert the Indians of his arrival, followed their pilots, etc.), and throughout the account he depicted himself as having entered into a geopolitical system already thoroughly penetrated by Frenchmen and their clients. Long implied, though he never explicitly said, that the peace recently made between the two formerly warring Indian nations was the handiwork of the French. The Englishman learned of the entente from the band of Frenchmen he encountered at Port Moranto. Long reported that, as was the case in Europe, the prevailing geopolitical winds in the Darién blew with a threatening Gallic edge. | |

|

Long, perceiving that the Indian chieftain and his French companion were fearful of him, worried that Captain Pedro would leave him the next day. Unsure of his newfound friends, Long resolved to seek out Ambrosio in his own territory, which was six or so miles inland. On arriving, Long found that Ambrosio was not at home. However, the Englishman did find that there "lived a Spanish Negro who was slave to [Ambrosio, and that] … this Negro was a very sensible man." 63 Long learned from him that Ambrosio was searching for gold, though not digging for it in some mine, as Long had thought, but rather prospecting for it after the Indian fashion, searching along the riverbeds after the rains. | 45 |

|

On October 18, after dinner, Ambrosio and many more Indians appeared armed "and three Indians of the Gulf with them one of which was son to Diego the Indian governor of the Gulf." 64 This man carried a box of gold dust as a gift for Ambrosio, to make firm the rumored peace between the groups. Long was introduced to Ambrosio, and the chieftain "being informed who I was and that I had been kind to the Indians … came and took me in his arms and told me I was as welcome to his country as any Frenchman." 65 This rhetorical flourish did not sit well with Captain Pedro’s French companion, Sylvester. After Long slyly misinformed Ambrosio that his intention was to sail for the Gulf of Urabá to search for pirates, Sylvester voiced opposition to Long’s request for an Indian pilot to guide him eastward. The Frenchman’s intrigues, however, were no match for an indigenous leader’s hospitality to a newly made friend. Long made it clear in his account that although he had established a working relationship with the most respected leader of the Indians in the western part of the isthmus, he had done so under the shadow of the French. His relationship with Ambrosio had been established in the "house [that] was the principal place of rendezvous for the Frenchmen … about 20 leagues westward in them parts was the best land for plantation." 66 Long gave Ambrosio several presents upon taking his leave, and the two men renewed their earlier promises of amity and friendship. | |

|

Setting sail to the east, Long anchored at the Isle of Pines, a spot he had visited in 1677. At this point in his account Long provides what he thinks to be tangible evidence of the success of his tropical rain forest diplomacy. "In July of 1677," he writes, "I could not send a boat ashore for fresh water nor to go fishing near the shore they so annoyed us with their arrows from behind the bushes." 67 Now, however, Ambrosio and his people seem to have spread the good word about Long, and curious Indian leaders amicably sought him out. Goans, a captain from the lands between the Isle of Pines and Golden Island, came aboard the Rupert and had a friendly meeting with Long. The upbeat mood of amity, however, was cut short, when Long spotted what he assumed to be one of the Spanish Barlovento squadron in the distance. The Englishman ordered his crew to be on their guard, and weighed anchor. | |

|

On October 28 Long finally arrived at the Gulf of Urabá, anchoring near a path which, he was informed by his native pilot, led to the home of the Indian governor. The pilot obligingly headed for the mountains toward the governor’s house to announce their arrival, promising to return as fast as he could. In the interim, a group of local Indians from the region of the Cacarica River boarded the Rupert and made a friendly visit. Long received them well, but grew impatient with waiting for the pilot to return. He decided impetuously to set out to find the governor’s house, accompanied by his surgeon, his corporal, and a Negro, all unarmed. The party arrived at the house at nightfall, finding a large structure "which had port-holes and served for a garrison for about 150 men." 68 | |

|

Inside the "garrison" Long found Diego, the Indian governor of the Gulf of Urabá. Diego spoke some Spanish, and was, upon Long’s arrival, sitting alone in his pavilion, regally holding in his hand a long black staff and wearing a black cap. Long claimed to understand Diego well, but this was pushing the limits of the truth, for he then went on to relate that the Indian chieftain "agreed with me that the King of England should enjoy and have the Gulf of Darién and river running into it and the countries thereto adjoining, earnestly desiring that they might be inhabited by English who might intermarry with them." 69 Diego supposedly went so far as to tell Long that he would arrange for his people to plant crops that the English settlers would like, so that the English would have food waiting for them when they arrived. | |

|

It is doubtful that Diego would have expressed desires so in accord with Long’s own plans. Clearly the Indian treated Richard Long civilly, exchanged food and gifts with him, and obviously did not object to Englishmen settling in the Darién. However, Long could honestly report that he had dealt successfully with all of the Tule Indians he had found on the Caribbean coast of the isthmus, and remarked that he appeared to be driving a large wedge between the problematic conjunction of French pirates and Tule Indians that had taken hold without any previous visitor’s notice. | 50 |

|

Immediately after leaving Governor Diego, Long returned to the Isle of Pines, arriving there on November 12. Any joy Long may have felt on the success of his expedition was to be short-lived, however. Long believed himself to be engaged in a strategic battle for the alliance of the Tule Indians waged between the French and the English, but he gradually found himself instead confronted by the harsh reality of the Scots settlement on the Darién coast. He found that Ambrosio was on his way "then to visit the Scotch … not expecting to meet me there…. My man that he brought with him told me the first news that I had heard of the Scotch: at which I was … surprised." 70 The great ship Long had spied more than a week earlier was not a member of the Spanish Barlovento fleet at all, but rather one of the Scottish flotilla. | |

|

The Scots fleet, consisting of the Caledonia, the St. Andrew, the Unicorn, the Endeavor, and the Dolphin, had set sail from Leith on July 26, 1698, reportedly cheered by a multitude offering them their tears, prayers, and praises. 71 The commodore of the fleet was Captain Robert Pennycook. 72 He commanded not only the Scottish ships and the mariners manning them; while the Scots were at sail he held also held responsibility for the 1,200 souls who had signed on to settle Darién. The affairs of the colony had been entrusted to a council consisting of seven men, four of whom were captains of the ships of the fleet. As commodore and leader of the majority sea contingent on the council, Pennycook considered himself the chief Scottish councilor and subsequently dominated the first encounters with Darién’s Tule Indians. 73 | |

|

The Scottish ships arrived in the Americas on September 28, and on October 2 Commodore Pennycook ordered the Unicorn, Captain Pincarton commanding, to sail for St. Thomas and pick up any Danish pilots willing to lead them to Golden Island "and [to get] what intelligence was possible of the state of Darién." 74 The Unicorn returned on October 5 "and brought one Allison along with them, who freely offered to go along with us to Golden Island. This man is one of the eldest privateers now alive. He commanded a small ship with Captain Sharp … [and] had likewise been at the taking of Panamá, Portobello, Chagres, and Cartagena." 75 | |

|

On the night of October 27 the St. Andrew anchored "in a fair sandy bay about three leagues westward of the Gulf of Darién" and was visited by two canoes with several Indians in them. Pennycook reported in his diary that these men were given food and drink, "which they used very freely, especially the last." 76 These Indians spoke some words of English, and they spoke Spanish indifferently. In questioning the men, the Scottish commodore was able to gather that Tule medicine men had prophesied the Scots’ arrival some two years ago, and that consequently the settlers were welcome. | |

|

Pennycook set his ship toward Carret Bay, the site of the ancient town of Acla, in the region the Spaniards knew as Rancho Viejo. In spite of Allison’s assistance, the Commodore was unable to find anchor at Golden Island, and it was not until November 1 that he and some others went out in longboats to sound the island, which they found inadequate for either settlement or defense. Upon the completion of this operation, they came upon a group of Tule Indians, all armed with bows and arrows and lances, "but upon our approach," Pennycook wrote, "they unstringed their bows in token of friendship." 77 Pennycook had one of his men swim ashore to know their meaning, and it became clear that the Tule desired the Scots to make their way ashore. Pennycook did not assent to this request, keeping the bulk of the men aboard the ship. Unfazed by this caution on the part of the Scots, the Tule made it known that the Commodore’s ship would be visited by two great Indian captains the next day. | 55 |

|

The following day’s visit was recognized by all observers as one of the most important to the Scottish endeavor. Captain Andréas, 78 a Tule Indian of small stature, grave carriage, and wearing a coat of red stuff in the Spanish fashion, introduced himself to the commodore. For the Scots the introduction was the moment at which the one-dimensional images of Indians that they possessed could be challenged by an American reality. Outsiders and latecomers desiring to found a permanent settlement in America, the Scots needed desperately to find native Americans of a particular sociopolitical standing in relation to the Spanish. 79 It was imperative for them to encounter autonomous Indians, ruled by leaders of their own choosing, masters of the lands on which they lived. Captain Andréas caught the eye, for if such men could not be found they would need to be created: they were the linchpin to the tenuous Scottish claim to possess the Darién. | |

|

The recent activities of the buccaneers had proven that the Spaniards’ grip on the isthmus was at best a slack one. All observers granted that the central and western regions of the isthmus, first reconnoitered by Columbus, were firmly under Spanish jurisdiction. The region from the Bocas del Toro to Portobello-Panamá could be attacked, but it could never be held. However, the predations of the pirates, and the absence of Spanish population centers, indicated that the Spanish had never conquered Darién as they had conquered the Indian heartlands of Mexico and Peru. | |

|

The act incorporating the Scottish Company instructed the directors to seek trade and settlements in lands unclaimed by any other Christian prince or nation, and the propagandists at work for the Company ventured several arguments attempting to prove that, by all accounts, "the Dariens are in actual possession of their liberty, and were never subdued, nor received any Spanish government or garrison amongst them…. And [Bartolomé de Las Casas,] the Bishop of Chiapa[s] … in his Relation of the Spanish voyages and cruelties in the West Indies … owns ‘that the Spanish had no title to the Americas as their subjects, by right of inheritance, purchase, or conquest.’" 80 | |

|

Like a late-seventeenth-century Ralegh or Hernán Cortés, Pennycook carried himself as if he were the representative of an expanding European state, empowered to engage in negotiations with indigenous peoples who had had minimal (and entirely hostile) encounters with the Spaniards or any other European nation. In short, Pennycook acted as if he were a sixteenth-century colonizer. He was a Scottish Cortés, an imperialist with a difference. He had learned the many lessons of Spain’s imperial blunders. The commodore was on no small errand, for he intended nothing less than to bind Darién, a remote border region previously visited by pirates and the odd Spaniard, into regular and permanent intercourse with an advanced European state. Rather than a rapacious papist out for gold and plunder, the representative of an empire corrupt at its metropolitan core, he saw himself instead as the leader of a enterprise whose goal was to foster an empire of honest, open trade in the Americas. | |

|

Not subdued by the Spanish, the Darién Indians were conceived to be in full possession of their native lands, and in a position to treat with him in full freedom. As Moctezuma had transferred the sovereignty over his lands and people to Cortés nearly two hundred years before, effecting the only manner of secure and legally acceptable transfer of authority and possession the Spanish could claim, so the unconquered natives of Darién, when convinced of the benefits of such an action, would willingly transfer their powers of lordship and possession to the council of the Scottish colony. 81 | 60 |

|

Captain Andréas arrived aboard the commodore’s ship on November 2 accompanied by ten or a dozen of his people. Though amicable, the Indian wasted no time, immediately "inquir[ing] the reason of our coming hither and what we designed." The commodore responded by saying that their design was "to settle among them if they pleased to receive us as friends: that our business was chiefly trade, and that we would supply them from time to time with such commodities as they wanted, at much more reasonable rates than either the Spaniard or any others can do." 82 | |

|

Andréas must have been taken aback by Pennycook’s claim that the Scots’ business was trade. The Tule leader knew, if Pennycook did not, that for a non-Spaniard to do anything in this region, he had to be prepared to fight for the right to do it. Throughout the Americas there are many examples that make clear the terms under which Amerindians inhabiting the often war-torn borderland regions of the Spanish empire allowed settlers to trade and form settlements among them. For these precarious communities, caught in the crossfire between warring European empires and hostile indigenous groups, offers of amity to strangers were understood to produce reciprocal military assistance. 83 | |

|

Andréas’s next question confirms this line of analysis, for "[h]e inquired if we were friends to the Spaniards." 84 The response to this question must have been a disheartening one to the Amerindian leader, Pennycook responding "that we had no war with any nation; … if the Spaniard did offer us no affront or injury, we had nothing to say to them." Later in their interview, Andréas "began to run out in the praise of Captain Swan and Captain Davies, two English privateers, and whom he knew in the South Seas." Pennycook’s comment on this observation is the most telling of all, for in distancing himself from the buccaneers he recorded that he cut the Tule leader short, informing him bluntly that "we were on no such design." 85 | |

|

The next few days were to be eventful ones for the councilors of the Scottish settlement. On November 3, the day following their interview with Andréas, a scouting party discovered a great harbor that was "capable of containing a thousand sail of the best ships of the world." 86 Richard Long confirmed the Scots reports of having found an ideal site in which to settle, reporting that "the Scots are in such a crabbed hole, that it may be difficult to beat them out of [it]." 87 Later that day Andréas revisited the Scottish commodore, probably trying to set their relations on a firmer footing. Pennycook, unaware that anything could be amiss, was rather annoyed at the Indian’s persistence. He wrote testily that he found the man "still on the pump as to our designs." 88 | |

|

Andréas took this opportunity to raise the stakes in the diplomacy in which the two men were engaged, informing Pennycook that in the past English visitors to the region had, after claiming to be friends to his people, carried away Indian men who were never seen again. This problem was serious enough to have prevented Captain Pedro, who had an interest in visiting the Scots, from "ventur[ing] aboard till he were better assured of [their] integrity." 89 In parting, Andréas cunningly informed Pennycook that there were Frenchmen who had been living among the Indians for some time to the west of the Scottish settlement. | 65 |

|

On November 6, after the council decided where to build fortifications, "there arrived a canoe with a Frenchman, two Creoles of Martinique and four Indians, as also a [canoe] with Captain Ambrosio and Pedro who live sixteen leagues to the westward." 90 These Darién-dwelling Frenchmen, especially one man in particular, "the most sensible of them [who] speaks the [Indians’] language perfectly" provided the commodore with his most detailed information to date about the geopolitical situation on the isthmus. In one blow this communication dispelled all of the myths and wishful thinking about the Indians that Pennycook had harbored. The Frenchman made it known to the Scots "that the stories of an Emperor or King … were mere fables." 91 The hope of finding a single individual who could cede the entire territory to the council was dashed. Instead of enjoying a sixteenth-century transfer of sovereignty, the Scots found themselves thrust into a seventeenth-century contest for indigenous alliances. | |

|

Pennycook’s French informant, however, bettered the odds for the Scots, allowing the commodore to learn quickly what only practical experience had delivered to Captain Richard Long. The Frenchman provided a detailed description of the various polities to be found throughout Darién, from the Bocas del Toro region in the west through the Pacific coast of Darién in the east. The freedom with which the French ex-pirates shared information with the Scots intruders illustrates that these men considered themselves stateless figures, and not agents of the French government. 92 In any event, to act as representatives of Louis XIV would have been counterproductive, because the situation in Europe portended nothing but continuing hostility between Louis XIV and William of Orange. For men thinking at the local level, a Scottish or English colony in Darién, rather than pose a threat to their existence, would provide a larger and more visible target on which the Spanish could concentrate their efforts. If successful, the colony would offer the Frenchmen not only trading partners but also possible allies and protectors with whom to confront the Spanish forces in the region. | |

|

A week later the paths of the two expeditions, the larger Scottish settlement, and the smaller scale effort of Richard Long, crossed notably. On November 13 Pennycook reported in his diary that "we saw a ship standing to the westward which we believed to be Captain Long in the Rupert Prize, who we heard was in the Gulf of Urabá. On November 15 Captain Long came in his boat to visit us, and on the day after dined aboard of me. We could by no means find him the conjurer he gives himself for." 93 Richard Long described in his own account that on November 14 he and the Tule chieftain Ambrosio visited the Scots, the Indian "in his [canoe] … and I accompanied him in my longboat wearing His Majesty’s colors." To his surprise, Long "perceived that the Scots took no more notice of Ambrosio than of any other Indian, not having seen him before nor knowing what he was until I made them sensible thereof." 94 After introducing Ambrosio to the Scottish councilors, Long spent several days in the company of the Scottish ships. Observing their frequent meetings with the local Indians, however, Long decided he had better get on with his own business, and set a course for the Gulf of Darién. The Scots had yet to reconnoiter in that part of the isthmus, and Long intended to prevent them from ever laying claim to the easternmost stretches of Darién. | |

|

No reports gave the details of the first meeting of Pennycook and Ambrosio, though it is clear that the Indian made a great impression. On November 17, the commodore ordered that he and three other councilors should "go in two long boats and two pinnaces … as far as Ambrosio’s … to survey the coast and know whether there might be any more convenient place for a settlement." 95 Pennycook makes no mention of the reason for this decision, but Ambrosio’s presence among the councilors on the days before it was made leads to the conclusion that the Tule leader made a strong case to the Scots that they would be better off living in his domain, and that Andréas was not to be trusted. | |

|

Ambrosio and his son-in-law Pedro received the Scots well, and to their surprise the visitors found a great harbor in Ambrosio’s country. In the end, and for reasons not stated in any official account, the councilors decided to remain in the site near Carret Bay where they had docked their ships in late October. Although they were committed to keeping their settlement in Andréas’s domain, the visit to Ambrosio had clearly raised grave suspicions in the councilors’ minds regarding Andréas. While dining aboard the commodore’s ship on November 30, the councilors decided to place their doubts concerning Andréas on the table. It being St. Andrew’s day, "Captain Andréas was … invited, the Council wanting an opportunity of clearing some suspicions they had of his correspondence with the Spaniards; we taxed him home with it and he ingeniously confessed that the Spaniards had been friendly to him, and had made him a captain; that he was obliged for his safety to keep fair with them." 96 | 70 |

|

The Scots pledged to Andréas that they intended to found a permanent settlement and were not simply pirates intending to pull up stakes, as he had been told by the Spanish. In turn, the Tule leader pledged himself amenable to sponsoring the settlement, and asked to be taken under the Scottish protection and government. He promised to return in a few days, when their relationship could be appropriately solemnized. | |

|

On December 4 Andréas boarded the St. Andrew, and his commission was read to him. Tellingly, the text had to be expounded in Spanish for the Tule leader to understand its provisions fully. "The council made him to be one of their captains to command the natives in and about his own territories, and received him into the protection of their government, he being obliged … to obey, assist, and defend them with all … concerns upon all occasions." 97 Pennycook reported that Andréas was very well satisfied with this arrangement, and that he promised to "defend us to the last drop of his blood against our enemies." 98 The Tule leader presented the council with a bow and bunch of arrows, and then he and those with him drank heartily to the health of the colony and its councilors. | |

|

Pennycook’s diary paints an entirely positive picture of his encounter with the Tule leader. The commodore, forced by the information he gained from the Frenchman’s report, downgraded the nature of Andréas’s cession to him. The act was described as the exchange of the deed to the lands surrounding the settlement, rather than an imperial ceding of sovereign lands. Although he might not have been ceded all of the Darién, Pennycook made clear that the parcel of land he did get had been won through strict adherence to appropriate diplomatic protocol. The commodore created a narrative of Scottish reasonableness, good sense, and open-handedness that convinced and won over the Amerindian leader. | |

|

The "Andréas" of Pennycook’s diary agreed, upon being presented the Scottish case in full, not only to abjure his relationship with the Spanish, but also to defend the Scots and their settlement with his life. Furthermore, he explicitly accepted that his right to rule was now conditional upon the Scots. "Andréas" had done nothing less than accede to his demotion from an autonomous regional lord to a delegate-ruler acting according to the pleasure of the colony’s council. A Scottish commission was now the only thing that allowed the diary’s "Andréas" to command the natives in and about his own territories. | |

|

Yet, clearly, Andréas had not assented to such an agreement. What he had more sensibly done was to appear to meet the needs of the commodore in order to keep open the avenues of communication and reciprocal interaction with the representative of a populous new settlement in his territory. This was the manner in which indigenous leaders throughout the Americas built alliances with European outsiders. Trust and allegiance could not be finalized through testimonies recorded for all time on paper. These relationships, and the benefits of trade and defense that they brought, were girded by myriad reciprocal exchanges and interconnections that took time to develop. Once in place, however, such connections could never be taken for granted. The exchanges that formed their base needed to be continually reenacted, and alliances, therefore, continually needed to be renewed. | 75 |

|

A pamphlet published soon after the events in question paints a picture at variance with Pennycook’s description of his encounter with Captain Andréas. The author, Walter Harris, was an eyewitness to the events described by Pennycook, and provided details absent from the Commodore’s diary. 99 Harris described Andréas’s government as extending from Carret Bay, about eight or nine miles on one side of the settlement, to Golden Island, about five miles on the other side. He added sarcastically that "such a portion of land [was] the lairdship or kingdom of these captains whom the buccaneers, privateers, and Scotch company would have be kings and sovereign princes." 100 | |

|

Harris, a member of the party that left to seek a better settlement site closer to Ambrosio, filled in some of the gaps in Pennycook’s account. It was Ambrosio himself who had seeded the minds of the Councilors with doubts against his rival, Andréas, informing the Scots councilors that Andréas was not only a Spanish captain, "but a very Spaniard in his heart." 101 Lobbying for the protection an alliance with the Scots would bring, on a subsequent visit to the councilors Ambrosio endeavored to persuade the Scots "to remove from that place and come nearer to him." 102 The councilors, as we have seen, actually considered this request seriously. However, after inspecting the harbors and grounds nearest to Ambrosio’s home, they decided that the fort at the original settlement was the most secure one, and they resolved to "make the best bargain with Andréas we could." 103 | |

|

Harris’s description of Scottish relations with Andréas differed from Pennycook’s in two other ways. First of all, Harris alleged that Andréas left the commission granted him behind on the St. Andrew when he left the ship on December 3, "which [Harris] found the day following crammed into a locker of the roundhouse where the empty bottles lay. Next time [Andréas] came aboard it was given him." 104 This observation illustrated, Harris hoped, the lightness with which Andréas took his new responsibilities and the low value he placed on his arrangement with the Scots. Harris’s second assertion is an even more serious one, and one that, again, was not disputed by other controversialists as a point of fact. 105 | |

|

Harris also wrote that "Ambrosio was with us during the Christmas holidays, and having met Captain Andréas … reproached him with his villainy." The two indigenous leaders came to blows in their dispute and were separated by Commodore Pennycook. Harris then remarks that "a bowl was made and the friendship made up, they seemed to be good friends all that night, till about the time that they were to go to sleep. Poor Captain Andréas either fell or was rumbled down the main hatchway into the hold, where lighting on a spare anchor … he was so bruised that he gave up the ghost soon afterwards…. His brother-in-law Captain Pedro, with the interest or advice of the Senate, was seated on his throne." 106 | |

|

There is no mention of Andréas’s death in Pennycook’s diary. Tacit confirmation of the Tule leader’s death, however, can be inferred from his abrupt disappearance from the commodore’s account. Following the end of 1698, Captain Pedro is the Indian leader with whom the councilors exclusively interacted. | 80 |

|

Commodore Pennycook’s complete silence regarding the dramatic death of Andréas is more than an example of an imperious racialist failing to report events of impact and importance to the mother country simply because their consequences would be felt only in the indigenous world. Rather, the Scotsman’s calculated silence on the matter was the attempt, by a man answerable to a board of directors, to conceal an unsavory episode in his management of Scottish relationships with the Tule Indians, whom he had been urged to cultivate as allies and friends. | |

|

After noting the progress the Scots were making with the region’s Indians, Richard Long had decided that he had better leave them and cement the understanding he had made with Diego, the Tule Governor of the Gulf of Urabá. Long feared that the Scots would make an agreement with Diego and claim all of the Darién for themselves, and he also suspected that news of the Scottish settlement would provoke other nations to grab pieces of the isthmus. On November 25 Long arrived at the Gulf of Urabá and was visited by the governor, who came down to the shore with about forty Indians. | |

|

Long took great pains to explain to the Tule leader that although the Scots and English spoke the same language and were even ruled by the same king, they had rival interests in the Darién. The Englishman admonished Diego that he should under no circumstances allow the Scots to settle on his lands, warning the Indian that the Scots would be visiting him soon with such a design in mind. Long ended the negotiations by telling Diego that he had returned to the Gulf "to leave some of my people with him to stay until some more should be sent thither from the King of England." 107 The governor’s reaction to this news was positive, with Long noting that "[Diego] and the rest seemed to be as joyful at the news thereof as I ever saw anybody in my life." 108 | |

|

Although it may have appeared otherwise to Long, this positive reaction on the part of the Tule leader, rather than reflecting a desire among the Indians to become English subjects, was instead a sign of the hope that the English would show themselves to be reliable allies and providers of military assistance. The Tule under Diego occupied the exposed eastern frontier of Darién that was continuously harassed by Indian allies of the Spanish residing on the other side of the Gulf. Tellingly, during the discussion the Tule were interested in knowing how many muskets Long had to give them, whereas Long was interested in getting to work to clear the sites that Diego had allotted for homes to be built for the Englishmen. | |

|

On December 3 Long ended his expedition to Darién and sailed for Jamaica, having left behind the king’s colors, along with several of his men. 109 Because his commission had not empowered him to sign formal treaties or contracts with any Indians, he had not done so, but in spite of this Long was certain that he done the next best thing. He had laid an effective claim to the Gulf of Urabá, and with it he had gained access to the Atrato river for the English crown. Long believed that the formal acts of possession that he had performed at the Gulf, in conjunction with the diplomatic understanding he had achieved with Diego, the region’s indigenous leader, had guaranteed the strategic Atrato river for England. | 85 |

|

Of course, Diego had made no commitment to become an English subject during that conversation he and Long had shared on the shore of Darién. Long’s Raleghan vision had blinded him to the possibility that perhaps Diego might be motivated to seek a better alliance. On February 24, in a shrewd act that Long would probably ascribe to Scottish treachery, Diego signed a Treaty of Friendship, Union, and Perpetual Confederation with the representatives of the Scottish colony. The document not only symbolizes Long’s own misguidedness, but it also serves to discredit the failed imperial ideology shared by Britons in this period. Most of all, however, Diego’s Scottish treaty is a lasting testament to the practical manner in which Tule leaders kept their options open as they negotiated the volatile geopolitical situation that reigned in the isthmus of Darién. | |

|